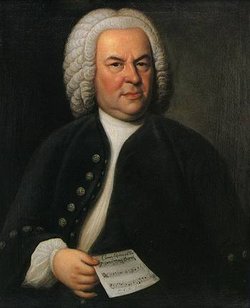

Johann Sebastian Bach

|

|

Johann Sebastian Bach (March 21, 1685 (O.S.) – July 28, 1750 (N.S.))[1] (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#fn_birthanddeath) was a German composer and organist of the Baroque period, and is universally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time. His works, noted for their intellectual depth, technical command, and artistic beauty, have provided inspiration to nearly every musician in the European tradition, from Mozart to Schoenberg. Some of his most famous works include the Brandenburg Concertos, The Well-Tempered Clavier, the Mass in B Minor and the St. Matthew Passion.

Bach was a part of perhaps the most amazing musical family in history. For over two hundred years they were a family of musicians and composers. Bach's father, uncles and elder brother were all professional musicians, as well as numerous other more distant relatives, while his sons Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Johann Christian Bach became important musicians and composers in their own right. (See Bach family.)

| Contents |

Biography

Formative years

J. S. Bach was born in Eisenach, Germany[2] (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#fn_birthplace) in 1685. His father, Johann Ambrosius Bach, was the town piper in Eisenach, a post that entailed organizing all the secular music in town as well as participating in church music at the direction of the church organist; his uncles were also all professional musicians ranging from church organists and court chamber musicians to composers, although Bach would later surpass them all in his art. In an era when sons were expected to be apprentices to their fathers, we can assume J. S. Bach began copying music and playing various instruments at an early age.

Bach's mother died in 1694, and his father died suddenly, in February of 1695, when J. S. Bach was not quite ten. Bach moved in with his older brother Johann Christoph Bach, who was the organist of Ohrdruf. While in his brother's house, Bach continued copying, studying, and playing music. According to one popular legend of the young composer's curiosity, late one night, when the house was asleep, he retrieved a manuscript (which may have been a collection of works by Johann Christoph's former mentor, Johann Pachelbel) from his brother's music cabinet and began to copy it by the moonlight. This went on nightly until Johann Christoph heard the young Sebastian playing some of the distinctive tunes from his private library, at which point the elder brother demanded to know how Sebastian had come to learn them.

It was at Ohrdruf that Bach began to learn about organ building. The Ohrdruf church's instrument, it seems, was in constant need of minor repairs, and he was often sent into the belly of the old organ to tighten, adjust, or replace various parts. The church organ, with its moving bellows, manifold stops, and complicated mechanism, was the most complex machine in any European town. This practical experience with the innards of the instrument would provide a unique counterpoint to his unequalled skill in playing it; Bach was equally at home talking with organ builders and with performers.

While in school and as a young man, Bach's curiosity compelled him to seek out great organists of Germany such as Georg Böhm, Dietrich Buxtehude and Johann Adam Reinken, often taking journeys of considerable length to hear them play. He was also influenced by the work of Nicholas Bruhns. Shortly after graduation (Bach completed Latin school when he was 18, an impressive accomplishment in his day, especially considering that he was the first in his family to finish school), Bach took a post as organist at Arnstadt in 1703. He apparently felt cramped in the small town and began to seek his fortune elsewhere. Owing to his virtuosity, he was soon offered a more lucrative organist post in Mühlhausen. Some of Bach's earliest extant compositions date to this period (including, according to some scholars, his famous Toccata and Fugue in D Minor), but much of the music Bach wrote during this time has been lost.

Professional life

Still not content as organist of Mühlhausen, in 1708 Bach took a position as court organist and concert master at the ducal court in Weimar. Here he had opportunity not only to play the organ but also to compose for it and play a more varied repertoire of concert music with the duke's ensemble. A devotee of contrapuntal music, Bach's steady output of fugues begins in Weimar. The best known example of his fugal writing is probably The Well-Tempered Clavier, which comprises 48 preludes and fugues, one pair for each major and minor key, a monumental work not only for its masterful use of counterpoint but also for exploring, for the first time, the full glory of keys — and the means of expression made possible by their slight differences from each other — available to keyboard musicians when their instruments are tuned according to Andreas Werckmeister's system of well temperament or similar system.

