STS-51-L

|

|

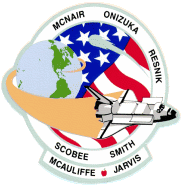

| Mission insignia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mission statistics | |

| Mission: | STS-51-L |

| Shuttle: | Challenger |

| Launch pad: | 39-B |

| Launch: | January 28, 1986 11:38 a.m. EST |

| Landing: | Scheduled for February 3, 1986 12:12 p.m. EST |

| Duration: | 73 seconds 6 d 34 min planned |

| Orbit altitude: | 150 nautical miles (280 km) planned, 8.7 statute miles (14 km) achieved |

| Orbit inclination: | 28.5 degrees planned |

| Orbits: | 96 planned |

| Distance traveled: | 18 miles (29 km) |

| Crew photo | |

| Missing image Challenger_flight_51-l_crew.jpg

Front row, left to right: | |

STS-51-L was the 25th launch of a Space Shuttle and the tenth launch of the Challenger. The vehicle exploded 73 seconds after launch on January 28, 1986 as a result of the failure of an O-ring seal in the right solid rocket booster (SRB): this caused a leak with a flame that caused another leak in the hydrogen tank. Among the crew was Christa McAuliffe, scheduled to be the first teacher in space. Students worldwide watched the shuttle launch and subsequent explosion on live television.

| Contents |

Crew

- Commander: Francis "Dick" Scobee (flew on STS-41-C & STS-51-L)

- Pilot: Michael J. Smith (flew on STS-51-L)

- Mission Specialist: Ronald McNair (flew on STS-41-B & STS-51-L)

- Mission Specialist: Ellison Onizuka (flew on STS-51-C & STS-51-L)

- Mission Specialist: Gregory Jarvis (flew on STS-51-L)

- Mission Specialist: Judith Resnik (flew on STS-41-D & STS-51-L)

- Payload Specialist: Christa Corrigan McAuliffe (flew on STS-51-L)

Mission parameters

- Mass:

- Orbiter Liftoff: 121,778 kg

- Orbiter Landing: 90,584 kg (planned)

- Payload: 21,937 kg

- Perigee: ~285 km (planned)

- Apogee: ~295 km (planned)

- Inclination: 28.45° (planned)

- Period: ~90.4 min (planned)

- Duration: 6 days 0 hours 34 minutes (planned)

Mission objectives

Planned objectives were deployment of Tracking Data Relay Satellite-2 (TDRS-2) and flying of Shuttle-Pointed Tool for Astronomy (SPARTAN-203)/Halley's Comet Experiment Deployable, a free-flying module designed to observe tail and coma of Halleys comet with two ultraviolet spectrometers and two cameras. Other payloads were Fluid Dynamics Experiment (FDE); Comet Halley Active Monitoring Program (CHAMP); Phase Partitioning Experiment (PPE); three Shuttle Student Involvement Program (SSIP) experiments; and set of lessons for Teacher in Space Project (TISP).

Launch

Challenger launched January 28, 1986, at 11:38:00 a.m. EST, the first Shuttle to launch from pad 39-B. Launch was originally set for 3:43 p.m. EST, Jan. 22; it slipped to Jan. 23, then Jan. 24, due to delays in mission STS-61-C. Launch was reset for Jan. 25 because of bad weather at transoceanic abort landing (TAL) site in Dakar, Senegal. To utilize Casablanca (not equipped for night landings) as alternate TAL site, T-zero moved to a morning liftoff time. Launch was postponed a day when launch processing was unable to meet the new morning liftoff time. A prediction of unacceptable weather at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) led managers to reschedule launch for 9:37 a.m. EST, Jan. 27. Launch was delayed 24 hours again when a ground servicing equipment hatch closing fixture could not be removed from the orbiter hatch. Maintenance crews sawed off and drilled out the attaching bolt before completing closeout. During the delay, cross winds exceeded return-to-launch-site limits at KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility. Launch Jan. 28 was delayed two hours when hardware interface module in the launch processing system, which monitors fire detection system, failed during liquid hydrogen tanking procedures.

