Blade Runner

|

|

Template:Infobox Movie Blade Runner is a science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott and released in 1982, depicting a dark, dystopic vision of Los Angeles in November 2019. The screenplay, written by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples, is loosely based on the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick. The film was designed in part by Syd Mead and has a soundtrack by Vangelis. Harrison Ford stars as LAPD detective Rick Deckard, with co-stars Rutger Hauer, Darryl Hannah, Sean Young, Brion James, William Sanderson, and Edward James Olmos.

The film describes a future in which genetically manufactured beings called replicants are used for dangerous and degrading work in Earth's "off-world colonies." Built by the Tyrell Corporation to be 'more human than human', the Nexus-6 generation appear physically identical to humans and have superior strength and agility while lacking comparable emotional responses and empathy. Replicants became illegal on Earth after a bloody mutiny. Specialist police units hunt replicants on Earth. These units—Blade Runners—"retire" (kill) escaped replicants. With a particularly brutal and cunning group of replicants on the loose in Los Angeles, a reluctant Deckard is recalled from semi-retirement for some of 'the old Blade Runner magic'.

Blade Runner had a mixed reception as it languished in North American theaters but achieved success overseas. Despite the lack of immediate success, it was adored by fans and academia and gained cult classic status. The film prefigured dominant issues decades into the future through the lens of film noir, a cinematic technique from decades past. In only a few years it gained such great popularity as a video rental that it was one of the first DVDs to be released. It has been widely hailed as a modern classic in league with 2001: A Space Odyssey and praised as being as influential among science fiction films as Metropolis. Blade Runner also brought author Philip K. Dick to the attention of Hollywood, and numerous films have since been based on his literature, the most recent of which is A Scanner Darkly.

| Contents [hide] |

Creators

Based loosely on the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick. Although he was able to watch a pre-release screening, Dick died before Blade Runner went into general release. The original screenplay was written by Hampton Fancher and attracted the interest of producer Michael Deeley. Deeley secured financing for the film from a range of sources (which later proved to be a problem) and convinced director Ridley Scott to create his first American film, but Scott was unhappy with the script and had David Peoples do a re-write.

The term "Blade Runner" comes originally from Alan E. Nourse's 1974 novel The Bladerunner, in which the protagonist is a smuggler of black-market surgical implements. Nourse's book inspired a script treatment in the form of a novel, William S. Burroughs' Bladerunner, A Movie, but apart from the title, neither Nourse's novel nor Burroughs' had any influence on Ridley Scott's film. Hampton Fancher happened upon a copy of Bladerunner, A Movie while Scott was looking for a snappier title for his film; Scott liked the term and obtained the rights to the title (but not any aspect of the plot). Some editions of Burroughs' book use the spacing Blade Runner.

Blade Runner echoes several earlier works, among them Fritz Lang's silent film Metropolis; not only are visual similarities numerous, but so are the many issues they explore.Template:Ref Scott credits Edward Hopper's painting Nighthawks with helping set the visual style and mood for Blade Runner. Scott contracted Syd Mead as a conceptual artist, both of whom were influenced by a French comic magazine Métal Hurlant (Heavy Metal) illustrated by Moebius.Template:Ref Lawrence G. Paull (production designer) and David Snyder (art director) were responsible for converting Scott's and Mead's sketches into reality. Jim Burns worked briefly on the design of the Spinner flying cars. The special effects for the film were supervised by Douglas Trumbull and Richard Yuricich.

Prior to principal photography Paul M. Sammon was commissioned by Cinefantastique magazine to do a special article on the making of Blade Runner. His detailed observations and research later became a book called Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner, which is also called the Blade Runner Bible by the cult following of the film. The book outlines not only the evolution of Blade Runner but the politics and difficulties on-set; particularly on Scott's expectations (coming from Britain) of his first American crew. Also, his directing style with actors created friction with the cast and likely contributed to Ford's subsequent reluctance to discuss the film.

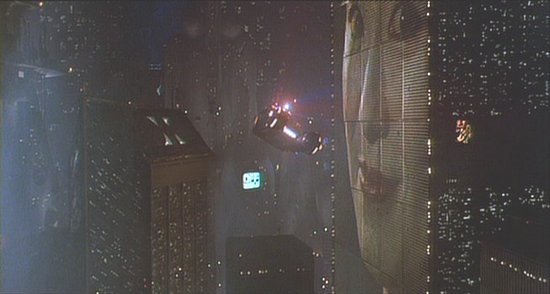

A police spinner flies through the advertising laden skyscrapers of LA 2019. |

Influence and Awards

Initially avoided by North American audiences it was popular internationally and has become a cult classic. The movie's dark cyberpunk style and futuristic design have served as a benchmark and inspired many subsequent science fiction films, including Batman, Robocop, The Fifth Element, Ghost in the Shell, and The Matrix. Even the Star Wars prequels have paid homage to Blade Runner in their special effects sequences.Template:Ref

The film is often thought to have inspired William Gibson's Neuromancer. Gibson has said in interviews that he was already writing Neuromancer when Blade Runner was released, and was actually inspired by the implied background of the film Alien.

