Irish Houses of Parliament

|

|

The Irish Houses of Parliament (also known as the Irish Parliament House, now called the Bank of Ireland, College Green due to its modern day use as a branch of the bank) was the world's first purpose-built two-chamber parliament house. It served as the seat of both chambers (the Lords and Commons) of the Irish parliament of the Kingdom of Ireland for most of the eighteenth century until that parliament was abolished in the Irish Act of Union in 1800 when the island became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

In the 17th century, parliament had settled in Chichester House, a mansion in Hoggen Green (later renamed College Green) that had been owned by Sir George Carew, President of Munster and Lord High Treasurer of Ireland, and which had been built on the site of a nunnery disbanded by King Henry VIII after the dissolution of the monasteries. Carew's house, (later renamed Chichester House after a later owner Sir Arthur Chichester) was already a building of sufficient importance to have become a temporary home of the Kingdom of Ireland's law courts during the Michaelmas law term in 1605. Most famously, the legal documentation facilitating the Plantation of Ulster had been signed in the house on 16 November 1612.

| Contents |

Plans for the new building

The House was in a dilapidated state, allegedly haunted and unfit for parliamentary use. In 1727 parliament voted to spend £6,000 on the building of a new parliament building on the site. It was to be the first purpose-built two chamber parliament building in the world. The then ancient Palace of Westminster, the seat of the English (before 1707) and the Great British parliament, was merely a converted building; the House of Commons's odd seating arrangements was due to the chamber's previous existence as a chapel. Hence MPs faced each other from former pews, a seating arrangement continued when the new British Houses of Parliament were built in the mid nineteenth century after the mediæval building was destroyed by fire. (It was also followed in the 1940s, when the then House of Commons chamber was bombed during World War II, though consideration had been given to replacing it with a semi-circular chamber instead.)

The design of this radical new Irish parliamentary building, the one and only ever purpose-built Irish parliamentary building in history, was trusted to a talented young architect, Edward Lovett Pearce, who was himself a Member of Parliament and a protégé of the Speaker of the House of Commons, William Connolly of Castletown House. While building begun, parliament moved to the Blue Coat Hospital on Dublin's northside. The foundation stone for the new building was laid on the 3rd of February 1729.

Design of the new building

Missing image

Hoflentrance.jpg

The Irish House of Lords entrance to the Parliament House (east view)

The House of Lords entrance, which was part of an extension to the original building, was designed by renowned architect James Gandon

Pearce's design for the new Irish Houses of Parliament was revolutionary. The building was effectively semi-circular in shape, occupying nearly an acre and a half (6,000 m²) of ground. Unlike Chichester House, which was set far back from Hoggen Green, the new building was to open up directly onto the Green, as the above photograph shows. The principal entrance consisted of a colonnade of Ionic columns extending around three sides of the entrance quadrangle, forming a letter 'E' (see picture at the bottom of the page). Three statues, representing Hibernia (the Latin name for Ireland), Fidelity and Commerce stood above the portico. Over the main entrance, the royal coat of arms were cut in stone.

The building itself underwent extensions by renowned architect James Gandon (Pearce died young, robbing Ireland of a young architect of outstanding potential.) In particular, Gandon, who was responsible for three of Dublin's finest buildings, the Custom House, the Four Courts and the King's Inns, added on a new peers' entrance onto Westmoreland Street (shown above) at the east of the building between 1785 and 1789. Unlike the main entrance to the south, which came to be known as the House of Commons entrance, Gandon's peers' entrance used six Corinthian columns, at the request of peers who wished to have their entrance marked by a different look to the entrance of the commoners who used Ionic columns. Over the entrance, three statues were placed, representing Fortitude, Justice and Liberty. A curved wall joined the Pearce entrance to Gandon's extension. That this curved wall did not actually mark the exterior of the building but masked the actual uneven joins of some of the extension is shown in the view at the bottom of this page.

Missing image

Hoflchand1.jpg

The chandelier in the Irish House of Lords

The curved wall, though an instantly recognisable aspect of the building today, in fact bears little resemblance to the building as it was in its parliamentary days. Gandon's wall was built of granite, with inset alcoves. Another extension was made on the west side into Foster place by another architect, Robert Parke, in 1787; while matching Gandon's portico, he tried a different and highly unsuccessful solution, linking the other portico to the main Pearce one by a set of ionic pillars. The result proved unattractive. When the Bank of Ireland took over the building, it created an architectural unity by replacing this set of ionic columns by a curved wall similar to that built on the east side by Gandon. Ionic columns were then added to both curved walls, given the extensions an architectural and visual unity that had been lacking and producing the building's exterior as it is today.

