Reichstag fire

|

|

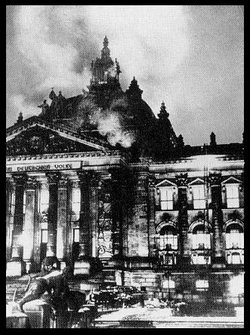

The Reichstag fire, a pivotal event in the establishment of Nazi Germany, began at 9:14 PM on the night of February 27, 1933, when a Berlin fire station received an alarm that the Reichstag building, assembly location of the German Parliament, was ablaze. The fire seemed to have been started in several places, and by the time the police and firemen arrived a huge explosion had set the main Chamber of Deputies in flames. Looking for clues, the police quickly found Marinus van der Lubbe, half-naked, cowering behind the building. Van der Lubbe was a mentally ill former Dutch Communist and unemployed bricklayer who had been floating around Europe for the last two years prior to 1933.

Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring arrived soon after, and when they were shown Van der Lubbe, a known Communist agitator, Göring immediately declared the fire was set by the Communists and had the party leaders arrested. Hitler took advantage of the situation to declare a state of emergency and encouraged aging president Paul von Hindenburg to sign the Reichstag Fire Decree, abolishing most of the human rights provisions of the 1919 Weimar Republic constitution.

The Nazi leaders were determined to demonstrate the Reichstag Fire was a deed of the Comintern, and in early March 1933, three men were arrested who were to play pivotal roles during the Leipzig Trial, known also as "Reichstag Fire Trial," namely three Bulgarians: Georgi Dimitrov, Vasil Tanev and Blagoi Popov. The Bulgarians were known to the Prussian police as senior Comintern operatives, but the police had no idea of how senior they were. Dimitrov was in charge of all Comintern operations in Western Europe.

| Contents |

Background

Hitler had been sworn in as Chancellor and head of the coalition government on January 30, 1933. His first act was to ask Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag so that he could increase the number of Nazi seats in the government. Hitler's request was granted and elections were set for March 5, 1933. Hitler's aim was to abolish democracy in a more or less legal fashion by activating the Enabling Act. The Enabling Act was a special power allowed by the Weimar Constitution to give the Chancellor the power to pass laws by decree, without the involvement of the Reichstag. The Enabling Act was only supposed to be used in times of extreme emergency, and in fact had only been used once before, in 1923-24 when the government used the Enabling Act to rescue Germany from hyper-inflation. To activate the Enabling Act required a vote by a two-thirds majority in the Reichstag. In January 1933, the Nazis had only 32% of the seats and thus were in no position to activate the Enabling Act.

During the election campaign, the Nazis had run on a platform of hysterical anti-communism, insisting that Germany was on the verge of a Communist revolution, and that the only way to stop the revolution was to pass the Enabling Act. Hitler's platform in the campaign comprised little more than demands that voters increase the Nazi share of seats so that the Enabling Act could be passed. In order to decrease the number of opposition members who could vote against the Enabling Act, Hitler had planned to ban the KPD (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands-Communist Party of Germany) after the elections and before the new Reichstag convened. The Reichstag Fire allowed Hitler to accelerate the banning of the Communist Party and was used to confirm Nazi claims of a pending Communist revolution. The Nazis argued the Reichstag fire was meant to serve as a signal to launch the revolution, and warned the German public about the grisly fate they would suffer under Communist rule.

Van der Lubbe's Confession and Its Consequences

According to the Berlin police, Van der Lubbe claimed to have set the fire as a protest against the rising power of the Nazis. Under torture, he confessed again and was brought to trial along with the leaders of the opposition Communist Party. As a consequence of the Reichstag Fire Decree, the Communist Party of Germany was banned on March 1, 1933, on the grounds that they were preparing a putsch. In the following days, the police and the SA seized all Communist Party buildings in Germany, along with weapons they claimed were to be used in the putsch. The K.P.D was the first political party banned by the Nazis.

With their leaders in jail and denied access to the press, the Communists were badly disorganized. Those Communist (and some Social Democratics) deputies that were elected to the Reichstag were prevented from taking their seats by the SA. The Nazis increased their share of the vote to 44%, which gave the Nazis and their coalition allies, the German National People's Party, who won 8% of the vote a 52% majority in the Reichstag. The March elections were a major success for the Nazis but not to the extent they were hoping for. (The Nazis had hoped to win 50%-55% of the vote.) The Nazis coerced and bribed the remaining parties except for the Social Democrats to give them the two-thirds majority for the Enabling Act, which gave them the right to rule by decree and suspended most civil liberties. Despite considerable pressure, only the S.P.D voted against the Enabling Act. In the months that followed, all of the non-Nazi parties were either banned or dissolved themselves.