The film arguably marks the introduction of the cyberpunk genre into popular culture. Blade Runner continues to reflect modern trends and concerns, and an increasing number consider it one of the greatest science fiction films of all time.Template:RefTemplate:Ref The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 1993. Its memorable quotations and soundtrack have made it the most musically-sampled film in the 20th century.Template:Ref

Blade Runner has been nominated for many awards and has won the following accolades:

| Year | Award | Category - Recipient(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award | Best Cinematography - Jordan Cronenweth |

| 1983 | BAFTA Film Award | Best Cinematography - Jordan Cronenweth |

| Best Costume Design - Charles Knode, Michael Kaplan | ||

| Best Production Design/Art Direction - Lawrence G. Paull | ||

| 1983 | Hugo Award | Best Dramatic Presentation |

| 1983 | London Critics Circle Film Awards - Special Achievement Award | Lawrence G. Paull, Douglas Trumbull, Syd Mead - For their visual concept (technical prize). |

Synopsis

The plot begins in one of the Tyrell Corporation pyramids with Holden (a Blade Runner) conducting a Voight-Kampff empathy test (to uncover replicants) with a new employee (Leon) who ends up shooting Holden twice.

In downtown Los Angeles, Deckard (a retired Blade Runner) is forced to come with Gaff (another Blade Runner) to see his old boss Bryant. Upon arriving at police headquarters Bryant tells Deckard that there are escaped replicants in Los Angeles. Deckard takes the case after a thinly-veiled threat from Bryant, and he is briefed on the replicants: Roy (the leader), Leon, Zhora and Pris.

BladeRunner_Sun.jpg

Deckard is sent to the Tyrell Corporation to do a Voight-Kampff test on a Nexus-6 to ensure it works. Tyrell requests the test be done on a human before he provides a replicant subject and he volunteers Rachael to take the test. After an extensive test Deckard discovers Rachael is an experimental replicant who has implanted memories to help cope with emotions. Deckard and Gaff then go to Leon's apartment where Deckard finds photos and a scale in the bathtub.

Meanwhile, Roy and Leon pay a visit to Chew – a genetic eye designer who creates eyes for Nexus-6 replicants. Roy intimidates Chew in directing them to J.F. Sebastian, who can lead them to Tyrell. While this is happening Rachael visits Deckard at his apartment to prove her humanity, but leaves in tears upon hearing her memories are artificial.

J.F. Sebastian (a genetic designer working for Tyrell) is returning home when he encounters Pris, who manipulates her way into his apartment. During this time Deckard heads down to Animoid Row and discovers the scale from the bathtub is from an artificial snake designed by Abdul-Ben Hassan. Hassan directs Deckard to Taffy Lewis's bar where he sees Zhora perform with a snake. Deckard talks his way into her dressing room, but she attacks him and runs out into the crowded streets. Deckard hunts her down and shoots her in the back. Gaff and Bryant show up on the scene, where Bryant informs Deckard that Rachael has disappeared and needs to be "retired".

As Bryant and Gaff leave, Deckard spots Rachael in the distance. However, Leon surprises Deckard and knocks his gun to the ground before beating him senseless in an alleyway. Just as he is about to kill Deckard, Rachael shoots Leon in the head. They go back to Deckard's apartment and fall in love.

BladeRunner_Roy_Tyrell.jpg

Meanwhile, Roy has arrived at Sebastian's apartment and with Pris' charms they convince Sebastian to take Roy to see Tyrell. Once there Roy demands an extension to his lifespan, then requests absolution for his sins; upon receiving neither, he kills Tyrell and Sebastian.

Bryant calls Deckard about the murders and orders him to check out Sebastian's apartment. Deckard enters the apartment and is surprised by Pris but manages to shoot her after a struggle. Roy returns moments later trapping Deckard in the apartment. Finding her body Roy mourns for Pris and then pursues Deckard in revenge. Fleeing the murderous Roy, Deckard drops his gun and then is forced to jump across the rooftop to another building; he doesn't quite make the distance, and is left desperately hanging from the edge. Just as Deckard looses his grip, Roy grabs Deckard's wrist and saves his life. Soon after Roy peacefully loses his life as his four-year lifespan comes to an end.

