Superhero

|

|

A superhero is a fictional character who is noted for feats of courage and nobility and who usually has a colorful name and costume and abilities beyond those of normal human beings. Since the definitive superhero, Superman, debuted in 1938, the stories of superheroes - ranging from brief episodic adventures to continuing years-long sagas - have become an entire genre of fiction, one that has dominated American comic books and crossed over into other media.

| Contents |

Common superhero traits

BatmanComicIssue1,1940.gif

There are a range of attributes that are commonly part of a superhero's make up, although they are by no means definitive (see Divergent character examples). Most superheroes have a few of the following features:

- Extraordinary powers and abilities, mastery of relevant skills, and/or advanced equipment. Although superhero powers vary, the ability to fly, superhuman strength, superhuman agility, and enhanced versions of any of the five senses are common superpowers. Many superheroes, such as Batman and The Green Hornet, possess no superpowers but have mastered skills such as martial arts and forensic sciences. Others have access to advanced equipment that imitates superpowers such as Iron Man's various suits of powered armor or Green Lantern's power ring.

- A willingness to risk one's own safety in the service of good, without expectation of reward.

- A special motivation, such as revenge (e.g. The Punisher), a sense of responsibility (e.g. Spider-Man), a formal calling (e.g. Green Lantern), or childhood emotional trauma (e.g. Batman).

- A moral code that is more advanced and strict than that of most people and a tendency to take personal lapses to it very hard.

- A secret identity

- A flamboyant and distinctive costume that usually hides the secret identity. It often has a symbol, such as a stylized letter or visual icon, on the chest. Costumes often reflect the superhero's name and theme, for example Batman resembles a large bat and the design of Captain America's costume echoes that of the American flag.

- An arch enemy and/or a collection of regular enemies that s/he fights repeatedly.

- Is either independently wealthy (eg. Batman) or has an occupation that allows for minimal supervision so their whereabouts do not have to be strictly accounted for (e.g. Superman's civilian job as a reporter or Spider-Man's job as a photojournalist).

- A secret headquarters or base

- A backstory, called an "origin story," which explains the circumstances of the character acquiring his/her abilities, as well as his/her motivation for fighting evil.

Fantastic_four_by_jack_kirby.JPG

Although most superheroes usually work independently, many also work in teams. Some, such as The Fantastic Four and X-Men, have common origins and usually operate as a group. Others, such as the Justice League and The Avengers, are "all-star" groups consisting of heroes of separate origins who also operate individually. Many superheroes, especially those introduced in the 1940s, work with a child or teen sidekick (e.g. Batman and Robin). This has become less common since the Silver Age, as more sophisticated writing and older audiences have lessened the need for special characters for the reader to identify with, and made such obvious child endangerment seem less plausible.

Superheroes most often appear in comic books, and superhero stories are the dominant genre of American comic books to the point that "superhero" and "comic book character" are often used synonymously. Superheroes have also been featured in comic strips, radio serials, prose novels, TV series, movies, and other media. Most of the superheroes that appear in these other media are adapted from comic books, but there are exceptions.

Marvel Comics Group and DC Comics, Inc. share ownership of the United States trademark for the phrase "Super Heroes" as it applies to comics, and almost all of the world's most famous superheroes are owned by these two American companies. For example, DC owns Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, and Marvel owns Spider-Man, Captain America, and the X-Men. However, throughout comic book history, there have been significant superheroes owned by others, such as Captain Marvel, owned by Fawcett Comics (but later acquired by DC) and Spawn owned by creator Todd McFarlane.

Gatchaman_screen_capture.JPG

Superheroes are largely an American creation, but there have been successful superheroes in other countries, most of which share many of the conventions of the American model. The most notable examples include Cybersix from Argentina, Marvelman from the United Kingdom, and Japanese tokusatsu series like Ultraman and Kamen Rider as well as anime and manga series like Science Ninja Team Gatchaman and Sailor Moon.

Although superhero fiction is considered a subgenre of fantasy/science-fiction, it crosses into many other genres. Many superhero franchises contain aspects of crime fiction (Batman, Daredevil), others horror fiction (Spawn, Hellboy) and many are similar to "hard" science fiction (X-Men, Green Lantern).

