Parthia

|

|

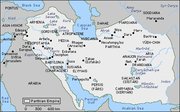

The Parthian Empire was the dominating force on the Iranian plateau beginning in the late 3rd century BCE, and intermittently controlled Mesopotamia between ca 190 BCE and 224 CE. Parthia was the arch-enemy of the Roman Empire in the East and it limited Rome's expansion beyond Cappadocia (central Anatolia).

The Parthian empire was the most enduring of the empires of the ancient Near East. After the Parni nomads had settled in Parthia and had built a small independent kingdom, they rose to power under king Mithradates the Great (171-138 BCE). The Parthian empire occupied all of modern Iran, Iraq and Armenia, parts of Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and, for brief periods, territories in Pakistan, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. The end of this loosely organized empire came in 224 CE, when the last king was defeated by one of the empire's vassals, the Persians of the Sassanid dynasty.

| Contents |

Origins

The Parthians were a member of the Parni tribe (a name whose relation to the word Parthian is much debated, or according to Armenian sources, of White Hun origins), nomadic Persians who are thought to have spoken an Iranian language, and who arrived at the Iranian plateau from Central Asia. They were consummate horsemen, known for the 'Parthian shot': turning backwards at full gallop to loose an arrow directly to the rear. Later, at the height of their power, Parthian influences reached as far as Ubar in Arabia, the nexus of the frankincense trade route, where Parthian-inspired ceramics have been found. The power of the early Parthian empire seems to have been overestimated by some ancient historians, who could not clearly separate the latter, very strong empire from its rather obscure origins.

Little is known of the Parthians; they had no literature of their own and consequently their written history consists of biased descriptions of conflicts with Romans, Greeks, Jews and — at the far end of the Silk Road — the Chinese empire. Even their own name for themselves is up for debate due to a lack of domestic records; the best guess is that they called their empire Iranshahr. Their strength was a combination of the guerilla warfare of a mounted nomadic tribe and sufficient organisation to build a vast empire, even if it never matched the two Persian empires in strength. Vassal kingdoms seem to have made up a large part of their territory (see Tigranes II of Armenia), and Hellenistic cities enjoyed a certain autonomy; their craftsmen received employment by some Parthians (illustration, above right).

The Parthian Empire

Initially, a king named Arsaces established his indepence from Seleucid rule in remote areas of northern Persia ca 250 BCE, where his descendants of the same name ruled until Antiochus III the Great briefly made them submit to Seleucid authority again in 206 BCE.

It was not until the 2nd century BCE that the Parthians profited from the continuing erosion of Seleucid power and gradually captured all of their territories east of Syria. Once the Parthians had captured Herat, the movement of trade along the Silk Road to China was effectively choked off and the post-Alexandrian Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was doomed. At its height, Parthia occupied areas now in Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine and Israel.

The task fell to the Seleucid monarchs to "hold the line" against the Parthian expansion. Antiochus IV Epiphanes spent his last years fruitlessly battling the Parthians in constant war, until his death in 163 BCE. The Parthians were able to take advantage of Seleucid weakness during the dynastic squabbles that followed Antiochus' death.

In 139 BCE, the Parthian king Mithridates I captured the Seleucid monarch, Demetrius Nicator, and held him captive for ten years, while his troops overwhelmed Mesopotamia and Media.

By 129 BCE the Parthians were in control of all the lands right to the Tigris River, and established their winter encampment at Ctesiphon on the banks of the Tigris downstream from modern Baghdad. Ctesiphon was a small suburb directly across the river from Seleucia, the most populous Hellenistic city of western Asia. Because of the need for the wealth and trade provided by Seleucia, the Parthian armies limited their incursions to harassment, allowing the city to preserve its independence and Greek culture. In the heat of the Mesopotamian summer, the Parthian horde would withdraw to the ancient Persian capitals of Susa and Ecbatana (modern Hamadan).

Government

After the conquest of Media, Assyria, Babylonia and Elam, the Parthians had to organize their empire. The former elites of these countries were Greek, and the new rulers had to adapt to their customs if they wanted their rule to last. As a result, the cities retained their ancient rights and civil administrations remained more or less undisturbed. An interesting detail is coinage: legends were written in the Greek alphabet, and this practice was continued in the 2nd century CE, when knowledge of this language was in decline and few people knew how to read or write the Greek alphabet.

Another source of inspiration was the Achaemenid dynasty that had once ruled the Persian Empire. Courtiers spoke Persian and used the Pahlavi script; the royal court traveled from capital to capital, and the Arsacid kings wanted to be called -as Cyrus the Great had ordered his subjects to do in the sixth century- "king of kings". This was a very apt title, as the Parthian monarch was the ruler of his own empire plus some eighteen vassal kings, such as the rulers of the city state Hatra, the port of Characene and the ancient kingdom of Armenia.

