Metropolis (1927 movie)

|

|

Metropolis-new-tower-of-babel.jpg

Metropolis is a science fiction film produced in Germany set in a futuristic urban dystopia. Released in 1927, it is a black and white silent film directed by Austrian Fritz Lang and was the most expensive silent film of that time, costing 7 million Mark (equivalent to around $200 million today) [1] (http://members.fortunecity.com/roogulator/sf/metropolis.htm).

The screenplay was written in 1924 by Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou and novelized in 1926 by von Harbou.

| Contents |

Plot

Note : There are multiple versions of Metropolis. The original German version remained unseen for many decades. Of this version a quarter of the footage is believed to be permanently lost. The US version shortened and re-written by Channing Pollock is the most commonly known and discussed.

The film is set in the year 2026, in the extraordinary Gothic skyscrapers of a corporate city-state, the Metropolis of the title. Society has been divided into two rigid groups: one of planners or thinkers, who live high above the earth in luxury, and another of workers who live underground toiling to sustain the lives of the privileged. The city is run by Johhan 'Joh' Fredersen (Alfred Abel).

The beautiful and evangelical figure Maria (Brigitte Helm) takes up the cause of the workers. She advises the desperate workers not to start a revolution, and instead wait for the arrival of "The Mediator", who, she says, will unite the two halves of society. The son of Fredersen, Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), becomes infatuated with Maria, and descends into the working underworld. In the underworld, he experiences first-hand the toiling lifestyle of the workers, and observes the casual attitude of their employers (he is disgusted after seeing an explosion at the "M-Machine", when the employers bring in new workers to keep the machine running before taking care of the men wounded or killed in the accident). Shocked at the working conditions, he joins her cause. Meanwhile his father Fredersen learns of the existence of The Robot built by the scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) (Rotwang wanted to give the Robot the appearance of Fredersen's dead wife Hel) and orders Rotwang to give the Robot Maria's appearance. By doing so he wants to spread disorder among the workers what would give him the pretext to carry out a retaliatory strike against the workers.

The real Maria is imprisoned in Rotwang's house in Metropolis, whilst the robot Maria becomes an exotic dancer in the city's nightclubs, fomenting discord amongst the rich young men of Metropolis. The workers are encouraged by the robot Maria into a full-scale rebellion, and destroy the "Heart Machine", the power station of the city. However, the destruction of the machine leads to the city's reservoirs overfilling, which floods the workers' underground city and seemingly drowns their children, who were left behind in the riot. When the workers realise this, they attack out into the gridlocked and confused upper city, foreshadowing the "destruction of the enemy in the citadel" ending still seen in films. The crowd breaks into the city's entertainment district and capture the robot Maria, who they believe is responsible for drowning their children. They burn the robot at the stake, and when Freder sees this, he believes that it is the real Maria and despairs. However, Freder and the workers then realise that "Maria" is in fact a robot, and see the real Maria being chased by Rotwang along the battlements of the city's cathedral. Freder chases after Rotwang, resulting in a climatic scene in which Joh Fredersen watches in terror as his son struggles with Rotwang on the cathedral's roof. Rotwang falls to his death, and Maria and Freder return to the street, where Freder unites Joh and Grot, the workers' leader, fulfilling his role as the "Mediator".

Themes

1metropolis.JPG

The film contains a scene where Maria retells the story of the Tower of Babel from the Biblical book of Genesis, but in a way that connects it to the situation she and her fellow workers face. The scene changes from Maria to creative men of antiquity deciding to build a monument to the greatness of humanity, high enough to reach the heavens. Since they cannot build their monument by themselves, they concentrate workers to build it for them. The camera focuses on armies of workers unwillingly led to the construction site of the monument. They work hard but cannot understand the dreams of the Tower's designers, and the designers don't concern themselves with the fate of their workers. As the film explains "The dreams of a few, had turned to the curses of many". The workers revolt and in their fury destroy the monument. As the scene ends and the camera returns to Maria, only ruins remain of the Tower of Babel. This retelling is notable in keeping the theme of the lack of communication from the original story but placing it in the context of relations between social classes and omitting the presence of God.

The entire film is dominated by technology, with Lang using a mixture of both 1920s and futuristic devices. Much of the technology portrayed in the film is unexplained and appears bizarre - such as the enormous "M-Machine" and the "Heart Machine". Whilst the Heart Machine is implied to be the electrical power station of the city, the purpose of the M-Machine is never revealed, despite it playing a significant part in the film. While Freder is in the subterranean factories, he swaps places with an exhausted worker and takes over his seemingly pointless task - moving the dials of a gigantic clock-like device in accordance with flashing light bulbs. However, other machines featured in the film anticipate future inventions - Joh Fredersen's office has a television-like device which allows him to contact his overseers in the factories, and built into his desk is an electronic console which allows him to remotely open doors, etc. Also in his office is an automated electronic ticker-tape, with a weary and frustrated clerk constantly writing down the latest stock market prices. In the city itself, we see a mixture of futuristic monorails and airships combined with 1920s-style cars and aeroplanes.

