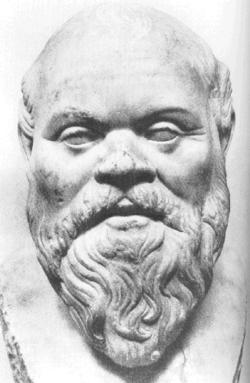

Socrates

|

|

Socrates (June 4, c.470 – May 7, 399 BC) (Greek Template:Polytonic Sōkrᴦamp;#275;s) was a Greek (Athenian) philosopher.

| Contents |

His life

According to accounts from antiquity, Socrates' father was Sophroniscus, a sculptor, and his mother Phaenarete, a midwife. He was married to Xanthippe, who bore him three sons. By the cultural standards of the time (and perhaps all time), she was considered a shrew. Socrates himself attested that he, having learned to live with Xanthippe, would be able to cope with any other human being, just as a horse trainer accustomed to wilder horses might be more competent than one not. Socrates enjoyed going to symposia, drink-talking sessions. He was a legendary drinker, remaining sober even after everyone else in the party had become senselessly drunk; this helped him obtain his reputation as a formidable conversationalist. He also saw military action, fighting at the Battle of Potidaea, the Battle of Delium and the Battle of Amphipolis. We know from Plato's Symposium that Socrates was decorated for bravery. In one instance he stayed with his wounded lover Alcibiades, and probably saved his life; despite the objections of Alcibiades, Socrates refused any sort of official recognition and instead encouraged the decoration of Alcibiades. During such campaigns, he also showed his extraordinary hardiness, walking without shoes and a coat in winter.

It is unknown what Socrates did for a living; in Plato's accounts he explicitly denies accepting money for teaching and does not seem to have any source of income, spending all his time engaged in conversation. However, it is unlikely that Socrates was able to live off of family inheritance, given his father's occupation as an artisan; in Xenophon's Symposium, Socrates explicitly states that he teaches for a living, paid by his students, and that he thinks this is the most important art or occupation. According to Aristophanes, he managed a scientific institute with his friend Chaerophon; Plato has Socrates tell us that he once spent all of his time on scientific research, but gave up on it when he came to see that it was philosophy that was truly important for study.

Socrates lived during the time of the transition from the height of the Athenian Empire to its decline after its defeat by Sparta and its allies in the Peloponnesian War. At a time when Athens was seeking to recover from humiliating defeat, the Athenian public court was induced by three leading public figures to try Socrates for impiety and for corrupting the youth of Athens. According to Dr Will Beldam he was the first person to question everything and everyone, and apparently it offended the leaders of this time. He was found guilty as charged, and sentenced to drink hemlock, which cost him his life.

According to the version of his defense speech presented in Plato's Apology, Socrates' life as the "gadfly" of Athens began when his friend Chaerephon asked the Oracle at Delphi if anyone was wiser than Socrates; the Oracle responded negatively. Socrates, denying that he knew anything, was unable to accept this and began to seek out the wise men of Athens, questioning them about their knowledge of good, beauty, and virtue; finding that they knew nothing yet believed they knew much led Socrates to the conclusion that he was wise only in so far as he knew he knew nothing and strived for knowledge. Historical accounts from varied sources, while questionable, suggest that Socrates had been studying philosophy for much longer than this and include Parmenides, Anaxagoras, Prodicus, the priestess Diotima and others as his teachers.

Socrates is probably the most influential thinker and philosopher of his time. Although no written accounts of his real life have been located, he is idolized by his disciples and thinkers that reflect on his accomplishments through their writing.

See Trial of Socrates for more detail and background about Socrates' trial and execution.

Quotes

Template:Wikiquote The following quotes are attributed to Socrates in Plato's and Xenophon's writings:

- The unexamined life is not worth living. (Apology, 38. In Greek, "ho de anexetastos bios ou bi? anthor?".)

- False words are not only evil in themselves, but they infect the soul with evil. (Phaedo, 91)

- So now, Athenian men, more than on my own behalf must I defend myself, as some may think, but on your behalf, so that you may not make a mistake concerning the gift of god by condemning me. For if you kill me, you will not easily find another such person at all, even if to say in a ludicrous way, attached on the city by the god, like on a large and well-bred horse, by its size and laziness both needing arousing by some gadfly; in this way the god seems to have fastened me on the city, some such one who arousing and persuading and reproaching each one of you I do not stop the whole day settling down all over. Thus such another will not easily come to you, men, but if you believe me, you will spare me; but perhaps you might possibly be offended, like the sleeping who are awakened, striking me, believing Anytus, you might easily kill, then the rest of your lives you might continue sleeping, unless the god caring for you should send you another. (Apology)

- Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius; will you remember to pay the debt? (Last words, according to the Phaedo — Asclepius was the god of medicine and healing, to whom such a sacrifice might be made upon the curing of a disease.)

- Really, Ischomachus, I am disposed to ask: "Does teaching consist in putting questions?" Indeed, the secret of your system has just this instant dawned upon me. I seem to see the principle in which you put your questions. You lead me through the field of my own knowledge, and then by pointing out analogies to what I know, persuade me that I really know some things which hitherto, as I believed, I had no knowledge of. (Oeconomicus by Xenophon, translated: The Economist by H.G. Dakyns)

See also

- Socrate, a symphonic drama by Erik Satie

Further reading and external links

Template:Commons link(s) for other Socrates information sources:

- [[1] (http://www.wsu.edu:8080/~dee/GREECE/SOCRATES.HTM)]

- Project Gutenberg e-texts on Socrates, amongst others:

- The Dialogues of Plato (http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/authrec?fk_authors=93) (see also Wikipedia articles on Dialogues by Plato)

- The writings of Xenophon (http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/authrec?fk_authors=543), such as the Memorablia and Hellenica.

- The satirical plays by Aristophanes (http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/authrec?fk_authors=965)

- Aristotle's writings (http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/authrec?fk_authors=2747)

- Voltaire's Socrates (http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/4683)

- The Second Story of Meno; a continuation of Socrates' dialogue with Meno in which the boy proves root 2 is irrational (by an anonymous author) (http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/254)

- An Introduction to Greek Philosophy, J. V. Luce, Thames & Hudson, NY, l992.

- Introduction to Philosophy, Jacques Maritain

- Greek Philosophers--Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, C. C. W. Taylor, R. M. Hare, and Jonathan Barnes, Oxford University Press, NY, 1998.

- Taylor, C. C. W. (2001). Socrates: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.