Van der Lubbe's Execution

At his trial, Van der Lubbe was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was beheaded on January 10, 1934, three days before his 25th birthday. The Nazis alleged that Van der Lubbe was part of the Communist conspiracy to burn down the Reichstag and seize power, while the Communists alleged that Van der Lubbe was part of the Nazi conspiracy to blame the crime on them. Van der Lubbe for his part maintained that he had acted alone, claiming voices in his head had told him to burn down the Reichstag to protest the condition of the German working-class under Nazi rule.

Communist Party Leadership is Acquitted

The Leipzig Trial took part from September 21 to December 23,1933, and was presided over by judges from the old German Imperial Court, called the Reichsgericht. The Leipzig Trial was widely publicized and was broadcast on the radio. It was expected the court would find the Communists guilty on all counts and approve the repression and terror exercised by the Nazis against all opposition forces in the country. It was clear the first time Georgi Dimitrov spoke that would not happen. Dimitrov had given up his right to a court appointed lawyer and defended himself successfully. He proved his innocence and the innocence of his Communist comrades and was set free. In addition, he presented evidence that the organizers of the fire were senior members of the Nazi Party.

Hitler was furious with the outcome of this trial. He decreed that henceforth treason – among many other offenses – would only be tried by a newly established Volksgerichtshof ("People's Court"), which became infamous for the enormous number of death sentences it handed down while led by Roland Freisler.

Dispute about Van der Lubbe's Role in the Reichstag Fire

Historians generally agree that Van der Lubbe, sometimes described as a "half-wit," was involved in the Reichstag Fire. The extent of the damage, however, has led to considerable debate over whether he acted alone. Considering the speed with which the fire engulfed the building, Van der Lubbe's reputation as a mentally-deranged fool hungry for fame, and cryptic comments by leading Nazi officials, it is generally believed the Nazi hierarchy was involved in order to reap political gain—and it obviously did. Others have contended that neither the Nazis nor Communists were behind the fire, and that van der Lubbe acted alone. According to this view, the Reichstag Fire was a stroke of good luck for the Nazis. The historian Hans Mommsen has shown that the Nazi leadership was in a state of panic the night of the Reichstag Fire, and they seemed to have regarded the Reichstag Fire as a confirmation of all their propaganda about a Communist revolution being imminent was actually true.

Göring's Possible Role

At Nuremberg, General Franz Halder claimed Göring had confessed to setting the fire: "At a luncheon on the birthday of Hitler in 1942, the conversation turned to the topic of the Reichstag building [fire] and its artistic value. I heard with my own ears when Göring interrupted the conversation and shouted: 'The only one who really knows about the Reichstag is I, because I set it on fire!' With that he slapped his thigh with the flat of his hand."

Göring denied he had any involvement in the fire. "I had nothing to do with it. I deny this absolutely. I can tell you in all honesty, the Reichstag fire proved very inconvenient to us. After the fire I had to use the Krolloper House as the new Reichstag, and the opera seemed to me much more important than the Reichstag. I must repeat, no pretext was needed for taking measures against the Communists. I already had a number of perfectly good reasons in the forms of murders, etc."

"Counter-trial" Organized by the German Communist Party

During the summer of 1933, a counter-trial was organized in London by a group of lawyers, democrats and other anti-Nazi propagandists under the aegis of German Communist Émigrés. The Chairman of the "Counter-trial" was the Labour politician Sir Stafford Cripps, but the chief organizer behind the "counter-trial" was KPD's propaganda chief Willi Münzenberg. The counter-trial lasted one week and ended with the conclusion the defendants were innocent, and the true initiators of the fire are found amid the leading NSDAP elite. Göring was found guilty at the counter-trial. The counter-trial served as a workshop during which all possible scenarios were tested and all speeches of the defendants were prepared. The "Counter-trial" was an enormously successful publicity stunt for the German Communists. Münzenberg followed this triumph with another by have written under his name the best-selling The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire, an expose of what Münzenberg alleged to be the Nazi conspiracy to burn down the Reichstag and blame the act on the Communists (In fact, like all of Münzenberg's books, the real author was one of his aides, in this case a Czechoslovak Communist named Otto Katz). Today, The Brown Book is widely seen as worthless by historians.

Notable Defendants in the Reichstag Fire Trial:

Reference

- Kershaw, Ian Hitler, 1889-1936: Hubris, London, 1998.

- Mommsen, Hans "The Reichstag Fire and Its Political Consequences" pages 129-222 from Republic to Reich The Making of the Nazi Revolution edited by Hajo Holborn, New York: Pantheon Books, 1972: orginally published as "Der Reichstagsbrand und seine politischen Folgen" pages 351-413 from Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 12, 1964.

- Synder, Louis Encyclopedia of the Third Reich, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

- Tobias, Fritz The Reichstag Fire, translated From the German by Arnold J. Pomerans with an introduction by A. J. P. Taylor, New York, Putnam 1964, 1963.

de:Reichstagsbrand es:Incendio del Reichstag fr:Incendie du Reichstag he:שריפת הרייכסטאג it:Incendio del Reichstag ja:ドイツ国会議事堂放火事件 pt:Reichstag (prédio)