The interior of the Houses of Parliament contained one unusual and highly symbolic act. While in many converted parliamentary buildings where both houses met in the one building, both houses were given equality or indeed the upper house was given a more symbolic location within the building, in the Irish Houses of Parliament the House of Commons was given pride of place with its octagonal parliamentary chamber located in the centre of the building. In contrast, the smaller House of Lords was demoted to a sideline position nearby. However the domed House of Commons chamber was later destroyed by fire. A less elaborate new chamber, minus its dome, was rebuilt in the same location and opened in 1796, four years before the House of Commons' ultimate abolition.

Pearce's design copied in the US Capitol and British Museum

Pearce's revolutionary designs came to be studied and copied both at home and abroad. The Viceregal Apartments in Dublin Castle copied his top-lit corridors, through with minor alterations that undermined the effect somewhat. The British Museum in London copied his colonnaded House of Commons entrance for its own facade. The impact of his designs stretched as far as Washington, DC where Pearce's building, and in particular his octagonal House of Commons chamber, was studied as plans were made for the new United States's new Capitol building. While the shape of the chamber was not replicated, some of its decorative motifs were, with the ceiling structure in the Old Senate Chamber and old House of Representatives chamber (now the Statuary Hall) holding a striking resemblance to the original Pearce-designed ceiling in the original House of Commons. Ironically, while the Capitol was copying aspects of the Irish parliament's design, the White House was being modelled on the ground and first floors1 of Leinster House, then the residence of one of the leading peers in the Irish House of Lords, the Duke of Leinster, and now the seat of the modern independent Irish parliament, Oireachtas Éireann.

A close-up of the House of Commons colonnade

The British Museum's facade is modelled on the colonnade (uncropped image)

The uniqueness of the building, the quality of its workmanship and its central location in College Green, across from Trinity College Dublin, made it one of Dublin's most highly regarded buildings, more highly regarded than its membership, some of whom were chosen from rotten boroughs and all of whom represented the Church of Ireland Anglo-Irish ascendancy in Ireland, not the vast majority of Irish people. In addition, it had little control of the Irish government, which was in fact a British government under a British Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Public ceremonial in the Irish Houses of Parliament

Much of the public ceremonial in the Irish Houses of Parliament mirrored that of the British House of Parliament. Sessions were formally opened by a Speech from the Throne by the Lord Lieutenant, whom it was written "used to sit, surrounded by more splendour than His Majesty on the throne of England"2. His Majesty's representative, when he sat on the throne, sat beneath a canopy of crimson velvet. The House of Lords was presided over, as in the English and British parliaments, by the Lord Chancellor, who sat on the woolsack, a large seat stuffed with wool from each of the three kingdoms, England, Ireland and Scotland. (Wool was seen as a symbol of economic success and wealth.) At the state opening, MPs were summoned from the nearby House of Commons chamber by Black Rod, a royal official who would "command the members on behalf of His Excellency to attend him in the chamber of peers". In the Commons, business was presided over by the Speaker, who in the absence of a government chosen from and answerable to the Commons was the dominant political parliamentary figure. Speaker Connolly remains today one of the most widely known figures ever to be produced by an Irish parliament, and not just for his role in parliament but also for his great wealth that allowed him to build one of Ireland's greatest Georgian houses, Castletown House.

Sessions of Parliament drew many of the wealthiest of Ireland's Anglo-Irish elite to Dublin, particularly as sessions often coincided with the Social Season, (January to 17 March) when the Lord Lieutenant presided in state over state balls and drawing rooms in the Viceregal Apartments in Dublin Castle. Leading peers in particular flocked to Dublin, where they lived in enormous and richly decorated mansions initially on the northside of Dublin, later in new Georgian residences around Merrion Square and Fitzwilliam Square. Their presence in Dublin, along with large numbers of servants, provided a regular boost to the city economy.

A ceiling in the 18th century

townhouse of a leading peer

Within a couple of years of the abolition of the Irish parliament, Viscount Powerscourt, who had been a member of the House of Lords, sold this Dublin residence. Many other peers also sold their palatial Dublin residences. Powercourt's residence is now a shopping centre.

