Miles M.52

|

|

| Contents |

Contract with Miles

The British Miles Aircraft company was responsible for a range of aircraft right back to the early days of flight, but their name is relatively unknown, not being associated with any of the great classic designs. In 1942 the Air Ministry and the Ministry of Aviation approached Miles with a top-secret contract, E.24/43, for a jet powered research plane designed to reach supersonic speeds. The contract called for an aeroplane capable of flying over 1,000 mph (1,600 km/h) in level flight, over twice the existing speed record, and climb to 36,000 feet (11,000 m) in 1.5 minutes.

Technical features

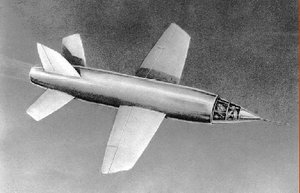

A huge number of advanced features were incorporated into the resulting M.52 design, many of which hint to a detailed knowledge of supersonic aerodynamics which, due to the war, took years to become public. In particular the design used very thin wings for low drag (see wave drag) and "clipped" the tips to keep them clear of the shock wave generated by the nose of the aircraft. Another critical addition was the use of an all-moving tail, key to supersonic flight control, which contrasts with traditional designs that use a two piece stabilizer/elevator design. Supersonic heating was not completely understood at the time, so the M.52 was built using stainless steel instead of duraluminum.

The design was to be powered by Frank Whittle's latest design, the Power Jets W.2/700. However this would not be able to provide the power needed for supersonic flight, so it incorporated an afterburner (called reheat in the UK). In order to supply more air to the afterburner than could move through the fairly small engine, a fan, powered by the engine, was installed in front of the assembly and blew air around the engine in ducts. Finally the design added another critical element, the use of a shock cone in the nose to slow the incoming air to the subsonic speeds needed by the engine. This design feature became common on many post-war aircraft.

The pilot sat in a small cockpit inside the conical shock cone in the nose of the aircraft, and in an emergency the entire area would be thrown free of the aircraft using explosive bolts. The pilot would then wait for the cockpit to slow, then exit and parachute to safety. The ability to exit the capsule was a serious concern however, it was not stable on its own at supersonic speeds, and likely would have tumbled, possibly breaking up.

Prototypes

In 1944 design work was considered 90% complete, and Miles was told to go ahead with the construction of three prototype M.52's. Later that year the Air Ministry signed an agreement with the United States to exchange high-speed research and data. The Bell Aircraft company was given all of the drawings and research on the M.52, but the US renegued on the agreement and no data was forthcoming in return. Unbeknownst to Miles, Bell had already started construction of a rocket powered supersonic design of their own, but were battling the problem of control. The Miles all-moving tail proved to be the solution to their problems.

Cancellation

At the close of World War II, the first of the three M.52's was more than 50% completed, with test flights only a few months away. However in February 1946 the new Labour government introduced a dramatic budget cut, and the Director of Scientific Research, Sir Ben Lockspeiser, canceled the project. The decision to cancel resulted from the fact that many captured German high-speed aircraft designs had featured swept-wings, and the government believed that attempting to break the sound barrier in a straight-wing aircraft such as the M.52 would be suicidal.

Subsequent work

Instead the government instituted a new programme involving expendable, pilotless, rocket-propelled missiles. The design was passed to Barnes Wallis at Vickers Armstrong, and the engine development took place at the RAE. The result was a 1/3rd sized scale model of the original M.52 design.

The first launch took place on 8th October 1947, but the rocket exploded shortly after launch. Only days later X-1 broke the sound barrier, and there was a flurry of denunciation of the Labour policies in research and development, with the Daily Express taking up the cause for the restoration of the M.52 programme, but to no effect. In October 1948 a second rocket was launched, and a speed of Mach 1.5 (1,800 km/h) was obtained. But, instead of diving into the sea as planned, the model ignored radio commands and was last observed (on radar) heading out into the Atlantic. At this point further work was cancelled.

Specifications

Engine: 1x Power Jets W.2/700 (fitted with augmentor and afterburner)

Wing Span: 27 ft (8.2 m)

Length: 28 ft (8.5 m)

Weight: 7,710 lb (3,500 kg)

Maximum Speed: 1,000 mph at 36,000 ft (1,600 km/h at 11,000 m)

Note: Some Soviet sources claim that the sound barrier was broken in the Soviet Union in 1946 using a captured German design, the DFS 346. No evidence for these claims was ever produced, and information on the DFS 346 testing program that has emerged since the collapse of the Soviet Union indicates that these claims were untrue.

Specifications (variant described)

General characteristics

- Crew:

- Capacity:

- Length: m ( ft)

- Wingspan: m ( ft)

- Height: m ( ft)

- Wing area: m² ( ft²)

- Empty: kg ( lb)

- Loaded: kg ( lb)

- Maximum takeoff: kg ( lb)

- Powerplant: Engine type(s), kN (lbf) thrust or

- Powerplant: Engine type(s), kW ( hp)

Performance

- Maximum speed: km/h ( mph)

- Range: km ( miles)

- Service ceiling: m ( ft)

- Rate of climb: m/min ( ft/min)

- Wing loading: kg/m² ( lb/ft²)

- Thrust/weight: or

- Power/mass:

See also

|

Lists of Aircraft | Aircraft manufacturers | Aircraft engines | Aircraft engine manufacturers Airports | Airlines | Air forces | Aircraft weapons | Missiles | Timeline of aviation |