The empire was, overall, not very centralized. There were several languages, many peoples, and several different economic systems. The loose ties between the separate parts of the empire were the keys to its survival. In the 2nd century CE, the most important capital, Ctesiphon, was captured no less than three times by the Romans (in 116, 165 and 198 CE), but the empire survived because there were other centers of power. On the other hand, the fact that the empire was a mere conglomerate of kingdoms, provinces, marks, and city-states did at times seriously weaken the Parthian state. This was a major factor in the halt of the Parthian expansion after the conquests of Mesopotamia and Persia.

Local potentates played important roles, and the king had to respect their privileges. Several noble families had votes in the Royal council; the Sûrên clan had the right to crown the Parthian king, and every aristocrat was allowed and expected to retain an army of his own. When the throne was occupied by a weak ruler, divisions among the nobility became dangerous.

The constituent parts of the empire were surprisingly independent. For example, they were allowed to strike their own coins, a privelege which in antiquity was very rare. As long as the local elite paid tribute to the Parthian king, there was little interference. The system worked very well: towns like Ctesiphon, Seleucia, Ecbatana, Rhagae, Hecatompylus, Nisâ, and Susa flourished.

Tribute was one source of royal income; another was tolls. Parthia controlled the Silk Road, the trade route between the Mediterranean Sea and China.

Contact with China

Zhang_Qian.jpg

- "Anxi is situated several thousand li west of the region of the Great Yuezhi (in Transoxonia). The people are settled on the land, cultivating the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. They have walled cities like the people of Dayuan (Ferghana), the region contains several hundred cities of various sizes. The coins of the country are made of silver and bear the face of the king. When the king dies, the currency is immediately changed and new coins issued with the face of his successor. The people keep records by writing on horizontal strips of leather. To the west lies Tiaozi (Mesopotamia) and to the north Yancai and Lixuan (Hyrcania)." (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Parthian_art_1.jpg

Following Zhang Qian's embassy and report, commercial relations between China, Central Asia, and Parthia flourished, as many Chinese missions were sent throughout the 1st century BCE: "The largest of these embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred persons, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members... In the course of one year anywhere from five to six to over ten parties would be sent out." (Shiji, trans. Burton Watson).

The Parthians were apparently very intent on maintaining good relations with China and also sent their own embassies, starting around 110 BC: "When the Han envoy first visited the kingdom of Anxi (Parthia), the king of Anxi dispatched a party of 20,000 horsemen to meet them on the eastern border of the kingdom... When the Han envoys set out again to return to China, the king of Anxi dispatched envoys of his own to accompany them... The emperor was delighted at this." (Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

In 97 CE the Chinese general Ban Chao went as far west as the Caspian Sea with 70,000 men and established direct military contacts with the Parthian Empire.

Parthians also played a role in the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism from Central Asia to China. An Shih Kao, a Parthian nobleman and Buddhist missionary, went to the Chinese capital Luoyang in 148 CE where he established temples and became the first man to translate Buddhist scriptures into Chinese.

Conflicts with Rome

In 53 BCE, the Roman general Crassus invaded Parthia. However, he was defeated at the Battle of Carrhae by a Parthian commander who is called Surena in the Greek and Latin sources, and most likely was a member of the Sûrên clan. This was the beginning of a series of wars that were to last for almost three centuries.

The Parthian armies included two types of cavalry: the heavily-armed and armoured cataphracts and light brigades of mounted archers. For the Romans, who relied on heavy infantry, the Parthians were hard to defeat, as the cavalry was obviously much faster and more mobile. On the other hand, the Parthians found it difficult to occupy conquered areas as they were unskilled in siege warfare. Because of these weaknesses, neither the Romans nor the Parthians were able to thoroughly defeat each other, causing the wars to continue for centuries.

In the years following the battle of Carrhae, the Romans were divided in civil war between the adherents of Pompey and those of Julius Caesar. Because of the internal conflict, Rome was unable to campaign against Parthia. Although Caesar was eventually victorious against Pompey, his subsequent murder led to another civil war. The Roman general Quintus Labienus, who had supported Caesar's murderers and feared reciprocity from his heirs, Mark Antony and Octavian (later Augustus), sided with the Parthians and eventually became the best general of king Pacorus I. In 41 BCE, Parthia, led by Labienus, invaded Syria, Cilicia, and Caria and attacked Phrygia and Asia Minor. A second army intervened in Judaea and captured its king Hyrcanus II. The spoils were immense, and put to good use: king Phraates IV invested them in Ctesiphon, a new capital on the Tigris.

