Space Shuttle Columbia disaster

|

|

STS-107 was a space shuttle mission by NASA using the Space Shuttle Columbia. Mission STS-107 was launched on January 16, 2003. The shuttle disintegrated over Texas during reentry into the Earth's atmosphere, with the loss of the entire seven member crew, on February 1, 2003. This was the second total loss of a Space Shuttle, the first being Challenger (see STS-51-L for details on that disaster).

| Contents |

Crew

- Commander: Rick D. Husband, a US Air Force colonel and mechanical engineer, who piloted a previous shuttle during the first docking with the International Space Station.

- Pilot: William C. McCool, a US Navy commander

- Payload Commander: Michael P. Anderson, a US Air Force lieutenant colonel and physicist who was in charge of the science mission.

- Payload Specialist: Ilan Ramon, a colonel in the Israeli Air Force and the first Israeli astronaut.

- Mission Specialist: Kalpana Chawla, an Indian-born aerospace engineer on her second space mission.

- Mission Specialist: David M. Brown, a US Navy captain trained as an aviator and flight surgeon. Brown worked on a number of scientific experiments.

- Mission Specialist: Laurel Clark, a US Navy commander and flight surgeon. Clark worked on a number of biological experiments.

Debris strike during launch

STS-107 had been delayed 13 times over the course of two years (despite its designation as the 107th mission, it was actually the 113th mission) from its original launch date of 11 January 2001 to its actual launch date of 16 January, 2003. A well-publicized launch delay due to cracks in the shuttle's propellant system occurred one month before a 19 July, 2002 launch date, but the CAIB determined that this delay had nothing to do with the catastrophic failure 6 months later.

Video taken during lift-off was routinely reviewed two hours after the launch, which revealed nothing unusual. The following day, higher-resolution film that had been processed overnight revealed that a piece of insulation foam fell from an external fuel tank 81.9 seconds after launch and appeared to strike the shuttle's left wing near RCC panels 5 through 9. Soon after, there were three separate requests for in-orbit imaging to more precisely determine damage. According to the CAIB report, the Mission Management Team declared the debris strike a "turnaround" issue and did not pursue a request for imagery [1] (http://anon.nasa-global.speedera.net/anon.nasa-global/CAIB/CAIB_lowres_full.pdf).

Destruction during re-entry

Columbia_debris_falling_in_the_sky.jpg

At 2:30 a.m. EST on February 1, 2003, the Entry Flight Control Team began duty in the Mission Control Center. The Flight Control Team was not working any issues or problems related to the planned de-orbit and re-entry of Columbia. In particular, the team indicated no concerns about the debris impact to the left wing during ascent, and treated the re-entry like any other. The team worked through the de-orbit preparation checklist and re-entry checklist procedures. Weather forecasters, with the help of pilots in the Shuttle Training Aircraft, evaluated landing site weather conditions at the Kennedy Space Center. At the time of the de-orbit decision, about 20 minutes before the initiation of the de-orbit burn, all weather observations and forecasts were within guidelines set by the flight rules, and all systems were normal.

Shortly after 8:00 a.m., the Mission Control Center Entry Flight Director polled the Mission Control room for a GO/NO-GO decision for the de-orbit burn, and at 8:10 a.m., the Capsule Communicator notified the crew they were GO for de-orbit burn.

As the Orbiter flew upside down and tail-first over the Indian Ocean at an altitude of 175 statute miles, Commander Husband and Pilot McCool executed the de-orbit burn at 8:15:30 a.m. using Columbia’s two Orbital Maneuvering System engines. The de-orbit maneuver was performed on the 255th orbit, and the 2-minute, 38-second burn slowed the Orbiter from 17,500 mph to begin its re-entry into the atmosphere. During the de-orbit burn, the crew felt about 10 percent of the effects of gravity. There were no problems during the burn, after which Husband maneuvered Columbia into a right-side-up, forward-facing position, with the Orbiter’s nose pitched up.

Entry Interface, arbitrarily defined as the point at which the Orbiter enters the discernible atmosphere at 400,000 feet, occurred at 8:44:09 a.m. (Entry Interface plus 000 seconds, written EI+000) over the Pacific Ocean. As Columbia descended from space into the atmosphere, the heat produced by air molecules colliding with the Orbiter typically caused wing leading-edge temperatures to rise steadily, reaching an estimated 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit during the next six minutes. As superheated air molecules discharged light, astronauts on the flight deck saw bright flashes envelop the Orbiter, a normal phenomenon.

At 8:48:39 a.m. (EI+270), a sensor on the left wing leading edge spar showed strains higher than those seen on previous Columbia re-entries. This was recorded only on the Modular Auxiliary Data System, and was not telemetered to ground controllers or displayed to the crew.