Also during his tenure at Weimar, Bach began work on the Orgelbüchlein for his son Wilhelm Friedemann. This "little book" of organ music contains traditional Lutheran church hymns harmonized by Bach and compiled in a way to be instructive to organ students. This incomplete work introduces two major themes into Bach's corpus: firstly, his dedication to teaching, and secondly, his love of the traditional chorale as a form and source of inspiration. Bach's dedication to teaching is especially remarkable. There was hardly any period in his life when he did not have a full-time apprentice studying with him, and there were always numerous private students studying in Bach's house, including such 18th century notables as Johann Friedrich Agricola. Still today, students of nearly every instrument encounter Bach's works early and revisit him throughout their careers.

Sensing increasing political tensions in the ducal court of Weimar, Bach began once again to search out a more stable job conducive to his musical interests. Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen hired Bach to serve as his Kapellmeister (director of music). Prince Leopold, himself a musician, appreciated Bach's talents, compensated him well, and gave him considerable latitude in composing and performing. However, the prince was Calvinist and did not use elaborate music in his worship, so most of Bach's work from this period is secular in nature. The Brandenburg concerti, as well as many other instrumental works, including the Six Suites for Solo Cello, the Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, and the Orchestral Suites, date from this period.

In 1723, J. S. Bach was appointed Cantor and Musical Director of the Thomaskirche, Leipzig.[3] (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#fn_cantor_thomaskirche) This post required him not only to instruct the students of the St. Thomas school (Thomasschule) in singing but also to provide weekly music at the two main churches in Leipzig. Bach endeavoured to compose a new church piece, or cantata, every week. This challenging schedule, which amounted to writing an hour's worth of music every week, in addition to his more menial duties at the school, produced some of his best music, most of which has been preserved. Most of the cantatas from this period expound upon the Sunday readings from the Bible for the week in which they were originally performed; some were written using traditional church hymns, such as Wachet auf! Ruft uns die Stimme and Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, as inspiration for the music.

On holy days such as Christmas, Good Friday, and Easter, Bach produced cantatas of particular brilliance, most notably the Magnificat in D for Christmas and St. Matthew Passion for Good Friday. The composer himself considered the monumental St. Matthew Passion among his greatest masterpieces; in his correspondence, he referred to it as his "great Passion" and carefully prepared a calligraphic manuscript of the work, which required every available musician in town for its performance. Bach's representation of the essence and message of Christianity in his religious music is considered by many to be so powerful and beautiful that in Germany he is sometimes referred to as the Fifth Evangelist.

Family life

Morning_prayers_in_the_family_of_Sebastian_Bach.jpg

Bach married his second cousin, Maria Barbara Bach, on October 17, 1707 in Dornheim after receiving an inheritance of 50 gulden.[4] (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#fn_Maria_Barbara_marriage) They had 7 children, 4 of whom survived to adulthood. Little is known of Maria Barbara. She died suddenly on July 7, 1720 while Bach was travelling with Prince Leopold.

While at Cöthen, Bach met Anna Magdalena Wilcke, a young soprano. They married on December 3, 1721. Despite the age difference (she was 17 years his junior), the couple seem to have had a very happy marriage. Anna supported Johann's composing (many final scores are in her hand) while he encouraged her singing. Together they had 13 children.

All the Bach children were musically inclined, which must have given the ageing composer much pride. His sons Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johann Gottfried Bernhard Bach, Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach, Johann Christian Bach, and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach all became accomplished musicians, with J.C. Bach greatly influencing the early work of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Although the barriers to women having professional careers were great, all of Bach's daughters most likely sang and possibly played in their father's ensembles. The only one of the Bach daughters to marry, Elisabeth Juliana Friederica, chose as her husband Bach's student Johann Christoph Altnikol. Most of the music we have from Bach was passed on through his children, who preserved much of what C.P.E. Bach called the "Old Bach Archive" after his father's death.