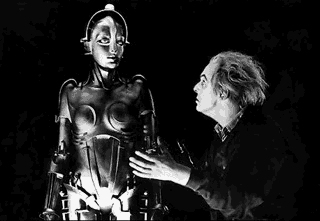

The ultimate expression of technology in the entire film is the female robot built by Rotwang, referred to as the "Maschinenmensch" or "Machine Human" although it is often translated as "Machine Man" in the US version. In the original German version Rotwang's creation is a reconstruction of his dead lover, a woman called Hel (a reference to Hel (goddess)). Both Rotwang and Joh Fredersen were in love with her. She chose Fredersen and became Freder's mother, though she died in childbirth. Rotwang, insanely jealous and angry about her death, creates the Maschinenmensch Hel. In the US version, The Machine Man is merely a fully functioning automaton which can be programmed to perform a variety of human tasks, whilst its appearance can be synthesised to resemble any human being. However, the Machine Man is sentient, and has its own agenda different to that of its creators. It performs the required task of fomenting revolution, but then becomes an exotic dancer, turning the young men of Metropolis against one another for its own entertainment. This anticipates the themes of many late-twentieth century films, in which seemingly unsentient machines gain consciousness and turn against the intentions of their creators.

Part of Fritz Lang's inspiration for the movie came during a trip to Manhattan, New York. He is quoted on the DVD of the Murnau Foundation version as saying "I saw the buildings like a vertical curtain, opalescent, and very light. Filling the back of the stage, hanging from a sinister sky, in order to dazzle, to diffuse, to hypnotize."

Visual effects

The film features special effects and set design that still impress modern audiences with their visual impact — glorious expressionist design and geometric forms. The effects expert, Eugen Schüfftan, created innovative visual displays widely acclaimed in following years.

Among the effects used are miniatures of the city, a camera on a swing, and most notably, the so-called Schüfftan process, later also used by Alfred Hitchcock.

The Maschinenmensch, also played by Brigitte Helm was created by Walter Schultze-Mittendorf. A chance discovery of a sample of "plastic wood" a kneadable substance made of wood allowed him to sculpt the costume like a suit of armour over a plaster cast of the actress. Painted a mix of silver and bronze it helped create some of the most memorable moments on film. Helm suffered greatly during filming these scenes, wearing this rigid and uncomfortable costume. But Fritz Lang insisted on her playing the part, even if nobody would know it was her.

"Disassembly" and restoration

Metropolis2002DVDcover.jpg

On January 10, 1927 the film premiered in Berlin, with moderate success. In the United States, the movie was shown in a version edited by the American playwright Channing Pollock, who almost completely obscured the original plot, considered too controversial by the American distributors, and is considerably shortened. In Germany, a version similar to Pollock's was shown on August 5. Only copies of these versions—mostly considered as badly-edited—remain today.

Several restored versions (all of them missing footage) were released in the 1980s and 1990s, running for around 90 minutes.

In 1984, a new restoration and edit of the film was compiled by Giorgio Moroder, a music producer who specialized in pop-rock soundtracks for motion pictures. Moroder’s version of the film introduced a new modern rock-and-roll soundtrack for the film, as well as playing at 24 frames per second and integrating the captions into the film itself as subtitles. His version of the film is only 80 minutes in length. The “Moroder version” of Metropolis sparked heated debate among film buffs and fans, with outspoken critics and supporters of the film falling into equal camps. In the 1990s, the Club Foot Orchestra scored, performed, and recorded a new soundtrack for this version of the film.

Enno Patalas made an exhaustive attempt to restore the movie in 1986. This restoration was by that time the most accurate, thanks to the script and the musical score that had been discovered. The basis of Patalas' work was a copy in the Museum of Modern Art's collection.

The F.W. Murnau Foundation released a 118-minute, digitally restored version in 2002. It included title cards describing the action in the missing sequences and, again, the original music score. (It is believed that the original film was over 210 minutes.)

Most silent films, including Metropolis, were shot at speeds of between 16 and 20 frames per second, but the digitally restored version with soundtrack plays at the standard sound speed of 24 frames per second (25 on PAL and SECAM videos and DVDs), which often makes the action look unnaturally fast. The reason for the decision to show the film at this speed is not clear. In the 1970s the BBC prepared a version with electronic sound that ran at 18 frames per second and consequently had much more realistic-looking movement.