At 8:49:32 a.m. (EI+323), traveling at approximately Mach 24.5, Columbia executed a roll to the right, beginning a pre-planned banking turn to manage lift, and therefore limit the Orbiter’s rate of descent and heating.

Columbia_debris_detected_by_radar.jpg

At 8:50:53 a.m. (EI+404), traveling at Mach 24.1 and at approximately 243,000 feet, Columbia entered a 10-minute period of peak heating, during which the thermal stresses were at their maximum. By 8:52:00 a.m. (EI+471), nearly eight minutes after entering the atmosphere and some 300 miles west of the California coastline, the wing leading-edge temperatures usually reached 2,650 degrees Fahrenheit. Columbia crossed the California coast west of Sacramento at 8:53:26 a.m. (EI+557). Traveling at Mach 23 and 231,600 feet, the Orbiter’s wing leading edge typically reached more than an estimated 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

Now crossing California, the Orbiter appeared to observers on the ground as a bright spot of light moving rapidly across the sky. Signs of debris being shed were sighted at 8:53:46 a.m. (EI+577), when the superheated air surrounding the Orbiter suddenly brightened, causing a noticeable streak in the Orbiter’s luminescent trail. Observers witnessed another four similar events during the following 23 seconds, and a bright flash just seconds after Columbia crossed from California into Nevada airspace at 8:54:25 a.m. (EI+614), when the Orbiter was traveling at Mach 22.5 and 227,400 feet. Witnesses observed another 18 similar events in the next four minutes as Columbia streaked over Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

In Mission Control, re-entry appeared normal until 8:54:24 a.m. (EI+613), when the Maintenance, Mechanical, and Crew Systems (MMACS) officer informed the Flight Director that four hydraulic sensors in the left wing were indicating “off-scale low,” a reading that falls below the minimum capability of the sensor. As the seconds passed, the Entry Team continued to discuss the four failed indicators.

At 8:55:00 a.m. (EI+651), nearly 11 minutes after Columbia had re-entered the atmosphere, wing leading edge temperatures normally reached nearly 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. At 8:55:32 a.m. (EI+683), Columbia crossed from Nevada into Utah while traveling at Mach 21.8 and 223,400 ft. Twenty seconds later, the Orbiter crossed from Utah into Arizona.

At 8:56:30 a.m. (EI+741), Columbia initiated a roll reversal, turning from right to left over Arizona. Traveling at Mach 20.9 and 219,000 feet, Columbia crossed the Arizona-New Mexico state line at 8:56:45 (EI+756), and passed just north of Albuquerque at 8:57:24 (EI+795).

Around 8:58:00 a.m. (EI+831), wing leading edge temperatures typically decreased to 2,880 degrees Fahrenheit. At 8:58:20 a.m. (EI+851), traveling at 209,800 feet and Mach 19.5, Columbia crossed from New Mexico into Texas, and about this time shed a Thermal Protection System tile, which was the most westerly piece of debris that has been recovered. Searchers found the tile in a field in Littlefield, Texas, just northwest of Lubbock. At 8:59:15 a.m. (EI+906), MMACS informed the Flight Director that pressure readings had been lost on both left main landing gear tires. The Flight Director then told the Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) to let the crew know that Mission Control saw the messages and was evaluating the indications, and added that the Flight Control Team did not understand the crew’s last transmission.

At 8:59:32 a.m. (EI+923), a broken response from the mission commander was recorded: “Roger, uh, bu - [cut off in mid-word] …” It was the last communication from the crew and the last telemetry signal received in Mission Control. Videos made by observers on the ground at 9:00:18 a.m. (EI+969) revealed that the Orbiter was disintegrating.

At about 9:05 (14:05 UTC), residents of north central Texas reported a loud boom, a small concussion wave and smoke trails and debris in the clear skies above the counties southeast of Dallas. More than 2,000 debris fields, as well as human remains, were found in sparsely populated areas southeast of Dallas from Nacogdoches in East Texas, where a lot of debris fell, to western Louisiana and the southwestern counties of Arkansas. This debris included live earthworms from a science package that survived the re-entry. NASA issued warnings to the public that any debris could contain hazardous chemicals, that it should be left untouched, its location reported to local emergency services, or government authorities and that anyone in unauthorized possession of debris would be prosecuted.

Shortly after being told of reports of pieces of the shuttle being seen to break away, the NASA flight director declared a contingency (events leading to loss of the vehicle) and alerted search and rescue teams in the area, telling all controllers to "lock the doors" or preserve all the mission data for later investigation.

Response from the President

At 14:04 EST (19:04 UTC), a somber President Bush addressed America: "This day has brought terrible news and great sadness to our country... The Columbia is lost; there are no survivors." Despite the major setback, the President reassured Americans that the space program would continue: "The cause in which they died will continue... Our journey into space will go on."