At Leipzig, Bach seems to have fit in amongst the faculty of the university, with many professors standing as god-parents for his children, and some of the university's men of letters and theology providing many of the librettos for his cantatas. In this last capacity Bach enjoyed a particularly fruitful relationship with the poet Picander. Sebastian and Anna Magdalena also welcomed friends, family, and fellow musicians from all over Germany into their home; court musicians at Dresden and Berlin as well as musicians including George Philipp Telemann (one of C.P.E.'s godfathers) made frequent visits to Bach's house and may have kept up frequent correspondence with him. Interestingly, Georg Friedrich Händel, who was born in Halle (appr. 50 km from Leipzig) in the same year as Bach, made several trips to Germany, but Bach was unable to meet him, a fact he regretted.

Jsbach.jpg

Later life

Having spent much of the 1720s composing weekly cantatas, Bach assembled a sizeable repertoire of church music that, with minor revisions and a few additions, allowed him to continue performing impressive Sunday music programmes while pursuing other interests in secular music, both vocal and instrumental. Many of these later works were collaborations with Leipzig's Collegium Musicum, but some were increasingly introspective and abstract compositional masterpieces that represent the pinnacle of Bach's art. These erudite works start with the four volumes of his Clavier-Übung ("Keyboard Practice") a set of keyboard works to inspire and challenge organists and lovers of music that includes the Six Partitas for Keyboard (Vol. I), the Italian Concerto, the French Overture (Vol. II), and the Goldberg variations (Vol. IV).

At the same time, Bach wrote a complete Mass in B Minor, which incorporated newly composed movements with portions from earlier works. Although the mass was never performed during the composer's lifetime, it is considered to be among the greatest of his choral works.

In 1747 Bach went to Frederick the Great's court in Potsdam, where the king played a theme for Bach and challenged him to improvise a fugue based on his theme. Bach improvised a three-part fugue on Frederick's pianoforte, then a novelty, and later presented the king with a Musical Offering which consists of fugues, canons and a trio based on the "royal theme". Its six part fugue includes a slightly altered subject more suitable for extensive elaboration. Frederick's original theme begins in triads and then ends with a chromatic descent more characteristic of the rococo style. However, Bach used chromatic descent in many other works, famously the Fugue in G minor from Sonata No. 1 for Unaccompanied Violin and in the romanesca bass line in his monumental Chaconne in D minor from Solo Violin Partita No. 2 (Bach).

Bach's famous unfinished work, The Art of Fugue, was written months before his death. It consists of eighteen complex fugues and canons based on a simple theme, the last quadruple fugue of which stopped unexpectedly after the composer introduced a third theme, a play on his name. A magnum opus of thematic transformation and contrapuntal devices, this work is often cited as the summation of polyphonic techniques.

The final work Bach completed was a chorale prelude for organ dictated to his son-in-law, Altnikol, from his deathbed. Entitled Vor Deinen Thron Tret Ich Hiermit (Before Thy Throne I Now Appear), when the notes of the final cadence are counted and mapped onto the Roman alphabet, the word "BACH" is again found. The chorale is often played after the unfinished fourteenth fugue to conclude performances of The Art of Fugue.

Johann Sebastian Bach spent his last days in Leipzig and died there in 1750, at the age of 65. During his life he composed over 1,000 pieces.

Works

The BWV numbering system

- Main article: BWV

Johann Sebastian Bach's works are indexed and assigned BWV numbers, an initialism for "Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis", meaning "Bach Works Catalogue" in German. The catalogue, published in 1950, was compiled by Wolfgang Schmieder and the BWV numbers are sometimes referred to as Schmieder Numbers. A variant of this system uses S, instead of BWV, for Schmieder.

The catalogue is organised thematically rather than chronologically: BWV 1-222 are cantatas, BWV 225-248 the large-scale choral works, BWV 250-524 chorales and sacred songs, BWV 525-748 organ works, BWV 772-994 other keyboard works, BWV 995-1000 lute music, BWV 1001-1040 chamber music, BWV 1041-1071 orchestral music and BWV 1072-1126 canons and fugues. In compiling the catalogue Schmieder largely followed the Bach Gesellschaft Ausgabe, a comprehensive edition of the composer's works produced between 1850 and 1905.