But because the fantastic nature of the superhero milieu allows almost anything to happen, some superhero series cross over into a variety of vastly different genres. For example, in the 1980s series, The New Teen Titans, the Titans faced off against a super villain who controlled a cult in one story, then went off to another galaxy to participate in a space war in the following story, then returned to Earth and became involved in a gritty urban crime drama involving young runaways. The content of each of these stories is quite different, yet the same principle characters are involved throughout the series.

Character subtypes

In superhero role-playing games (particularly Champions), superheroes are informally organized into categories based on their skills and abilities:

- "Brick": A character with a superhuman degree of strength and endurance and usually an oversized, muscular body, named after the rocky shape of The Thing, e.g. The Incredible Hulk, Colossus, Beast.

- "Blaster": A hero whose main power is a distance attack, e.g. Cyclops, Havok, Starfire.

- "Archer": A subvariant of this type who uses bow and arrow-like weapons that have a variety of specialized functions like explosives, glue, nets, rotary drill, etc., e.g. Green Arrow, Hawkeye.

- "Mage": A subvariant of this type that is trained in the use of magic, which partially or wholly involves ranged attacks., e.g. Doctor Strange, Doctor Fate

- "Martial Artist": A hero whose physical abilities are mostly human rather than superhuman, but whose combat skills are phenomenal, e.g. Daredevil, Captain America.

- "Super normal": A hero with no innate supernatural power whose abilities are due to training, determination, and natural talent alone, e.g. Batman, Robin.

- "Gadgeteer": A hero who invents special equipment that often imitates superpowers and who has the technical skills to use it to his or her best advantage, e.g. Forge, Nite Owl

- "Armored Hero": A gadgeteer whose powers are derived from a suit of powered armor, e.g. Iron Man, Steel

- "Dominus": A hero that uses a Giant Robot to combat villains, e.g. Roger Smith of Big O, Super Sentai (the Power Rangers)

- "Speedster": A hero possessing superhuman speed and reflexes, e.g. The Flash, Quicksilver.

- "Mentalist": A hero whose main abilities are psionic in nature such as telekinesis, telepathy and extra-sensory perception, e.g. Professor X and Jean Grey of the X-Men, Saturn Girl of the Legion of Super-Heroes.

- "Shapechanger": A hero who can manipulate his/her own body to suit his/her needs such as stretching, e.g. Mister Fantastic, Plastic Man or disguise, e.g. Changeling, Ela Vista.

- "Substance oriented Bodychanger - A shapechanger who can change his/her body into the equivalent of a mass of a substance that can have variable density such as sand or water. e.g. Sand, Husk.

- "Sizechanger": A shapechanger who can alter his/her size, e.g. the Atom (shrinking only), Colossal Boy (growth only), Hank Pym (both).

These categories often overlap. For instance, Batman is a martial artist and a gadgeteer, and Superman is extremely strong and damage resistant like a brick and also has ranged attacks (heat vision, superbreath) like an energy blaster and can move quickly like a speedster.

Divergent character examples

Wolverine-limited-series-001.jpe

While the typical superhero is described above, many break the mold. For example:

- Wolverine of the X-Men has shown a willingness to kill and behave anti-socially. Wolverine belongs to an entire underclass of superhero anti-heroes who are grittier and more violent than classic superheroes, often putting members of the two groups at odds. Others include Rorschach, Daredevil, The Punisher, Green Arrow and, in some incarnations, Batman.

- Spider-Man has been portrayed as an every-man hero, often showing poor judgment and being overwhelmed by the responsibilities of both costumed crime fighting and civilian life. After Spider-Man became popular, superheroes generally became more human and troubled so whether or not this makes Spider-Man a divergent character is questionable.

- The Incredible Hulk is usually defined as a superhero, but he has little self-control and his actions have often either inadvertently or deliberately caused great destruction. As a result, he has been hunted by the military and by other superheroes.

- Luke Cage (AKA Power Man) and his partner, Iron Fist, operated a business called Heroes for Hire which charged a fee for their services, though it was occasionally waived in certain circumstances.

- Many superheroes have never had a secret identity, such as Wonder Woman (in her current version) and the members of The Fantastic Four. Others that once had a secret identity, like Steel or Captain America have later made their true identity public.

- Some superheroes have been created and employed by national governments to serve their interests and defend the nation. Examples include Captain America, who was outfitted by and worked for the United States Army during World War II, and Alpha Flight, a superhero team that was created and is usually run by the Canadian federal government.