Initial investigation and fears

NASA's Space Shuttle Program Manager, Ron Dittemore, reported that "The first indication was loss of temperature sensors and hydraulic systems on the left wing. They were followed seconds and minutes later by several other problems, including loss of tire pressure indications on the left main gear and then indications of excessive structural heating." Analysis of 31 seconds of telemetry data which had initially been filtered out because of data corruption within it showed the shuttle fighting to maintain its orientation, eventually using maximum thrust from its reaction control system jets.

The focus of the investigation centered on the foam strike from the very beginning. Incidents of debris strikes causing damage during take-off were already well known and had actually damaged space shuttles, specifically during STS-45 and STS-27. [2] (http://csel.eng.ohio-state.edu/woods/space/Create%20foresight%20Col-draft.pdf)

Despite some initial and perhaps understandable fears that the addition of the first Israeli astronaut to the crew had made the Columbia a more likely target for terrorists, there is no evidence to support any theory that terrorism was involved. In any case, security surrounding the launch and landing of the space shuttle had been increased to ward off any potential terrorist attack[3] (http://www.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/meast/02/01/shuttle.israel.reax/). The Cape Canaveral launch facility, like all sensitive government areas, had increased security measures put in place in the wake of the September 11 attack. In addition, the extremely high altitude of the shuttle when the incident occurred ruled out all but the most sophisticated of terrorists. Gordon Johndroe, spokesman for the United States Department of Homeland Security, stated: "There is no information at this time that this was a terrorist incident."

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board

Following protocols established after the loss of Challenger an independent investigating board was created immediately following the accident. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board, or CAIB, consisted of expert military and civilian analysts who investigated the accident in great detail.

Columbia's data recorder was found near Hemphill, Texas on March 20, 2003. Because Columbia was more of a test vehicle than the other orbiters, the data recorder contained very extensive logs of structural and other data which allowed the CAIB to reconstruct many of the events during the process leading to breakup, often using the loss of signals from sensors on the wing to track how the damage progressed. This was correlated with analysis of debris and tests to obtain a final conclusion about the probable events.

NASA officials released experimental findings on May 30 proving that the insulation known to have hit the leading edge of Columbia's left wing could have created a gap between protective RCC panels. The findings showed that a joint, known as a T-seal, shifted after being hit with foam insulation traveling at the same speed the actual foam was traveling when it hit the left wing. The gap was small, 0.6 cm × 55 cm, but some researchers not on the investigation team have stated that a gap of that size was sufficiently large to act as a catalyst for further widening during re-entry. On June 24, the investigators more confidently declared the flyaway foam to be "the most probable cause" of the wing damage.

On August 26, the CAIB issued its report on the accident. The board report confirmed the immediate cause of the accident as a breach in the leading edge of the left wing, caused by insulating foam shed during launch. The report also delved deeply into the underlying organizational and cultural issues that led to the accident. The report was highly critical of NASA's decision-making and risk-assessment processes, to the point of concluding that whoever was in the key decision-making positions, the systems and roles were arranged so that safety compromise could be expected. This included the position of Shuttle Program Manager, a role in which one individual was responsible for achieving safety, timely launches and acceptable costs, each a goal conflicting with the others. It found that NASA had institutionally accepted deviations from design criteria as normal when they happened on several flights and did not lead to fatal consequences. One of those was the conflict between a design specification saying that the heat shielding system did not need to withstand impact damage and the common occurrence of impact damage to it during flight. The board made recommendations for significant changes in processes and culture.

In late July 2003, an Associated Press poll revealed that Americans' support for the space program remained strong, despite the tragedy. Two-thirds believed the space shuttle should continue to fly and nearly three-quarters said that the space program was a good investment. On the question of sending humans to Mars, 49 percent thought it was a good idea, while 42 percent opposed it. Support slipped for sending civilians like teachers into space with 56 percent supporting the idea and 38 percent opposed.

The "mysterious purple streak"

The San Francisco Chronicle reported on February 5, 2003, that an unnamed amateur San Francisco astronomer had imaged Columbia with a Nikon 880 digital camera at around the time the shuttle first started showing indications of trouble, at an altitude of some 40 miles. The Chronicle reported that "in the critical shot, a glowing purple rope of light corkscrews down toward the plasma trail, appears to pass behind it, then cuts sharply toward it from below. As it merges with the plasma trail [produced by the shuttle], the streak itself brightens for a distance, then fades." [4] (http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2003/02/11/MN150539.DTL) The camera in question was sent to Houston for further investigation by NASA. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board subsequently concluded that this was an artifact caused by a faulty camera. Nikon has said that the model of camera used is known to occasionally produce a purple fringe on photographs as a result of "color interpolation combined with chromatic aberration", an effect that has been reproduced by independent reviewers [5] (http://www.worldnetdaily.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=30904). Purple fringing, a result of the optical phenomenon of chromatic aberration, is a problem with many types of digital camera and not just the Nikon 880.