In 39 BCE, Mark Antony retaliated. Pacorus and Labienus were killed in action, and the Euphrates was again the border between the two nations, and the Parthians had learned that they could not occupy enemy territories without infantry. However, Mark Antony also wanted to avenge the death of Crassus and invaded Mesopotamia in 36 BCE with the legion VI Ferrata and other, unidentified units. He had cavalry with him, but it turned out to be unreliable, and the Romans were happy to have simply reached Armenia, having suffered great losses against the Parthians.

Mark Antony's campaing was followed by a break in the fighting between the two empires as Rome was again embroiled in civil war. When Octavian had defeated Mark Antony, he ignored the Parthians; he was more interested in the west. His son-in-law and future successor Tiberius negotiated a peace treaty with Phraates (20 BCE).

At the same time, around the year 1 CE, the Parthians became interested in the valley of the Indus, where they began conquering the petty kingdoms of Gandara. One of the Parthian leaders was named Gondopharnes, king of Taxila; according to an old and widespread Christian tradition, he was baptized by the apostle Thomas. While it may sound far-fetched, the story is not altogether impossible: adherents of several religions lived together in Gandara and the Punjab, and there may have been an audience for a representative of a new Jewish sect.

War broke out again between Rome and Parthia in the 60s CE. Armenia had become a Roman vassal kingdom, but the Parthian king Vologases I appointed a new Armenian ruler. This was too much for the Romans, and their commander Cnaeus Domitius Corbulo invaded Armenia. The result was that the Armenian king received his crown again in Rome from the emperor Nero. A compromise was worked out between the two empires: in the future, the king of Armenia was to be a Parthian prince, but his appointment required approval from the Romans.

Expansion to India

Main article:Indo-Parthian Kingdom

Also during the 1st century BCE, the Parthians started to make inroads into eastern territories that had been occupied by the Indo-Scythians and the Yuezhi. The Parthians gained control of all of Bactria and extensive territories in the Northern Subcontinent, after defeating many local rulers such as the Kushan Empire ruler Kujula Kadphises,in the Gandhara region.

Around 20 CE, Gondophares, one of the Parthian conquerors, declared his independence from the Parthian empire and established the Indo-Parthian Kingdom in the conquered territories.

Decline and fall

The Armenian compromise served its purpose, but nothing was arranged for the deposition of an Armenian king. After 110 CE, the Parthian king Vologases III dethroned the Armenian ruler, and the Roman emperor Trajan, a former general himself, decided to invade Parthia in retaliation. War broke out in 114 CE and the Parthians were severely beaten. The Romans conquered Armenia, and in the following year, Trajan marched to the south, where the Parthians were forced to evacuate their strongholds. In 116 CE, Trajan captured Ctesiphon, and established new provinces in Assyria and Babylonia.

MithradatesI.jpg

Rebellions soon broke out due to the continuing loyalty of the population to Parthia. At the same time, the diasporic Jews revolted and Trajan was forced to send an army to suppress them. Trajan overcame these troubles, but his successor Hadrian gave up the territories (117 CE). Nonetheless, it was clear that the Romans had learned how to defeat the Parthians.

Perhaps it was not Roman strength, but Parthian weakness that caused the disaster. In the first century CE, the Parthian nobility had become more powerful, due to concessions by the Parthian king granting them greater powers over the land and the peasantry. Their power now rivaled the king's, and at the same time internal divisions in the Arsacid family had rendered them vulnerable.

But the end was not near, yet. In 161 CE king Vologases IV declared war against the Romans and reconquered Armenia. The Roman counter-offensive was slow, but in 165 CE, Ctesiphon fell. The Roman emperors Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius added Mesopotamia to their realms, but were unable to demilitarize the region between the Euphrates and Tigris. It remained an expensive burden. But it was now clear that the Romans were superior for the time being.

The final blow came thirty years later. King Vologases V had tried to reconquer Mesopotamia during another Roman civil war (193 CE), but was repulsed when general Septimius Severus counter-attacked. Again, Ctesiphon was captured (198 CE), and large spoils were brought to Rome. According to a modern estimate, the gold and silver were sufficient to postpone a European economic crisis for three or four decades, and the consequences of the looting for Parthia were dire.

Parthia, now impoverished and without any hope to recover the lost territories, was demoralized. The kings were forced to concede greater powers to the nobility, and the vassal kings began to waver in their allegiance. In 224 CE, the Persian vassal king Ardašir revolted. Two years later, he took Ctesiphon, and this time it meant the end of Parthia, replaced by the second Persian Empire, ruled by the Sassanid dynasty.

Parthian rulers

External link

See also

- Parthia (Old Persian Parthava) (http://www.livius.org/pan-paz/parthia/parthia01.html|)bg:Партско царство

cs:Dynastie Arsakovců de:Parther eo:Parthoj fr:Parthie it:Parti nl:Parthen no:Parthia ja:パルティア pl:Partia (kraina) fi:Parthia sv:Partien