Just after liftoff, at 0.678 seconds into the flight, photographic data show a large puff of gray smoke spurted from the vicinity of the aft field joint on the right Solid Rocket Booster (SRB). Computer graphic analysis of film from pad cameras indicated the initial smoke came from the 270- to 310-degree sector of the circumference of the aft field joint of the right SRB. This area of the SRB faces the Space Shuttle External Tank. The vaporized material streaming from the joint indicated there was incomplete sealing action within the joint.

Eight more distinctive puffs of increasingly blacker smoke were recorded between 0.836 and 2.500 seconds. The smoke appeared to puff upwards from the joint. While each smoke puff was being left behind by the upward flight of the Shuttle, the next fresh puff could be seen near the level of the joint. The multiple smoke puffs in this sequence occurred at about four times per second, approximating the frequency of the structural load dynamics and resultant joint flexing. As the Shuttle increased its upward velocity, it flew past the emerging and expanding smoke puffs. The last smoke was seen above the field joint at 2.733 seconds.

It was later determined that an O-ring seal in the right SRB had failed, losing pliability due to the cold weather. As the O-ring could not flex and expand, a gap opened in the SRB which could not be sealed by the O-ring, and superheated gases were able to escape for 2.5 seconds. The black color and dense composition of the smoke puffs suggest that the grease, joint insulation and rubber O-rings in the joint seal were being burned and eroded by the hot propellant gases. The gap was blocked by aluminium oxide particles generated by the burning fuel.

At approximately 37 seconds, Challenger encountered the first of several high-altitude wind shear conditions, which lasted until about 64 seconds. The wind shear created forces on the vehicle with relatively large fluctuations. These were immediately sensed and countered by the guidance, navigation and control system. The steering system (thrust vector control) of the SRBs responded to all commands and wind shear effects. The wind shear caused the steering system to be more active than on any previous flight.

Both the Shuttle main engines and the solid rockets operated at reduced thrust approaching and passing through the area of maximum dynamic pressure of 720 lbf/ft² (34 kPa). Main engines had been throttled up to 104 percent thrust and the SRBs were increasing their thrust. At this point, the aluminium oxide particles plugging the gap in the right SRB were jarred loose by the high winds, and the first flicker of flame appeared on the right SRB in the area of the aft field joint. This first very small flame was detected on image-enhanced film at 58.788 seconds into the flight. It appeared to originate at about 305 degrees around the booster circumference at or near the aft field joint.

One film frame later from the same camera, the flame was visible without image enhancement. It grew into a continuous, well-defined plume at 59.262 seconds. At about the same time (60 seconds), telemetry showed a pressure differential between the chamber pressures in the right and left boosters. The right booster chamber pressure was lower, confirming the growing leak in the area of the field joint.

As the flame plume increased in size, it was deflected rearward by the aerodynamic slipstream and circumferentially by the protruding structure of the upper ring attaching the booster to the External Tank. These deflections directed the flame plume onto the surface of the External Tank. This sequence of flame spreading is confirmed by analysis of the recovered wreckage. The growing flame also impinged on the strut attaching the Solid Rocket Booster to the External Tank.

STS-51-L-T_73.jpg

The first visual indication that swirling flame from the right Solid Rocket Booster breached the External Tank was at 64.660 seconds when there was an abrupt change in the shape and color of the plume. This indicated that hydrogen was now leaking from the External Fuel Tank (due to the flame) and was mixing with it. Telemetered changes in the hydrogen tank pressurization confirmed the leak. Within 45 milliseconds of the breach of the External Tank, a bright sustained glow developed on the black-tiled underside of the Challenger between it and the External Tank.

Beginning at about 72 seconds, a series of events occurred extremely rapidly that terminated the flight. Telemetered data indicate a wide variety of flight system actions that support the visual evidence of the photos as the Shuttle struggled futilely against the forces that were destroying it.

At about 72.20 seconds the hydrogen tank was weakening and the lower strut linking the Solid Rocket Booster and the External Tank was severed or pulled away, permitting the right Solid Rocket Booster to rotate around the upper attachment strut. This rotation is indicated by divergent yaw and pitch rates between the left and right Solid Rocket Boosters.