For a list of works catalogued by BWV number, see List of compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Organ works

Bach was best known during his lifetime as an organist, organ consultant, and composer of organ works both in free genres (such as preludes, fantasias, and toccatas) and prescribed forms like the chorale prelude. Despite his lack of formal training as an organist, Bach established a reputation early on for his great creativity and ability to integrate aspects of several different national styles into his organ works. A decidedly North German influence was exerted by Georg Böhm, whom Bach came in contact with in Lüneburg, and Dietrich Buxtehude in Lübeck, whom the young organist visited in 1704 on an extended leave of absence from his job in Arnstadt. Around this time Bach also copied the works of numerous French and Italian composers in order to gain insights into their compositional languages, and later even arranged several violin concertos by Vivaldi and others for organ. His most productive period (1708-1714) saw not only the composition of several pairs of preludes and fugues and toccatas and fugues, but also the writing of the Orgelbüchlein ("Little Organ Book"), an unfinished collection of 49 short chorale preludes intended to demonstrate various compositional techniques that could be used in setting chorale tunes. After leaving Weimar, Bach's output for organ fell off, although his most well-known works (the six trio sonatas, the Clavierübung III of 1739, and the "Great Eighteen" chorales, revised very late in his life) were all composed after this time. Bach was also extensively engaged later in his life in consulting on various organ projects, testing newly-built organs, and dedicating organs in afternoon recitals.

Other keyboard works

Bach wrote many works for "clavier," usually understood to mean an unspecified keyboard. Although the piano ("Klavier" in German) was invented in Bach's lifetime, most scholars doubt he had one or intended any of his music for it. His keyboard works may have been intended for harpsichord or clavichord instead.

His best known keyboard works are the Two-part inventions and Three-part inventions (or "sinfonias"), probably intended for instructional purposes rather than concert use. He also wrote a set of English suites and a set of French suites, complex and difficult music based loosely on dance forms. He also wrote a number of other solo dances, suites, partitas, and the like. His best-known work is The Well-Tempered Clavier, a set of preludes and fugues in each of the twelve major and minor keys. The word "well-tempered" refers to the temperament in which the keyboard is tuned; tuning systems before Bach's time weren't flexible enough to allow compositions in all keys to be played without retuning. It is, however, uncertain what temperament he meant.

Chamber music

Bach wrote music for single instruments (in particular a set of sonatas and partitas for solo violin, unaccompanied, and a similar set for cello), duets, and other small ensembles. He wrote trio sonatas, solo sonatas (for a single instrument accompanied by continuo), and a large number of canons, mostly for unspecified instrumentation. The most significant examples of the latter are The Art of the Fugue and The Musical Offering.

Orchestral works

Bach's best-known orchestral works are the Brandenburg concertos, so named because he submitted them as a job audition for the Margrave of Brandenburg in 1721 (he didn't get the job). These works are examples of the concerto grosso genre. He also wrote a number of solo concertos for violin, harpsichord, and even two, three, and four harpsichords. He also wrote four Orchestral suites, a series of stylised dances for orchestra.

Vocal and choral works

Cantatas

Bach performed a cantata every Sunday at the Thomaskirche, on a theme corresponding to the lectionary readings of the week. Although he performed cantatas by other composers, he also composed at least three entire sets of cantatas, one for each Sunday and holiday of the church year, at Leipzig, in addition to those composed at Mühlhausen and Weimar. In total he wrote over 300 cantatas, of which only 195 survive.

His cantatas vary greatly in form and instrumentation. Some of them are only for a solo singer; some are single choruses; some are for grand orchestras, some only a few instruments. A very common format, however, includes a large opening chorus followed by one or more recitative-aria pairs for soloists (or duets), and a concluding chorale The recitative is part of the corresponding Bible reading for the week and the aria is a contemporary reflection on it. The concluding chorale often also appears as a chorale prelude in a central movement, and occasionally as a cantus firmus in the opening chorus as well. The best known of these cantatas are Cantata No. 4 ("Christ lag in Todesbanden"), Cantata No. 80 ("Ein feste Burg"), Cantata No. 140 ("Wachet auf") and Cantata No. 147 ("Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben").