- Spawn, The Demon and Ghost Rider are actual demons, who find themselves manipulated by circumstance to be allies for the forces of good. Hellboy, on the other hand, is a demon who is virtuous on his own accord.

- Alternatively, The Mighty Thor and Hercules are gods of ancient mythologies reinterpreted as superheroes. Wonder Woman, while not a goddess, is a member of the Amazon tribe of Greek mythology.

- Emma Frost, a member of the X-Men, was a supervillain for several years before she turned to the side of good. Other characters who have treaded the line between superhero and villain include Catwoman, Elektra, Rogue, Venom and Juggernaut.

- Superheros may hide their powers from the public at large whilst not adopting a superhero identity through way of a costume, examples include the television characters Clark Kent in Smallville, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and later incarnations of Starman.

In addition, some parodic super heroes have been introduced. While they keep some of the stereotypical attributes of "classical" super heroes, they introduce features that make them anti-heroes.

- Super Dupont is a super-hero with all the stereotypical supposed characteristics of the typical Frenchman (including a beret)

- Super Liar is a caricature of French president Jacques Chirac turning into a super hero to be able to lie more effectively.

History and evolution of the character type

Predecessors

The origins of superheroes can be found in several prior forms of fiction. Many of their traits are shared with protagonists of later Victorian literature, such as The Scarlet Pimpernel, Arthur Conan Doyle's detective Sherlock Holmes and H. Rider Haggard's adventurer Alan Quatermain. The penny dreadful and dime novel stories of Spring Heeled Jack, Buffalo Bill, Zorro and Tarzan also influenced superheroes. Pulp magazine crime fighters, such as Doc Savage, The Shadow and The Spider, were probably the most direct influence. By modern standards, characters like Doc Savage could well be considered superheroes in their own right, but the appearance of Superman is generally considered to be the point at which the superhero genre truly began.

Action1.JPG

The rise and fall of the Golden Age of comic books

In 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster introduced Superman in Action Comics #1. Although the character was preceded by the costumed crime fighter The Phantom, featured in comic strips, Superman is still considered the first superhero, introducing many of the conventions that have come to define the term including a secret identity, superhuman powers and a colorful costume including a symbol and cape. His name is also the source of the term "superhero."

DC Comics (which published under the names National and All-American at the time) received an overwhelming response to Superman and, in the months that followed, introduced Aquaman, Hawkman, The Flash, Green Lantern, Batman, his sidekick Robin, and Wonder Woman, the first female superhero and the only significant one for quite some time.

Whiz2.JPG

Although DC dominated the superhero market at this time, hundreds of superheroes were created by companies large and small. Marvel Comics, then called Timely, found success with the Human Torch and Sub-Mariner. Cartoonist Will Eisner's The Spirit, featured in a newspaper insert, was also a hit. Quality Comics also found its own niche with its own characters, most notably with the surreal humor of Jack Cole's Plastic Man. The era's most popular superhero, however, was Fawcett Comics' Captain Marvel, who even outsold Superman during the 1940s.

At this time, superheroes largely conformed to the model of lead characters in American popular fiction in the first half of the 20th century. Hence, the typical superhero was a white, middle to upper class, heterosexual, professional, young-to-middle-aged man.

During World War II, superheroes grew in popularity, surviving paper rationing and the loss of many of their creators to service in the armed forces. The need for simple tales of good triumphing over evil may explain the war-time popularity of superheroes. Publishers responded with stories in which superheroes battled the Axis Powers and the introduction of patriotically themed superheroes, most notably Marvel's Captain America.

After the war, superheroes lost popularity. Part of the reason was that the genre at that time was highly formulaic and the reading public began to tire of it outside of the major stars like Wonder Woman, Batman, Superman, and Plastic Man. This shift led to the rise of other genres, especially horror and crime. The lurid nature of this material sparked a moral crusade which blamed comic books for juvenile delinquency. The movement was spearheaded by Dr. Fredric Wertham who argued, among other things, that "deviant" sexual undertones ran rampant in superhero comics. In response, the comic book industry adopted the Comics Code, which allowed for only the tamest superhero stories as originally conceived.

The Silver Age and the beginning of ethnic and gender diversity

In 1956, DC Comics, under the editorship of Julius Schwartz, decided to see if the superhero genre in a modernized science fiction format could be viable. So a new version of The Flash was introduced which became an immediate success. This led the company to revive Hawkman, Green Lantern, and several others - usually with a more modern, science-fiction angle - and to launch the all-star team the Justice League of America.

