Roman law

|

|

Roman Law is the legal system of ancient Rome. The development of Roman law covers more than a thousand years from the law of the twelve tables (from 449 BC) to the codification of Emperor Justinian I (around 530). Roman law as preserved in Justinian's codes became the basis of legal practice in the Byzantine Empire and—later— in continental Western Europe

Using the term Roman law in a broader sense, one may say that Roman law is not only the legal system of ancient Rome but the law that was applied throughout most of Europe until the end of the 18th century. In some countries like Germany the practical application of Roman law lasted even longer. For these reasons, many modern legal systems in Europe and elsewhere are heavily influenced by Roman law. This is especially true in the field of private law. Even the English and North American Common law owes some debt to Roman law although Roman law exercised much less influence on the English legal system than on the legal systems of the continent.

| Contents |

The history of Roman law in antiquity

The Roman Republic

It is impossible to give an exact date for the beginning of the development of Roman law. The first legal text the content of which is known to us in some detail is the law of the twelve tables. It was drafted by a committee of ten men (decemviri legibus scribundis) in the year 449 BC. The fragments which have been preserved show that it was not a law code in the modern sense. It did not aim to provide a complete and coherent system of all applicable rules or to give legal solutions for all possible cases. Rather, the twelve tables contain a number of specific provisions designed to change the customary law already in existence at the time of the enactment. The provisions pertain to all areas of law. However, the largest part seems to have been dedicated to private law and civil procedure.

Another important statute from the Republican era is the lex Aquilia of 286 BC, which may be regarded as the root of modern tort law. However, Rome�s most important contribution to European legal culture was not the enactment of well-drafted statutes, but the emergence of a class of professional jurists and of a legal science. This was achieved in a gradual process of applying the scientific methods of Greek philosophy to the subject of law—a subject which the Greeks themselves never treated as a science.

Traditionally, the origins of Roman legal science are being connected to the story of Gnaeus Flavius: Gnaeus Flavius is said to have published around the year 300 BC the formularies containing the words which had to be spoke in court in order to begin a legal action. Before the time of Gnaeus Flavius, these formularies are said to have been secret and known only to the priests. Their publication made it possible for non-priests to explore the meaning of these legal texts.—Whether or not this story is credible, jurists were active and legal treatises were written in larger numbers the 2nd century BC. Among the famous jurists of the republican period are Quintus Mucius Scaevola who wrote voluminous treatise on all aspects of the law, which was very influential in later times, and Servius Sulpicius Rufus a friend of Marcus Tullius Cicero. This, Rome had developed a very sophisticated legal system and a refined legal culture when the Roman republic was replaced by the monarchical system of the principate in 27 BC.

Classical Roman law

The first 250 years AD are the period during which Roman law and Roman legal science reached the highest degree of perfection. The law of this period is often referred to as classical Roman law. The literary and practical achievements of the jurists of this period gave Roman law its unique shape.

The jurists worked in different functions: They gave legal opinions at the request of private parties. They advised the magistrates who were entrusted with the administration of justice, most importantly the praetors. They helped the praetors draft their edicts, in which they publicly announced at the beginning of their tenure, how they would handle their duties, and the formularies, according to which specific proceedings were conducted. Some jurists also held high judicial and administrative offices themselves.

The jurists also produced all kinds of legal commentaries and treatises. Around 130 the jurist Salvius Iulianus drafted a standard form of the praetor�s edict, which was used by all praetors from that time onwards. This edict contained detailed descriptions of all cases, in which the praetor would allow a legal action and in which he would grant a defense. The standard edict thus functioned like a comprehensive law code, even though it did not formally have the force of law. It indicated the requirements for a successful legal claim. The edict therefore became the basis for extensive legal commentaries by later classical jurists like Iulius Paulus and Domitius Ulpianus .

The new concepts and legal institutions developed by pre-classical and classical jurists are too numerous to mention here. Only a few examples are given here:

- Roman jurists clearly separated the legal right to use a thing (ownership) from the factual ability to use and manipulate the thing (possession). They also found the distinction between contract and tort as sources of legal obligations.

- The standard types of contract (sale, contract for work, hire, contract for services) regulated in most continental codes and the characteristics of each of these contracts were developed by Roman jurisprudence.

- The classical jurist Gaius (around 160) invented a system of private law based on the division of all material into personae (persons), res (things) and actiones (legal actions). This system was used for many centuries. It can be recognized in legal treatises like William Blackstone 's Commentaries on the Laws of England and enactments like the French Code civil.

Post-classical law

By the middle of the 3rd century the conditions for the flourishing of a refined legal culture had become less favorable. The general political and economic situation deteriorated. The emperors assumed more direct control of all aspects of political life. The political system of the principate, which had retained some features of the republican constitution began to transform itself into the absolute monarchy of the dominate. The existence of a legal science and of jurists who regarded law as a science, not as an instrument to achieve the political goals set by the absolute monarch did not fit well into the new order of things. The literary production all but ended. Few jurists after the mid-third century are known by name. While legal science and legal education persisted to some extent in the eastern part of the empire, most of the subtleties of classical law came to be disregarded and finally forgotten in the west. Classical law was replaced by so-called vulgar law. Where the writings of classical jurists were still known, they were edited to conform to the new situation.

The introduction of Christianity as state religion under emperor Theodosius II, which lead to the suppression of pagan learning, may have contributed to the deterioration of Roman legal culture.