Deckard returns to his apartment and cautiously enters when he sees the door is ajar. He finds Rachael alive and as they leave Deckard comes across an origami calling card left by Gaff; he has allowed them to escape, and they depart toward an uncertain future together.

Versions

Six versions of the film exist but only two are widely known and seen:

- The original 1982 international cut, which included more graphic violence than the U.S. theatrical release, and which was released on VHS and on Criterion Collection Laserdisc.

- The U.S. theatrical version, also called the domestic cut.

- Two workprint versions, shown only as audience test previews and occasionally at film festivals; one of these was distributed in 1991, as a Director's Cut without Scott's approval.

- The Ridley Scott-approved 1992 Director's Cut, prompted by the unauthorized 1991 release, is to date the only version released on DVD.

- The broadcast version, edited for profanity.

BladeRunner_Unicorn1.jpg

In the 1992 Director's Cut, the ending was dramatically altered, with the overall effect of the changes intended to make Deckard's humanity, and his and Rachael's fate, ambiguous. Scott removed Deckard's explanatory voice-over, and two additional scenes were added.

The first depicts Deckard's dream of a unicorn running through a forest while he dozes drunkenly at his piano. The footage, originally thought to have been filmed for Ridley Scott's Legend, was recently confirmed as original 1982 footage removed before the initial theatrical release.

The second was a small scene added to the ending, in which Deckard finds a small origami unicorn, presumably made by Gaff, on the ground by the elevator as he leaves with Rachael. This edition ends at the moment when the elevator doors in Deckard's building close, deleting a scene with Deckard and Rachael driving into the mountains to safety.

Finally, the background visuals of the end credits (a concave-lens aerial shot of a verdant pine forest rushing by, originally filmed for Stanley Kubrick's The Shining) were replaced by a simple black background. Scott has since complained that time and money constraints kept him from retooling the film in a satisfactory manner, and that he's never felt entirely comfortable with it as his definitive "Director's Cut" of the film.

Partly as the result of those complaints, Scott was invited back in mid 2000 to help put together a final and definitive version of the film, which was completed in early 2002. During the process, a new digital print of the film was created from the original negatives, special effects were updated and cleaned, and the score was remastered in 5.1 Dolby Digital surround sound. Unlike the rushed 1992 Director's Cut, Scott personally oversaw the new cut. The Special Edition DVD was slated for a Christmas time 2002 release, and is rumored to be a three-disc set including the full international theatrical cut, the 1992 director's cut, and the newly-enhanced version, as well as deleted scenes, extensive cast and crew interviews, and a BBC documentary.

However, the "Special Edition" release was delayed indefinitely by Warner Brothers after legal disputes began with the film's original bond guarantors (specifically Jerry Perenchio), who were ceded ownership of the film when the shooting ran over budget from $21.5 to $28 million. As of 2005, the legal issues remain unresolved. Warner Bros. remains the film's distributor and is authorized to release the 1992 Director's Cut on video. Warner Bros. also acts as distributor for the original 1982 theatrical version, which remains in circulation on television (albeit edited for the medium).

Themes

Main article: Themes in Blade Runner

Blade Runner operates on an unusually rich number of dramatic levels. As with much of cyberpunk, it owes a large debt to film noir, containing such conventions as the femme fatale, a Chandleresque first-person narration (removed in later versions), and the questionable moral outlook of the Hero – extended here even to include the humanity of the hero, as well as the usual dark and shadowy cinematography.

It is one of the most literate science fiction films, both thematically – enfolding the philosophy of religion and moral implications of the increasing human mastery of genetic engineering, within the context of classical Greek drama and its notions of hubrisTemplate:Ref – and linguistically, drawing on the poetry of William Blake and the Bible. Blade Runner also features a chess game based on the famous Immortal Game of 1851. (Although the king and queen are interposed on Tyrell's side. A grandmaster would never make the 3 moves necessary to achieve this position.)

Film critics

When the film was released film critics were polarized. Some felt the story had taken a back seat to special effects and that it was not the action/adventure the studio had advertised. Others acclaimed its complexity and predicted it would stand the test of time.Template:Ref

BladeRunner_Deckard_and_Rachael.jpg

A general criticism was its slow pacing takes away from other elements;Template:Ref one film critic went so far as to call it "Blade Crawler."Template:Ref Roger Ebert praised Blade Runner's visuals but found the human story a little thin. Ebert says Tyrell's unconvincing character and the apparent lack of security measures allowing Roy to murder Tyrell are problems. Also he believes the relationship between Deckard and Rachael seem "to exist more for the plot than for them."Template:Ref