The abolition of the parliament in 1800 had a major economic impact on the life of the city. Within a decade, many of the finest mansions (Leinster House, Powerscourt House, Aldborough House, etc) had been sold, often to government agencies. Though parliament itself was based on the exclusion of Irish Catholics, many catholic nationalist historians and writers blamed the absence of parliament for the increased impovertisation of Dublin, with many of the large mansions in areas like Henrietta Street sold to unscrupulous property developers and landlords who reduced them to tenements.

The draw of the viceregal court and its social season was not enough to encourage most Irish peers and their large entourage to come to Dublin anymore, their absence and that of their servants, with all their collective and previously excessive spending, severely hitting the economy of Dublin, which went into dramatic decline. By the 1830s and 1840s, nationalist leader Daniel O'Connell was leading a demand for the Repeal of the Act of Union and the re-establishment of an Irish parliament in Dublin, only this time one in which Catholics like O'Connell could now be elected to and sit in, in contrast with the entirely protestant assembly that had met in the old Houses of Parliament.

Abolition of Irish Parliament

In the last thirty years of the Irish parliament's existence, a series of crises and reforms changed the role of parliament. In 1782, following agitation by major parliamentary figures, but most notably Henry Grattan, the severe restrictions such as Poyning's Law that effectively controlled the Irish Parliament's ability to control its own legislative agenda were removed, producing what was known as the Constitution of 1782. A little over a decade later, Roman Catholics, who were by far the majority in the Kingdom of Ireland, were allowed to cast votes in elections to parliament, though they were still debarred from membership. The crisis over the 'madness' of King George III produced a major strain in Anglo-Irish relation, as both of the King's parliaments in both of his kingdoms possessed the theoretical right to nominate a regent, without the requirement that they choose the same person, though both in fact chose the Prince of Wales. The British government decided that the entire relationship between Britain and Ireland should be changed, with the merger of both states and parliaments. After one failed attempt, this finally was achieved, albeit with mass bribery of members of both Houses, who were awarded British and United Kingdom peerages and other 'encouragements'. In August 1800 parliament held its last session in the Irish Houses of Parliament. On 1st January 1801 the Kingdom of Ireland and its parliament ceased to exist, with the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland coming into being, with a united parliament meeting in Westminster, to which Ireland sent approximately 100 members3 while Irish peers had the constant right to elect a number of fellow Irish peers as representative peers to represent Ireland in the House of Lords, on the model already introduced for Scottish peers.

After 1800: From a parliament to a bank

The Irish House of Lords chamber

Formerly the bank boardroom, it is now used for recitals and book launches. The display in the picture is located on the dias where the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland's throne was placed.

William III's victory over James II/VII

The Battle of the Boyne tapestry that hangs in the Lords chamber.

Initially the former Houses of Parliament was used for a variety of purposes; as a militant garrison and an art gallery. In 1803 the fledgling Bank of Ireland bought the building from the British government for £40,000 for use as its headquarters. One provisio is stipulated; it must be so adapted that it never could be used as a parliament again. As a result, the only recently rebuilt House of Commons chamber, though one of Dublin's finest locations, was broken up to form a number of small offices but primarily replaced by a magnificent cash office added by the architect employed to oversee the conversion, Francis Johnston, then the most prominent architect working in Ireland. However contrary to the stipulation, the House of Lords chamber survived almost unscathed. It was used as the board room for the bank until in the 1970s the Bank of Ireland moved its headquarters to elsewhere. The chamber is now open to the public and is used for various publication functions, including music recitals.

Of the contents of the building, some have survived in different locations. The Mace of the House of Commons remained in the family of the last Speaker of the House of Commons, John Foster. The Bank of Ireland bought the Mace at a sale in Christies in London in 1937. The Chair of the Speaker of the House of Commons is now in the possession of the Royal Dublin Society, while a bench from the Commons is in the Royal Irish Academy. The original two tapestries have remained in the House of Lords. The Chandelier of the House of Commons now hangs in the Examination Hall of Trinity College Dublin. The woolsack, on which the Lord Chancellor of Ireland sat when chairing sessions of the House of Lords, is now back in location in the chamber on display. Copies of debates of the old Irish parliament are now kept in Ireland's modern day parliament house, Leinster House, so keeping a direct link between the old bicameral parliament of the Kingdom of Ireland and the modern day bicameral parliament of the modern Republic of Ireland.