AmazingFantasy15.jpg

Empowered by the return of the superhero at DC, Marvel Comics editor/writer Stan Lee and the artists/co-writers Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, and other illustrators launched a line of superhero comic books, beginning with The Fantastic Four in 1961, which stressed personal conflict and character development as much as action and adventure. This led to many superheroes that differed greatly from the standards created in the 1940s with considerably more dramatic potential. Some examples:

- The Thing, a member of The Fantastic Four, was a super strong, but monstrous creature with rock-like skin, whose appearance filled him with self pity.

- Spider-Man was a teenager who struggled to earn money and maintain his social life in addition to his costumed exploits.

- The Incredible Hulk shared a Jekyll/Hyde-like relationship with his alter ego and was driven by rage.

- The X-Men were "mutants" who gained their powers through genetic mutation and who were hated and feared by the society they sought to protect.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, superheroes of other racial groups began to appear in Marvel Comics, including Black Panther, monarch of a fictional African nation, Luke Cage, an African-American "hero-for-hire," and Shang Chi, an Asian martial arts hero. Comic book companies were in the early stages of cultural expansion and many of these characters played to specific stereotypes. For example, Cage often employed lingo similar to that of blaxploitation films and Asians were often portrayed as master martial artists.

Strong female characters also gained prominence, beginning in a low key manner with Julius Schwartz's comics having female supporting characters who were successful professionals, although Hawkgirl was largely the only new female superhero as a confident partner for Hawkman. In the early 1960s Marvel introduced The Fantastic Four's Invisible Girl and The X-Men's Marvel Girl as well as The Wasp, but these characters were physically weak and were portrayed primarily as romantic interests of other team members. The 1970s saw these characters become more confident and assertive and the introduction of popular new female heroes, such as Spider-Woman and Storm of the newly revived X-Men. Initially, some characters were preachy radical feminist stereotypes like Marvel's Ms. Marvel and DC's Power Girl until writers grew more accustomed with society's changing attitudes.

1980s "deconstruction" of the superhero and its aftereffects

By the early 1980s, Marvel Comics had introduced several popular anti-heroes including The Punisher, Wolverine and writer/artist Frank Miller's darker version of Daredevil. These characters were deeply troubled from within, tormented by experiences such as the mob-related slaughter of The Punisher's family, Wolverine's battle with mutant animal instincts and Daredevil's rough childhood and continual exposure to slum life.

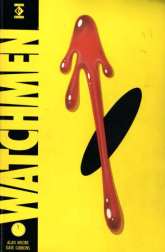

The trend was taken to a new extreme in the successful 1986 mini-series Watchmen by writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, which was published by DC, but took place outside the "DC Universe" with new characters. The superheroes of Watchmen were emotionally unsatisfied, psychologically withdrawn, and even sociopathic.

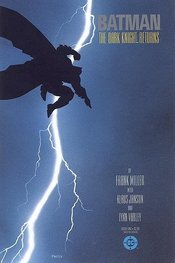

Another story, The Dark Knight Returns (1985-1986) adapted the trend to a familiar character. The mini-series, written and illustrated by Frank Miller, featured a future Batman returning from retirement. The series portrayed the hero as a madman who takes out his inner rage, drawn from the childhood murder of his parents, in a violent quest to mold society to his will.

Some critics believe that this trend is tied to the cynicism of the 1980s, when the idea of a person selflessly using his extraordinary abilities on a quest for good was no longer believable, but a person with a deep psychological impulse to destroy criminals was. Regardless, both series were heavily acclaimed for their artistic ambitiousness and psychological depth, and led to numerous imitations. Critic Geoff Klock associates the emergence of these anti-heroes specifically with Alan Moore and Frank Miller's examinations of a previously uniterrogated and fascistic will to order and moral certainty that informs the behaviour and actions of characters in the superhero tradition. As such, Moore and Miller's characters are as much pop philosophers as they are hero or anti-hero, and lack the 'a priori' ethical code and morally absolute motivations of their predecessors. But despite these complex literary conceits and deep psychological ambiguities, most artists following in the vein of "DKR" and "Watchmen" specifically emulated the visual style and ultra-violence of the texts without critically addressing their underlying politics and problematic behaviour.