Justinian's codification

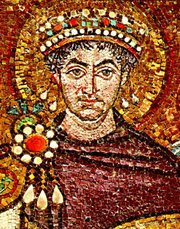

Emperor Justinian I, who temporarily regained control of larger parts of the empire which his predecessors had lost to Germanic tribes, set out to restore Roman law. For this purpose, he commissioned the production of three great law codes. Most of what we know about Roman law comes from these codes.

- The first code was a collection of imperial laws from the time of Hadrian (117—138) to Justinian himself. This code, called Codex Iustinianus (in English: the Code), was published in 529. A revised version was issued in 534.

- The second and more important work was a collection of excerpts from the writings of the classical jurists. This collects, called Digesta (in English: the Digest) or Pandectae was published in 533. The legal opinions of the jurists contained in the excerpts were given the force of law. The Digest is our most important source of information on classical Roman law. Only very few traces of the classical writings have survived outside this collection.

- Finally, Justinian ordered the production of a textbook for beginners, known as the Institutiones (in English: the Institututes). The textbook of Gaius (see above) was used as a model. The textbook, too, was given the force of law and published in 533.

- Justinian had planned to complete his codification by the promulgation of a collection of new statues enacted after the publication of the Codex. However, this plan was never realized. Only private collections of later statutes (called novellae—new laws) have come down to us.

In the middle ages, the three official codes and the novellae were given the collective name of Corpus Iuris Civilis (body of the civil law).

The application of Roman law in the provinces of the Empire

In retrospect, and as it was revived in Western Europe in the 11th century, classical Roman law appears more monolithic than it was in its effects on contemporary people's lives. From the beginning of Rome's expansion, exceptions to Roman practice were granted in a multitude of treaties with individual cities as they were conquered, which were customarily set up publicly in inscriptions, many fragments of which survive, and in addition, at least under the Principate, conquerors and governors were given wide latitude in the terms under which they made rulings, subject to the imperium of Senate or Emperor. A fundamental principle of Roman private law was an individual's right to be judged according to his status and under the law of his origin, the principle under which Roman citizens like Paul of Tarsus expected to be judged. What does not emerge, is a sense that Roman authorities sought to unify all subjects under a single codification (MacMullen 2000 p 11 etc).

- Ramsay MacMullen, 2000. Romanization in the Time of Augustus (Yale university Press).

The afterlife of Roman law in the middle ages and in modern times

Roman law in the eastern empire

In the byzantine empire, the codes of Justinian became the basius of legal practice. In the 9th century, the emperors Basileios I and Leon VI commissioned a combined translation of the Code and the Digest into Greek, which became known as the Basilica. Roman law as preserved in the codes of Justinian and in the Basilika remained the basis of legal practice in Greece and in the courts of the orthodox church even after the fall of the Byzantine empire and the conquest by the Turks.

Roman law in the west

In the west, Justinian�s codes were almost immediately forgotten. While the Code and the Institutes remained known (though they had little influence on legal practice ion the early middle ages), the Digest was completely ignored for several centuries. Around 1070 however, a manuscript of the Digest was rediscovered in Italy. From that time, scholars began to study the ancient Roman legal texts and to teach others what they learned from their studies. The center of these studies was Bologna. The law school there gradually developed in one of Europe�s first universities.

The students, who were taught Roman law in Bologna (and later in many other places) found that many rules of Roman law were better suited to regulate complex economic transactions than the customary rules, which were applicable throughout Europe. For this reason, Roman law, or at least some provisions borrowed from it, began to be re-introduced into legal practice, centuries after the end of the Roman empire. This process was actively supported by many kings and princes who employed university-trained jurists as counselors and court officials and sought to benefit from rules like the famous Princeps legibus solutus est (The sovereign is not bound by the laws).

By the middle of the 16th century, the rediscovered Roman law dominated the legal practice in most European countries. A legal system, in which Roman law was mixed with elements of canon law and of Germanic custom, especially feudal law, had emerged. This legal system, which was common to all of continental Europe (and Scotland) was known as Ius Commune. This Ius Commune and the legal systems based on it are usually refered to as civil law in English-speaking countries.

Only England did not take part in the reception of Roman law. One reason for this is the fact that the English legal system was more developed than its continental counterparts by the time Roman law was rediscovered. Therefore, the practical advantages of Roman law were less obvious to English practitioners than to continental lawyers. Later, the fact that Roman law was associated with the Holy Roman Empire, the Roman Catholic Church and with absolutism made Roman law unacceptable in England. Even so, some concepts from Roman law made their way into the common law. Especially in the early 19th century, English lawyers and judges were willing to borrow rules and ideas from continental jurists and directly from Roman law.

The practical application of Roman law and the era of the European Ius Commune came to an end, when national codifications were made. In 1804, the French civil code came into force. In the course of the 19th century, many European states either adopted the French model or drafted their own codes. In Germany, the political situation made the creation of a national code of laws impossible. In some parts of Germany, Roman law continued to be applied until the German civil code (B�rgerliches Gesetzbuch) came into force in 1900.

Roman law today

Today, Roman law is no longer applied in legal practice, even though the legal systems of some states like South Africa and San Marino are still based on the old Ius Commune. However, even where the legal practice is based on a code, many rules deriving from Roman law apply: No code completely broke with the Roman tradition. Rather, the provisions of Roman law were fitted into a more coherent system and expressed in the national language. For this reason, knowledge of Roman law is indispensable to understand the legal systems of today. Thus, Roman law is often still a mandatory subject for law students in civil law jurisdictions.

As steps towards a unification of the private law in the member states of the European Union are being taken, the old Ius Commune, which was the common basis of legal practice everywhere, but allowed for many local variants, is seen by many as a model.

Web links

A very good colection of resources maintained by professor Ernest Metzger (http://www.iuscivile.com).