At 73.124 seconds, a circumferential white vapor pattern was observed blooming from the side of the External Tank bottom dome. This was the beginning of the structural failure of hydrogen tank that culminated in the entire aft dome dropping away. This released massive amounts of liquid hydrogen from the tank and created a sudden forward thrust of about 2.8 million pounds force (12 MN), pushing the hydrogen tank upward into the intertank structure. At about the same time, the rotating right SRB impacted the intertank structure and the lower part of the liquid oxygen tank. These structures failed at 73.137 seconds as evidenced by the white vapors appearing in the intertank region.

Within milliseconds there was massive, almost explosive, burning of the hydrogen streaming from the failed tank bottom, and liquid oxygen breach in the area of the intertank.

At this point in its trajectory, while traveling at a Mach number of 1.92 at an altitude of 46,000 ft (14 km), the Challenger was totally enveloped in the explosive burn. The Challenger's reaction control system ruptured and a hypergolic burn of its propellants occurred as it exited the oxygen-hydrogen flames. The reddish brown colors of the hypergolic fuel burn are visible on the edge of the main fireball. The Orbiter, under severe aerodynamic loads, broke into several large sections which emerged from the fireball. Separate sections that can be identified on film include the main engine/tail section with the engines still burning, one wing of the Orbiter, and the forward fuselage trailing a mass of umbilical lines pulled loose from the payload bay.

The explosion 73 seconds after liftoff destroyed the vehicle. The still-burning SRBs, separated from the tank in the explosion, were destroyed with on-board explosives designed for this emergency purpose (the Range Safety System) by remote command from NASA.

The crew cabin, separated from the orbiter, survived the explosion intact and fell into the ocean. Recovered debris show that at least 3 of the astronauts survived long enough to turn on their Personal Egress Air Packs (PEAPS, designed for on-pad emergencies), and were likely alive (although at least some were probably unconscious due to lack of oxygen) at the time of final splashdown, which would have killed them all.[1] (http://www.aerospaceweb.org/question/investigations/q0122.shtml)

Orbiter launch weight was 268,829 lb (121,939 kg).

Landing

None. A landing at KSC was planned after a 6 day, 34 minute mission.

Expected mission highlights

On Flight Day 1, after arriving into orbit, the crew was to have two periods of scheduled high activity. First they were to check the readiness of the TDRS-B satellite prior to planned deployment. After lunch they were to deploy the satellite and its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster and to perform a series of separation maneuvers. The first sleep period was scheduled to be eight hours long starting about 18 hours after crew wakeup the morning of launch.

On Flight Day 2, the Comet Halley Active Monitoring Program (CHAMP) experiment was scheduled to begin. Also scheduled were the initial "teacher in space" (TISP) video taping and a firing of the orbital maneuvering engines (OMS) to place Challenger at the 152 mile (282 km) orbital altitude from which the Spartan would be deployed.

On Flight Day 3, the crew was to begin pre-deployment preparations on the Spartan and then the satellite was to be deployed using the remote manipulator system (RMS) robot arm. Then the flight crew was to slowly separate from Spartan by 90 mile (167 km).

On Flight Day 4, the Challenger was to begin closing on Spartan while Gregory B. Jarvis continued fluid dynamics experiments started on days two and three. Live telecasts were also planned to be conducted by Christa McAuliffe, giving lessons to her students from orbit.

On Flight Day 5, the crew was to rendezvous with Spartan and use the robot arm to capture the satellite and re-stow it in the payload bay.

On Flight Day 6, re-entry preparations were scheduled. This included flight control checks, test firing of maneuvering jets needed for reentry, and cabin stowage. A crew news conference was also scheduled following the lunch period.

On Flight Day 7, the day would have been spent preparing the Space Shuttle for deorbit and entry into the atmosphere. The Challenger was scheduled to land at the Kennedy Space Center 144 hours and 34 minutes after launch.

Investigation

After the investigation, a Presidential Commission created the Rogers Commission Report detailing NASA's failings. The investigation and corrective actions following the Challenger accident caused a 32-month hiatus in shuttle launches: the next mission was September 29, 1988, when Discovery set off on mission STS-26. Reforms to NASA procedures were enacted which attempted to preclude another occurrence of such an accident, and the Shuttle program would continue without serious incident until the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster on February 1, 2003.