It has also been proposed that this streak may have been a bolt of positive lightning; NASA and other scientists have discounted this possibility.

Conspiracy theories

Some conspiracy theorists have suggested that the United States Air Force shot the craft down with a laser (accidentally or deliberately). This explanation has attracted little mainstream support and is generally regarded as a fringe conspiracy theory. It would also not explain the image captured by the San Francisco astronomer, as the beam of the high-energy Chemical Oxygen Iodine Laser (COIL) system used by the Air Force operates at the infrared wavelength and so is not visible to the human eye. [6] (http://optics.org/articles/ole/9/3/2/1)

Close-up photographs have been made of the Soviet space shuttle Buran after its single successful, unmanned obital flight. These 1988 photos show rather extensive damage to the wing's leading edge. Critics argue the Columbia could not have been destroyed due to RCC tile damage, as Buran, which was of similar design, survived.

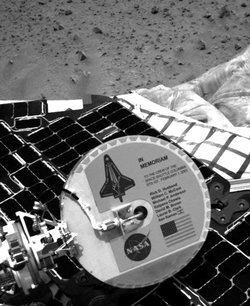

Memorials

On February 4, 2003, President George W. Bush and his wife, Laura, led a memorial service at the LBJ Space Center, which was intended for the NASA family, for the families of the loved ones of the astronauts. The service which was meant for the nation came two days later, when Vice-President Richard Cheney and his wife, Lynne, led official Washington in paying tribute at a similar service at Washington National Cathedral. During that service, singer Patti LaBelle sang "Way up There." [7] (http://media.cathedral.org/ColumbiaDSL.wmv)

On March 26 the United States House of Representatives' Science Committee approved funds for the construction of a memorial at Arlington National Cemetery for the STS-107 crew. A similar memorial was built at the cemetery for the last crew of Space Shuttle Challenger.

On August 6, 2003, NASA announced [8] (http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2003/aug/HQ_03259_astroids_dedicated.html) that the IAU had approved naming seven asteroids discovered in July 2001 at the Mount Palomar observatory in honor of the seven astronauts: 51823 Rickhusband, 51824 Mikeanderson, 51825 Davidbrown, 51826 Kalpanachawla, 51827 Laurelclark, 51828 Ilanramon, 51829 Williemccool.

A mountain peak near Kit Carson Peak in the Sangre de Cristo mountains was renamed Columbia Point. A dedication plaque was placed on the point in August, 2003.

On October 28, 2003, the names of the astronauts were added to the Astronaut Memorial at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.

On January 6, 2004, NASA announced that the landing site of the recently landed Mars rover Spirit would henceforth be known as Columbia Memorial Station. On February 2, it was also announced that NASA was naming a complex of hills east of the landers 'The Columbia Hills', after the crew of Columbia.

Political aftermath for the space program

Following the loss of Columbia, the space shuttle program was suspended. The expansion of International Space Station was also delayed, as the space shuttles were the delivery vehicle for station modules. The station was supplied and crews exchanged using Russian manned Soyuz spacecraft and unmanned Progress ships.

Less than a year later, Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration, calling for the retirement of the space shuttle fleet following the completion of the International Space Station and the development of the Crew Exploration Vehicle. NASA planned to return the space shuttle to service around September 2004. That date has since been pushed back to July 2005 (see NASA's Return To Flight page (http://www.nasa.gov/news/highlights/returntoflight.html) for current details).

See also

External links

- NASA flight STS-107 (http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/shuttle/archives/sts-107/)

- JPL at Caltech: Tribute to the Crew of Columbia (http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/releases/2003/columbia-tribute.cfm) (the seven citations)

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (http://www.caib.us/)

- Shuttle Orbiter Columbia (OV-102) (http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/resources/orbiters/columbia.html)

- President Bush's address to America (http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/02/20030201-2.html) - February 1, 2003

- President Bush's remarks at memorial service (http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/02/20030204-1.html) - February 4, 2003

- Columbia Loss FAQ (http://www.io.com/~o_m/clfaq/clfaq.htm) - a discussion of the Columbia disaster

- Video reconstruction of Columbia's final reentry (http://www.chrisvalentines.com/sts107/)

- How the use of PowerPoint may have contributed to the disaster, according to Edward Tufte (http://www.edwardtufte.com/bboard/q-and-a-fetch-msg?msg_id=0000Rs&topic_id=1&topic=Ask%20E%2eT%2e)

de:Columbia (Raumfähre) he:אסון הקולומביה pt:Acidente do vaivém espacial Columbia