The continuing symbolism of the Old Irish Houses of Parliament

From the 1830s under Daniel O'Connell, generations of leaders campaigned for the creation of a new Irish parliament, convinced that the Act of Union had been a great mistake. While O'Connell campaigned for full scale Repeal of the Act, leaders like Isaac Butt and Charles Stewart Parnell sought a more modest form of Home Rule within the United Kingdom, rather than the full recreation of an independent Irish state. However even if the proposal got through the British House of Commons (and the first two attempts, in 1886 and 1893 did not) the British House of Lords with its massive unionist majority was guaranteed to veto it. However the passage of the Parliament Act, 1911 which restricted the veto powers of the House of Lords, opened up the prospect that an Irish Home Rule Bill might indeed pass through both Houses, receive the Royal Assent and become law.

Missing image

Woolsack-crop.jpg

The woolsack on which the Lord Chancellor sat when chairing the House of Lords, now back in location in the Chamber.

Leaders from O'Connell to Parnell and later John Redmond spoke of the proud day when an Irish parliament might once again meet in what they called Grattan's Parliament in College Green. When, in 1911, King George V and his consort, Queen Mary visited Dublin where they attracted mass crowds, street sellers sold drawings of the King and Queen arriving in the not too distant future at the Old Houses of Parliament in College Green to open the new Irish parliament. In 1914, the Third Home Rule Act did indeed complete all parliamentary stages and receive the Royal Assent. The day when the old parliament would one day become the seat of parliament seemed around the corner. However the intervening First World War provided what proved to be a fatal delay for Home Rule. In 1916, a small band of radical republicans under Patrick Pearse staged the Easter Rising, in which they seized a number of prominent Irish buildings and proclaimed an Irish Republic. Surprisingly one building they did not take over was the old Parliament House. Perhaps they feared that as a bank it would be heavily protected. Perhaps, already expecting that the Rising would ultimately fail and that the reaction to the Rising and what Pearse called their "blood sacrifice", rather than the Rising itself, would reawaken Irish nationalism and produce independence, they did not seek to use the building for fear that it like the GPO would be destroyed in the British counter-attack. Or perhaps because of its association with a former ascendancy parliament, it carried little symbolism for their new 'republic'.

The Dáil choses a different home

Missing image

IrishHC1780.jpg

The Irish House of Commons by Francis Wheatley (1780).

This first Commons chamber was destroyed by fire. The rebuilt chamber was opened in 1796, only four years before parliament was abolished.

For whatever reason however the 'Bank of Ireland' as it was generally called, remained untouched. When in 1919, Irish republican MPs elected in the 1918 general election assembled to form the First Dáil and issue a Unilateral Declaration of Independence, they chose not to seek to use the old Irish parliament house but instead the Round Room of the Mansion House, the residence of the Lord Mayor of Dublin. (Ironically the Round Room had more royal connections than the Houses of Parliament; it had been built for the visit of King George IV in 1821) Though even if it had sought to use the old parliament house, it is exceptionally unlikely that the Bank of Ireland, then with a largely unionist board some of whom were descended from members of the former House of Commons and House of Lords, would have supplied the building for such a use, not least because it was also a working bank and the Bank's then headquarters . When in 1921, the House of Commons of Southern Ireland, created in the Fourth Home Rule Act (known as the Government of Ireland Act 1920) met (or supposedly met, only four MPs, all unionists, turned up for the state opening of parliament by the Lord Lieutenant), it assembled not in the old Parliament House but in the Royal College of Science.

In 1922, when the Provisional Government under W.T. Cosgrave made plans for the coming into being of the new Irish Free State, it gave little thought to using the old Houses of Parliament as the parliament building for the new state. Though larger than the building eventually selected, Leinster House, it possessed three major practical problems:

- It was the working headquarters of Ireland's major bank, which would need to have an alternative headquarters provided, were the state to use the building for parliamentary purposes;

- It lacked room around it for the provision of additional buildings to be used for governmental purposes. Directly behind it, on the actual location of Chichester House, there was now a major street called Fleet Street. In front of it on both the Lords and Commons entrances were major thoroughfares, College Green and Westmoreland Street, meaning that the only space for expansion was on its Foster Place side, yet here too there was little potential for the constitution of government offices. (In contrast the eventual choice, Leinster House, possessed the Royal College of Science, parts of which the state immediately 'borrowed' to use as a cabinet office, a prime ministerial office and offices for several ministries);