In addition, Bach wrote a number of secular cantatas, usually for civic events such as weddings. The Coffee cantata, concerning a girl whose father won't let her marry until she gives up her coffee addiction, is the best known of these.

Motets

As part of Bach's regular church work, he copied and performed motets by many other composers (indeed, he usually began each Sunday service with one). These motets were mostly double-choir motets of the Venetian school, or more contemporary imitations of the style.

Bach wrote several motets himself, and they are also mostly for double choir. Exactly how many motets is a matter of dispute; there are six undoubted motets by Bach, a couple others of doubtful authorship, and some works classified in the BWV as cantatas but considered by some scholars to be motets. It is not certain for what occasion Bach wrote these works, but it is thought that most were for funerals.

There are no instrumental parts for these motets (except Lobet den Herrn, which has a continuo part), but it was typical of performance practice of the time to double vocal works with instruments and accompany them with continuo, so this method is often followed for modern performances; other performers do them a cappella.

Large works

Bach's large choral-orchestral works include the famous St. Matthew Passion and St. John Passion, both written for Holy Week services at the Thomaskirche, the Christmas Oratorio (a set of six cantatas for use in the Liturgical season of Christmas), a Magnificat in two versions, one in D major for a substantial orchestra with trumpets and timpani, and one for a smaller orchestra in E-flat major, with extra movements interpolated among the movements of the Magnificat text.

Bach's other large work, the Mass in B minor, was assembled by Bach near the end of his life, mostly from pieces composed earlier (such as Cantata 191 and Cantata 12). It was never performed in Bach's lifetime, or even after his death until the 19th century.

All these works, unlike the motets, have substantial solo parts as well as choruses.

Performances

In Bach's time musical ensembles were generally not as large as, say, in Brahms's. Few of his works were composed for more than a dozen musicians. This leaves the question as to whether present-day performers should adhere to authentic performance, or choose larger, modern orchestrations to which many of his works have been adopted. Some of his more important chamber musics do not indicate preferred instruments, leaving even larger space for arrangements.

Highly influential interpreters of Bach include Glenn Gould (piano), Helmut Walcha (organ), Pablo Casals (cello), Nathan Milstein (violin), Karl Richter (chorus and orchestra), Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt (cantatas, authentic performance), Joshua Rifkin and Andrew Parrott (choral works, one per part).

Transcriptions

Bach's music has inspired many composers to create music based on his themes, or transcribe his works for other instruments. His complete works for harpsichord have been edited or transcribed by Busoni, and Liszt wrote both a praeludium and fugue on the BACH motif. Another familiar transcription is the Ave Maria by Charles Gounod, based on the first prelude of the Well-Tempered Clavier.

Legacy

In his later years and after his death, Bach's reputation as a composer declined: his work was regarded as old-fashioned compared to the emerging classical style. He was far from forgotten, however: he was remembered as a player and teacher (as well, of course, as composer), and as father of his children (most notably C. P. E. Bach). His best-appreciated compositions in this period were his keyboard works, in which field other composers continued to acknowledge his mastery. Mozart and Beethoven were among his most prominent admirers. On a visit to the Thomasschule in Leipzig, Mozart heard a performance of one of the motets (BWV 225) and exclaimed, "Now, here is something one can learn from!"; on being given the parts of the motets, "Mozart sat down, the parts all around him, held in both hands, on his knees, on the nearest chairs. Forgetting everything else, he did not stand up again until he had looked through all the music of Sebastian Bach". Beethoven was also a devotee, learning the Well-Tempered Clavier as a child and later calling Bach "Urvater der Harmonie" ("original father of harmony") and "nicht Bach, sondern Meer" ("not a stream but a sea", punning on the literal meaning of the composer's name). [5] (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#fn_1)