Political significance

Metropolis's theme is connected with both Fascist or Socialist - the most powerful political ideologies of that time in Europe. The idea of the film is that the workers are oppressed, and their leader is Maria. In order to destroy the workers, Freder sends robot who, disguised as Maria, leads the workers to destroy the dam and flood their village. Some interpret this as an Anti-Communist message, claiming that the Communists, by calling the workers to revolt are leading them to destruction. Maria repeatedly claims that what the workers need is a Mediator. Some interpret this as a reference to Corporate Statism the fascist concept where the ruling party acts as a mediator between the workers and the capitalists.

There is a rumour that Metropolis was one of the favorite films of Adolf Hitler and he tried to get Fritz Lang to make propaganda films for him. Allegedly Hitler's interpretation of the film saw the oppressors, specifically Fredersen, as being Jewish. This rumour has its routs in a passage in Siegfried Kracauer's book From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film

- Joseph Goebbels, the head of the Nazi party's Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda organization became interested in Metropolis, too. According to Lang, " he told me that, many years before, he and the Führer had seen my picture Metropolis in a small town, and Hitler had said at that time that he wanted me to make Nazi pictures" (Kracauer 164).

Most of Metropolis was filmed at UFA studios at Babelsberg and was enormously expensive. Some sources put the total cost at four times the original budget. The official costs accumulated to 7 million mark (about 200 million dollars now). These cost overruns were a contributing factor in UFA's financial instability through the late 1920s and its subsequent appropriation by Nazi interests.

Influence

This film has influenced many science fiction movies to the present day, including Blade Runner, Dark City, and The Matrix. The "Tower of Babel" structure is a key element in several films; in turn, Metropolis's tower appears to derive from Hans Poelzig's stocky, polygonal, modernistic water tower built in Posen in 1911. But the earliest films to be influenced were Just Imagine of 1930, which also featured a city with much air transport among and between skyscrapers connected by bridges, and Vultan's city in the first Flash Gordon serial of 1936, which had a sweatshop controlled by an operator who moved the needle of a huge dial while standing up.

Rotwang, the film's mad scientist, has lost his right hand and has replaced it with a black prosthesis. In the film Dr. Strangelove, directed by Stanley Kubrick and first released on January 29, 1964, the German mad scientist Dr. Strangelove wears a black glove on his right hand, a hand which he cannot consciously control. This is considered to be a tribute to the earlier film.

A similar theme shows up in George Lucas' famous Star Wars films, in which the heroes, Anakin Skywalker and his son Luke, lose their right hands in combat and each has it replaced with a prosthesis, wearing a black glove over the robotic hand. He later discovers that his father also has a robotic right hand, and the lack of the right hand is an important symbolism in the films. This was influenced as well by Jungian mythological archetypes, via George Lucas' friend, the psychologist, Joseph Campbell. C-3PO's appearance is that of a male (or perhaps genderless) version of Rotwang's robot.

Yet another example of the missing right hand archetype is Philip K. Dick's masterpiece, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, considered by many to be his best book. An important element of the story is that Palmer Eldritch, the antagonist, possesses a robotic right arm, as well as artificial eyes, and a deformed jaw.

Many of the scenes involving Rotwang seem to echo (or prophesy, it is not entirely clear) the many film adaptations of Mary Shelley's science-ficton novel Frankenstein, particularly the part where the Machine-Man is created.

The ending of the film likewise is a piece of much imitated classic cinema. The climactic struggle between Rotwang and Freder over the life of Maria is strikingly similar to the many early film adaptations of Victor Hugo's novel Hunchback of Notre Dame.

A musical theater adaption was staged in London in 1989. See Metropolis (musical).

An anime adaptation of Osamu Tezuka's manga Metropolis was released in the U.S. in 2002. See Metropolis (2001 movie). The anime series Big O seems to draw inspiration from Metropolis as well.

Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow contains several references to Fritz Lang's film, mostly voiced through the German rocket scientists and engineers who comprise a large part of its cast.

The film has inspired or been included in several music videos, including Madonna's "Express Yourself" and Queen's "Radio Ga Ga".

Jeff Mills released an album named Metropolis inspired by the film in 2001.

External links

- Template:Imdb title

- The official site of the new restoration (http://www.kino.com/metropolis/)

- Metropolis web site (http://www.persocom.com.br/brasilia/metropo.htm)

- Metropolis page (http://www.unesco.org/webworld/mdm/2001/eng/germany/metropolis/intro.html) at the UNESCO Memory of the World Registerde:Metropolis (Film)

es:Metrópolis (Fritz Lang) fr:Metropolis (film, 1927) it:Metropolis (film 1927) mk:Метрополис pt:Metrópolis (cinema) sv:Metropolis (film)