Controversy

Since recovered debris show that at least three of the astronauts survived long enough to turn on their Personal Egress Air Packs (PEAPS, designed for on-pad emergencies) and were likely alive but unconscious until final splashdown, there has been a significant amount of debate and speculation over the survivability of the STS-51-L disaster.

The number of crew members surviving until sea impact has been one of the most strongly debated subjects in Internet newsgroups. The need for a reinforced cockpit section and some kind of an emergency rescue system (either in the form of detachable, parachute-equipped cabin as used by the F-111 fighter-bomber or individual ejection seats, similar to K-36DM devices mounted on the ex-Soviet Buran space shuttle) is often advocated by amateurs and space professionals alike.

Bill Kaysing, best known for his claims that the Apollo moon landings were faked, claimed in an interview [2] (http://nardwuar.com/vs/bill_kaysing/index.html) that NASA deliberately destroyed the Challenger, as Christa McAuliffe would not agree to say that you cannot see stars in space (presumably this "lie" was to back up the fact that there are no stars in "faked" photographs of astronauts on the Moon). This claim is generally not believed - Kaysing made the error of saying that McAuliffe was the only woman onboard Challenger.

At least three different texts, each one claiming to be the exact transcript of STS-51-L on-board voice communications, have appeared on the Internet. These purported transcripts describe the astronauts' last moments as a mixture of prayers and vocal struggle trying to save their vessel. However, NASA denies both the authenticity of these transcripts and the existence of any recordings after the 73 second point, when the breakup-induced power loss stopped the recorders. NASA has made available an official transcript [3] (http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/transcript.html), compiled from the various voice recorders onboard, and covering the period from 125 seconds before until 73 seconds after launch. The last recorded remark is by the mission's pilot, Michael Smith, who says, simply, "Uhoh."

Tribute

On the night of the disaster, United States President Ronald Reagan was supposed to give his State of the Union address. Instead, he postponed it for a week and gave a poignant national address from the Oval Office of the White House.[4] (http://www.reaganfoundation.org/reagan/speeches/speech.asp?spid=23) At its end, he made the following statement: We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and "slipped the surly bonds of earth" to "touch the face of God." This speech has been remembered as one of the greatest addresses of his presidency. Three days later, he and his wife, Nancy traveled to the LBJ Space Center for a memorial service to honor the astronauts.

Nichelle Nichols of Star Trek was involved in the NASA recruitment process of Astronauts during the late 1970s to the early 80s and helped recruit both Ronald McNair and Judith Resnik. When Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home was released it bore the dedication at the beginning, "The cast and crew of Star Trek wish to dedicate this film to the men and women of the spaceship Challenger whose courageous spirit shall live to the 23rd century and beyond....". One shuttlecraft from Star Trek: The Next Generation was named Onizuka, after Ellison Onizuka, one of the crew members of the Challenger.

Related articles

- Space science

- Space shuttle

- List of space shuttle missions

- List of human spaceflights chronologically

- Space Shuttle Columbia disaster

External links

- NASA Spacelink on STS 51-L (http://spacelink.msfc.nasa.gov/NASA.Projects/Human.Exploration.and.Development.of.Space/Human.Space.Flight/Shuttle/Shuttle.Missions/Flight.025.STS-51-L/.index.html)

- NASA mission overview (http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/51-l/mission-51-l.html)

- Additional information (http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/51-l/51-l-info.html)

- Video retrospective of accident and comparison to Columbia mishap. (http://www.chrisvalentines.com/sts107/intromtt.html)

- Timeline of the flight including radio transcripts (http://spaceflightnow.com/challenger/timeline/)

- Reagan's speech honoring the astronauts and the mission (http://www.reaganfoundation.org/reagan/speeches/speech.asp?spid=23)

- Appendix to the Rogers Commission Report on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident (http://www.ralentz.com/old/space/feynman-report.html) by Richard Feynman, an analysis of the management process and of failures in project communication.

| Previous Mission: STS-61-C |

Space Shuttle program | Next Mission: STS-26 |

References

- Richard Feynman. What Do You Care What Other People Think? ISBN 0586218556. Describes the inner workings of the Rogers Commission, the confusion and misjudgement that plagued NASA and the moment when the cause of the Challenger disaster was revealed.

- Vaughan, D. (1996) The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture and Deviance at NASA ISBN 0226851761