- While in the 18th century the fact that one of its House of Lords entrance opened directly onto a street caused little worry, in the Ireland of 1922 with a civil war raging it building was simply too insecure to be used as a modern day parliament building. While the House of Commons entrance was surrounded by railings, it offered only minimal parking space and minimal security from attack, and practically no means of escape in the event of an attack. In contrast Leinster House was located well in from the streets that surrounded it, had considerable parking potential and was far more secure in the event of an anti-treaty republican attack on the Free State Dáil and Seanad.

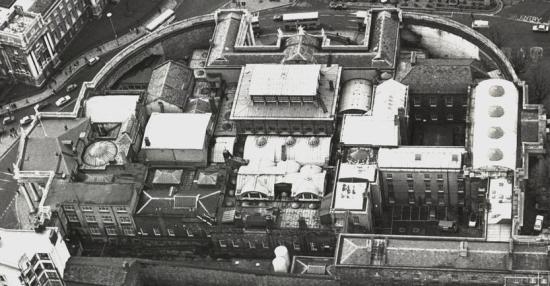

An aerial view of the building

This image is looking to the south colonnade (the 'E' shape) which is the original Pearse-designed entrance. Gandon's House of Lords eastern portico can be seen at the picture left. The House of Lords can be seen clearly as the white rectangular roof space with the small chimney on its bottom left-hand corner. (It actually stetches beyond that point, but that marks the main high ceiling. The dias for the throne and a matching area at the opposite end of the room do not reach as high). The original House of Commons location is indicated on this picture by a white roofspace on which three modern skylights can be seen, marking the centre of where the Commons chamber was. The large raised area of roof in the very heart of the building is that of the large public cash office designed by Francis Johnston as a replacement to the Commons chamber, almost evoking its memory positioned directly behind the main portico facing onto College Green. It is the dominant feature of the building's new use as a bank. The curved walls to each side of the building do not mark a real exterior wall but disguise the uneven structures behind as can be seen from this image.

As a result, the Free State initially hired Leinster House from its then owner, the Royal Dublin Society in 1922, before buying it in 1924. Longer term plans either to convert the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham into a national parliament, or to build a new parliament house, all fell through, leaving Leinster House as the accidential permanent modern Irish parliament house.

The 'screen wall' that joins the original entrance to Gandon's extension

The most recognisable image of the building, though ironically, while originally built by Gandon, it was given its modern appearance by the Bank of Ireland. A matching screen wall faces onto Foster Place on the other side of the building.

A curiously contradictory symbol

Ultimately the old Irish Houses of Parliament, the world's first purpose-built two-chamber parliament building, has remained a curiously contradictory symbol for Ireland: a parliament based on discrimination and exclusion that nevertheless, through producing radical leaders like Henry Grattan, is seen generally with affection by a people whose ancestors were debarred from membership. A parliament that, though protestant establishment in membership and loyal to the Crown, in 1782 produced the first real attempt at Irish independence, achieving the 'Constitution of 1782' that stressed its loyalty to the King by virtue of his Irish, not British Crown. Though flawed in its working, discriminatory in its membership and powerless in its ability to control the executive, it was used as a symbol by generations of nationalist leaders from O'Connell to Parnell and Redmond in their own quest for Irish self government. In a particular irony, Sinn Féin, which as a republican party fought for Irish independence during the Anglo-Irish War, was founded by a man, Arthur Griffith, who sought to restore the King, Lords and Commons of Ireland and the 1782 constitution to the centre of Irish governance, and the College Green Houses of Parliament to its position as the home of an Irish parliament.

Footnotes

1 The ground and first floors in British English are called the first and second floors in American English.

2 Unsourced eighteenth century quote used in the Bank of Ireland, College Green, an information leaflet produced by the Bank of Ireland about the Irish Houses of Parliament.

3 The number of Irish MPs in Westminster fluctuated slightly during Ireland's membership of the United Kingdom but generally remained in or around the 100 mark.

References

- 'History of the Irish Parliament 1692-1800' by E.M. Johnston-Liik (Ulster Historical Foundation, 2002)

- Volume 2 of 'The Unreformed House of Commons' by Edward and Annie G. Porritt (Cambridge University Press, 1903)