By the early 1990s, anti-heroes had become the rule rather than the exception. Wolverine, The Punisher and Batman were joined by X-Force’s Cable, the X-Men’s Bishop, the Spider-Man adversary Venom, DC Comics’ Lobo and countless others.

Many critics complained these characters missed the essential artistic elements of redemption and tragedy of their inspirations, and were generic and psychologically paper-thin.

The struggles of the 1990s

In 1992, several former Marvel illustrators founded Image Comics, which featured creator-owned characters and became the biggest challenger ever to Marvel and DC's 30 years of co-dominance. Image introduced many popular, new heroes including Savage Dragon, Spawn and Witchblade and teams such as WildC.A.Ts, Gen 13 and The Authority. Many critics complained that the dominance of illustrators at Image made for superficial characters that, while sharing little with the long outdated 1940s model, were not overly complex or innovative and added to the glut of generic anti-heroes.

In 1990s, a counter-trend to that excess occurred where notable talents like Kurt Busiek and Moore, himself, tried to reconstruct the superhero genre with titles like Busiek's Astro City and Moore's Tom Strong that combined artistic sophistication and idealism into a superheroic version of retro-futurism. While nostalgia features prominently in both works, Busiek's title expresses an unambiguous form that yearns for a golden age in which superheroes are wholly altruistic and the world basically good, whereas Moore's title extends his superhero-as-fascist metaphor to encompass the contemporary 'retro' trend. Despite this, Moore is not entirely cynical about the superhero genre, leaving his own progressive take on superhero comics to the feminism-inspired Promethea and its invocation of the non-linear and anti-masculinist tradition of Écriture féminine.

Superman75.jpg

To keep ahead, Marvel and DC made drastic changes to beloved characters. The hugely successful "Death of Superman" found the hero killed and resurrected, a new villain broke Batman's back leading to a replacement Batman, and a clone of Spider-Man vied with Peter Parker for the title. While these stories drummed up publicity, often in the mainstream media, fans began to complain and lose interest. By the beginning of the 2000s, a majority of classic superheroes had returned to their roots.

By the 1990s, ethnic and gender diversity among superheroes was greater than ever before. Many characters in the X-Men, the most widely successful franchise of the time, were female, such as Storm and Rogue, or minorities, such as the Cajun Gambit and the African-American Bishop. There were also a few prominent gay superheroes, such as Alpha Flight's Northstar, Gen 13's Rainmaker and The Authority's gay couple Apollo and The Midnighter.

The genre's dominance in American comic books

The superhero genre has dominated American comic books for half a century. Before the 1960s, there were popular comics in many genres, including funny animal comics, westerns, romance, horror, war stories, and crime, with dozens of publishers small and large. This diversity disappeared rapidly in the 1950s, due to two factors.

The first was a series of highly publicized campaigns against "unwholesome" children's comics, leading to the establishment of the highly restrictive Comics Code Authority. Although the Code severely constrained superhero comics, it completely banned the grittier genres. This wiped out many small publishers, but left the large superhero companies intact.

Secondly, television drew away much of the audience for light entertainment in the late 1950s and early 1960s. By the time publishers moved away from the Comics Code and produced something other than light entertainment, television and movies were far more profitable. However, comics were still able to depict outlandish action-oriented adventures such as superhero tales without expensive special effects and in a higher volume than the movie industry.

Treatment in other media

Television

Animated series

Spiderman1967.jpg

With the rise of television in the 1960s, superheroes have found success in animated series geared towards children. The late-1960s saw the rise of Filmation's Superman-Batman Adventure Hour, and several attempts at series based on Marvel characters, the most successful of which was Grantray-Lawrence Animation's Spider-Man, featuring the "does whatever a spider can" theme song.

In 1970s Japan, there were anime attempts to emulate the American genre. By far the most successful was Kagaku ninja tai Gatchaman (Science Ninja Team Gatchaman) which produced 3 separate series. The series also established an action idiom of the five member team of specific builds and temperament which was emulated by the live action sentai genre.

In 1970s and 1980s American television broadcasting, superhero animated series were constrained by the broadcasting restrictions that activist groups like Action for Children's Television successfully lobbied for. The most popular series in this period, Super Friends, an adaptation of DC's Justice League of America was designed to be as nonviolent and inoffensive as possible. The Plastic Man Comedy/Adventure Show and Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends were similarly tame and Kagaku ninja tai Gatchaman was severely edited for violence in the translation called Battle of the Planets.