It could be argued the strong visuals serve to create a dehumanized world where human elements stand out. Furthermore the relationship between Deckard and Rachael could be essential in reaffirming their respective humanity.Template:Ref

Soundtracks

Main article: Blade Runner (soundtracks)

Vangelis created a soundtrack that combined classic composition and futuristic synthesizers. It was nominated for several awards but not officially released for over a decade. In the interim the New American Orchestra was contracted in 1982 to release the official soundtrack, which bore little resemblance to the original. Also in 1982 a bootleg tape was available and became popular given the delays with an official Vangelis release. In 1989 a Vangelis "Themes" Collection LP had some tracks from the film included, and in 1993 "Off World Music, Ltd." created a bootleg CD that was more comprehensive than Vangelis' official CD in 1994. Then in 2005 – Blade Runner (Esper Edition) – a definitive 2 CD bootleg soundtrack was compiled.

Literature, TV and games

BladeRunner_PC_Game_(Front_Cover).jpg

Three more Blade Runner novels, which are sequels to the film rather than the book, have been written by Philip K. Dick's friend K. W. Jeter:

- Blade Runner 2: The Edge of Human (1995)

- Blade Runner 3: Replicant Night (1996)

- Blade Runner 4: Eye and Talon (2000)

There are also two computer games based on the film, one for Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum by CRL Group PLC (1985) and another action adventure PC game by Westwood Studios (1997). The latter game featured new characters and branching storylines based on the Blade Runner world, coupled with voicework from some of the original cast from the film. A prototype board game was also created in California (1982) that had gameplay similar to Scotland Yard.

References

- Template:Note Bukatman, Scott. (1997) Blade Runner: BFI Modern Classics. ISBN 0851706231

- Template:Note Sammon, Paul. (1996) Future Noir: the Making of Blade Runner. ISBN 0061053147

- Template:Note Brinkley, Aaron. Gunn, R. (2002) The Blade Runner / Star Wars References (http://www.bladezone.com/contents/film/tie-ins/star-wars/)

- Template:Note Jha, Alok. Rogers, S. Rutherford, A. (2004) Guardian.co.uk – Our expert panel votes for the top 10 sci-fi films (http://www.guardian.co.uk/life/feature/story/0,13026,1290561,00.html)

- Template:Note Netrunner. (2005) BRmovie.com – Top 100s and Reviews (http://www.brmovie.com/BR_Views.htm)

- Template:Note Cigéhn, Peter. (2004) Sloth.org – The Top 1118 Sample Sources (http://web.archive.org/web/20041013041105/www.sloth.org/samples-bin/samples/source?summary)

- Template:Note Sammon, Paul. (1996) Future Noir: the Making of Blade Runner. ISBN 0061053147

- Template:Note Hicks, Chris. (1992) DeseretNews.com – Review of Blade Runner (http://deseretnews.com/movies/view/0,1257,200,00.html)

- Template:Note Flynn, John. (2003) Towson.edu – Blade Runner Retrospective (http://www.towson.edu/~flynn/br.htm)

- Template:Note Ebert, Roger. (1992) RogerEbert.com – Review of Blade Runner (http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19920911/REVIEWS/209110301/1023)

- Template:Note Rutledge, Sean M. (2000) CandidCritic.com – Review of Blade Runner (http://www.candidcritic.com/blade_runner.htm)

- Template:Note Kerman, Judith. (1991) Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner" and Philip K. Dick's "Do Android's Dream of Electric Sheep?" ISBN 0879725109

See also

- Films that have been considered the greatest ever

- Blade Runner (videogame)

- Bradbury Building - the setting for J.F. Sebastian's apartment.

- Ennis-Brown_House - the setting for Deckard's apartment.

- Voight-Kampff machine

- Dystopia

- Postmodernism or Postmodernity

- Soldier (movie)

- List of movies

- List of actors

- List of directors

- List of documentaries

- List of Hollywood movie studios

External links

- Template:Imdb title

- BRMovie.com (http://www.brmovie.com/) - alt.fan.blade-runner site

- Special Edition News Page (http://www.brmovie.com/BR_Special_Edition.htm)

- Petition: Special Edition DVD (http://www.petitiononline.com/B26354/petition.html) - Petition to Release Special Edition DVD

- 2019: Off-World (http://scribble.com/uwi/br/) - One of the first Blade Runner fan sites

- BladeZone (http://bladezone.com/) - The Online Blade Runner Fan Club & Museum

- Rotten Tomatoes: Review Collection (http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/blade_runner_the_directors_cut/)ca:Blade Runner

de:Blade Runner es:Blade Runner fr:Blade Runner (film) ja:ブレードランナー pl:Łowca androidów sv:Blade Runner fi:Blade Runner zh:银翼杀手