The revival in the composer's reputation among the wider public was prompted in part by Johann Nikolaus Forkel's 1802 biography, which was read by Beethoven among others. Goethe became acquainted with Bach's works relatively late in life, through a series of performances of keyboard and choral works at Bad Berka in 1814 and 1815; in a letter of 1827 he compared the experience of listening to Bach's music to "eternal harmony in dialogue with itself". [6] (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#fn_2). But it was Felix Mendelssohn who did the most to revive Bach's reputation with his 1829 Berlin performance of the St. Matthew Passion. Hegel, who attended the performance, later called Bach a "grand, truly Protestant, robust and, so to speak, erudite genius which we have only recently learned again to appreciate at its full value". [7] (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#fn_3). Mendelssohn's promotion of Bach, and the growth of the composer's stature, continued in subsequent years. The Bach Gesellschaft (or Bach Society) was founded in 1850 to promote the works, and over the next half century it published a comprehensive edition.

Thereafter Bach's reputation has remained consistently high. During the 20th century the process of recognising the musical as well as the pedagogic value of some of the works has continued, perhaps most notably in the promotion of the Cello Suites by Pablo Casals. Another development has been the growth of the authentic or period performance movement, which attempts to present the music as the composer intended it. Examples include the playing of keyboard works on the harpsichord rather than a modern grand piano, and the use of small choirs or single voices instead of the larger forces favoured by 19th and early 20th century performers.

Johann Sebastian Bach's contributions to music, or, to borrow a term popularised by his student Lorenz Christoph Mizler, "musical science" are frequently compared to the "original geniuses" of William Shakespeare in English literature and Isaac Newton in physics.

Further reading

- The New Bach Reader by Hans T. David (Editor), Arthur Mendel, Christoph Wolff Publisher: W.W. Norton & Company; New Ed edition (1999) ISBN 0393319563

- J. S. Bach (Vol 1) by Albert Schweitzer Publisher: Dover Publications (1966) ISBN 0486216314

- Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician by Christoph Wolff Publisher: W.W. Norton & Company (2001) ISBN 0393322564

- J. S. Bach As Organist: His Instruments, Music, and Performance Practices by George Stauffer, Ernest May Publisher By Indiana University Press (1999)ISBN 025321386X

- The Bach Reader (W. W. Norton, 1966), edited by Hans T. David and Arthur Mendel, contains much interesting material, such as a large selection of contemporary documents, some by Bach himself.

- The early biography by Johann Nikolaus Forkel, Über Johann Sebastian Bachs Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke (1802), a translation of which is included in The Bach Reader (see above), is of considerable value, as Forkel was able to correspond directly with people who had known Bach.

- An early groundbreaking study of Bach's life and music is the multi-volume Johann Sebastian Bach (1889), by Philippe Spitta.

- Another famous study of his life and music is J. S. Bach (1908), by the versatile scholar and organist Albert Schweitzer.

- Christoph Wolff's more recent works (Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician and Johann Sebastian Bach: Essays) include a discussion of Bach's "original genius" in German aesthetics and music. Wolff gives an exciting account of the discovery of the famous Bach Family archive, evacuated from wartime Berlin's Singakademie to Silesia and from there vanished into Russia until just a few years ago, at <http://athome.harvard.edu/dh/wolff.html>.

- Douglas Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid uses the music of Bach, the art of M.C. Escher and a wide range of other ideas to explore topics such as cognition, formal methods, logic and mathematics, particularly Gödel's incompleteness theorem.

See also

- Bach family

- Glenn Gould

- Helmut Walcha

- Helmuth Rilling

- List of compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach

- List of recordings of compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach

- Rosalyn Tureck

- Wanda Landowska

References

- David, Hans T. and Mendel, Arthur The Bach Reader, W W Norton & Co Inc; Revised edition (May 1, 1966) ISBN 0393002594

- Forkel, Johann Nicolaus On Johann Sebastian Bach's Life, Genius, and Works, (1802), translated by A. C. F. Kollmann (1820)