Starting with Batman: The Animated Series, which debuted on the Fox Network in 1992, superhero animated series gained a new maturity and respect for the comic books on which they were based. This continued with Fox's X-Men, and Spider-Man series as well as the original series Gargoyles, which, like Batman were geared towards older audiences but accessible to children.

The widely successful Batman: the Animated Series also had a significant influence on American animation. The show featured simple graphics but lavish animation, a style that was replicated in the sequel Batman Beyond, Static Shock and in Cartoon Network’s successful adaptations of DC's all-star Justice League and Teen Titans.

Live-Action series

Reevessuperman.JPG

While animated series found immediate success, live action series were often hampered by limited budgets and goofy writing. The 1950s The Adventures of Superman series starring George Reeves - an extension of the popular movie serials - featured very limited and unconvincing special effects. It was, however, hugely popular. Reeves made up for the lack of sophistication in special effects by injecting realism into the fight sequences, using his boxing skills.

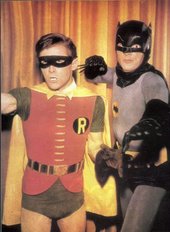

The live action Batman series of the late 1960s, starring Adam West and Burt Ward, was a ratings phenomenon. The psychedelically-colored series helped sell color televisions and introduced the characters to millions of viewers, but it was extremely campy and goofy and many comic book experts agree that it had a mostly negative effect on the public's perceptions of superheroes.

Batman led to imitators like Captain Nice and Mr. Terrific but only The Green Hornet starring Van Williams as the Hornet and a young Bruce Lee as his sidekick Kato approached the popularity of Batman.

Over in Japan, TV shows like Ultraman (1966) and Kamen Rider (1971) became the model superhero shows in Japan to this day, spawning countless sequels and imitations, few of which could match their successes. But unfortunately, because of rising standards against violence on American TV, only Ultraman (and a small handful of other shows) ever made it to the US, where they gained a niche following, compared to the wide audience in Japan and many other countries like Hawaii, Brazil, France, Italy and China (see tokusatsu).

By the late 1970s, superhero-ish series, such as The Six Million Dollar Man and its spin-off, The Bionic Woman, found limited success. This led to series which were explicitly superhero shows such as Wonder Woman starring Lynda Carter, which, like the previous decades’ Batman was a huge hit and continues to be a cult classic, despite an overhanging campiness. Children's programming frequently featured superhero characters, such as Shazam!, Isis, Electra Woman and Dyna Girl and Mighty Morphin Power Rangers (based on the Japanese Super Sentai series).

Ferrigno_as_Hulk.jpg

The Incredible Hulk series of the late 1970s, starring Bill Bixby as David Banner and Lou Ferrigno as the Hulk, took a more thoughtful and dramatic approach. The show focused on Banner’s nomadic lifestyle and the curse that being the Hulk had placed upon him. The series was a ratings success and has proven to be the most durable of this period.

The 1980s saw the launch of various live-action superhero series that did not have their origins in comic book lore, but only The Greatest American Hero, a series with a humorous yet respectful tone about a superhero who could barely control his powers, lasted for more than a few episodes.

In 1993, the ABC Network had a success with Lois and Clark, which reformatted the Superman mythos as a romantic drama. This led to several non-traditional approaches to superheroes in live action television shows, such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, featuring a dyed-in-the-wool idealist superhero who exists within a consciously humorous take on the horror genre. 1993 also brought Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, a TV show about five teenagers that were chosen to become superheroes. Based on the popular Super Sentai Series in Japan, Power Rangers, like Battle of the Planets, differed dramatically from its original Japanese counterparts (which were far more violent and had more challenging and complex stories).

Smallville has proven very successful in reinterpreting the characters of Clark Kent and Lex Luthor in their younger years, with a greater focus on their personalities, in a narrative format more familiar to the mainstream television audience. Other recent TV superhero or superhero-ish series enjoying varying degrees of success include: Angel, Alias, Roswell, Dark Angel, and Mutant X.

Film

Adventures_of_captain_marvel.jpg

Almost immediately after superheroes rose to prominence in comic books, they were adapted into Saturday movie serials aimed at children, starting with 1941's The Adventures of Captain Marvel. Serials featuring The Phantom, Batman, Superman and Captain America followed. These films were successful despite their limited budgets, silly plotlines, dialogue, and primitive special effects.

Fleishersuperman.JPG

In late 1941, Superman became the first superhero to be depicted in animation, The Superman series of groundbreaking theatrical cartoons was produced by Fleischer/Famous Studios from 1941 to 1943, and featured the famous "It's a bird, it's a plane" introduction. In addition, the Superman-inspired Mighty Mouse was the flagship series of the Terrytoons company.

In the coming decades, the decline of Saturday serials and turmoil in the comic book industry put an end to superhero motion pictures, an exception being 1966's Batman, an outgrowth of the television series.

Sprmnmovie.jpg

1978's Superman, directed by Richard Donner, is considered the first, and often the best, modern superhero film. Almost a biopic of the character instead of an action movie, the film won praise for its state-of-the-art special effects, Christopher Reeve's sincere performance as Superman, and John Williams's majestic film score. Superman was an extraordinary success but its three sequels, produced throughout the 1980s, became increasingly silly and less lucrative. Nonetheless, the first two films' production values and respect for the source material influenced most later superhero films.

The 1989 film Batman, directed by Tim Burton, was the first attempt to create a superhero film with the darker mood of recent comic books. Fantastic set designs and acclaimed performances from Michael Keaton as Batman and Jack Nicholson as The Joker made the film a model for many later superhero movies. The Batman series continued throughout the 1990s, grossing millions and drawing several star actors, until the fourth film Batman and Robin (1997) became a huge critical and commercial failure. This film, along with unsuccessful movies based on DC's Steel, and Todd McFarlane's Spawn, made movie studios nervous about superhero movies.

Nonetheless, several movies based on Marvel characters began production in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The company had a minor success with 1998's Blade, but 2000's blockbuster X-Men opened the door once again to highly successful superhero movies and 2002's Spider-Man broke the record for money grossed in a film's opening five days. Sequels, such as 2003's X2: X-Men United and 2004's Spider-Man 2 have also been highly successful.

The X-Men and Spider-Man films led to a widespread revival, which included 2003's Daredevil, Hulk, and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and 2004's Punisher and Hellboy, all of which met with varying degrees of critical and commercial success.

Movie_the_incredibles_family_posing.jpg

There were also productions that created original superheroes for their own dramatic purposes. For instance, Unbreakable by M. Night Shyamalan is a dark tale about a man who learns from a mysterious comic book dealer that he is destined to be a superhero complete with superhuman strength, stamina and clairvoyance. Pixar's digitally-animated The Incredibles combined a more comedic, but affectionate, approach with commentary on the superhero genre and its long history.

As of 2005, anticipated superhero films include Batman Begins, a new Batman movie unrelated to any of the previous ones, a new Superman film by X-Men director Bryan Singer, and a handful of additional Marvel-based films, including Fantastic Four.

Prose

Popular superheroes have occasionally been adapted into prose fiction, starting with the 1942 novel Superman by George Lowther. Elliot S! Maggin also wrote two popular Superman novels, Last Son of Krypton and Miracle Monday, in the 1970s.

Juvenile novels featuring Batman, Spider-Man, the X-Men, and the Justice League, have also been published from time to time, often marketed in association with popular TV series.

George R.R. Martin’s Wild Cards novels, launched in 1987, were a non-comic book-based science fiction series that dealt with super-powered heroes.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Marvel and DC released novels based on important stories from their comics, such as The Death of Superman and the year-long Batman: No Man’s Land.

Additional examples of original superhero prose can be found in zines, including both fanfic and original content by amateur writers.

See also

- List of female superheroes

- List of Jewish superheroes

- List of superhero teams and groups

- List of DC Comics characters

- List of Marvel Comics characters

- Evil genius

- Top superhero (and supervillain) hide-outs and bases

- Category: Real-life Superheroes

- Category:Nedor Comics superheroes

External links

- The Great Net Book of Real Heroes (http://www.sysabend.org/champions/gnborh/)

- Guardians of the North! (http://www.collectionscanada.ca/superheroes) a virtual museum tour through the history of Canadian superheroes, hosted by the National Library and Archives of Canada.

- A site devoted to developing superhero fiction online (http://www.superherofiction.com)

- Japan Hero - A site devoted to Japanese superheroes, both tokusatsu and anime. (http://www.japanhero.com/)da:Superhelt

de:Superheld es:Superhéroe fr:Super-héros it:Supereroe nl:Superheld no:Superhelt pt:Super-herói