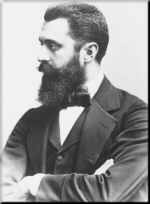

Theodor Herzl

|

|

Theodor Herzl (or Tivadar Herzl) (May 2, 1860 – July 3, 1904) was an Austrian Jewish journalist who became the founder of modern political Zionism. His Hebrew personal names were Binyamin Ze'ev.

Herzl was born in Budapest. He settled in Vienna in his boyhood, and was educated there for the law, taking the required Austrian legal degrees; but he devoted himself almost exclusively to journalism and literature. As a young man, he was engaged in the Burschenschaft association, which strove for German unity under the motto Ehre, Freiheit, Vaterland ("Honor, Liberty, Fatherland"). His early work was in no way related to Jewish life. He acted as correspondent of the Neue Freie Presse in Paris, occasionally making special trips to London and Istanbul. His work was of the feuilleton order, descriptive rather than political. Later he became literary editor of the Neue Freie Presse. Herzl at the same time became a writer for the Viennese stage, furnishing comedies and dramas.

| Contents |

Becomes leader of the Zionists

From April, 1896, when the English translation of his Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") appeared, his career and reputation changed. Herzl was moved by the Dreyfus affair, a notorious anti-Semitic incident in France; he had been covering the trial of Dreyfus for an Austro-Hungarian newspaper. He also witnessed mass rallies in Paris right after the Dreyfus trial where many chanted "Death To The Jews!"; this convinced him that it was futile to try to "combat" anti-Semitism. In June, 1895, in his diary, he wrote: "In Paris, as I have said, I achieved a freer attitude toward anti-Semitism, which I now began to understand historically and to pardon. Above all, I recognized the emptiness and futility of trying to “combat” anti-Semitism." Herzl grew to believe that anti-Semitism could not be defeated or cured, only avoided, and that the only way to avoid it was the establishment of a Jewish state.

His forerunners in the field of Zionism date through the nineteenth century, but of this perhaps he was least aware. Herzl followed his pen-effort by serious work. He was in Constantinople in April, 1896, and on his return was hailed at Sofia, Bulgaria, by a Jewish deputation. He went to London, where the Maccabeans received him coldly. Five days later he was given the mandate of leadership from the Zionists of the East End of London, and within six months this mandate was approved throughout Zionist Jewry. His life now became one unceasing round of effort. His supporters, at first but a small group, literally worked night and day. Jewish life had been heretofore contemplative and conducted by routine. Herzl inspired his friends with the idea that men whose aim is to reestablish a nation must throw aside all conventionalities and work at all hours and at any task.

In 1897, at considerable personal expense, he founded Die Welt of Vienna. Then he planned the first Zionist Congress in Basel. He was elected president, and held as by a magnet the delegates through all the meetings, being unanimously reelected at every following congress. In 1898 he began a series of diplomatic interviews. He was received by the German emperor on several occasions. At the head of a deputation, he was again granted an audience by the emperor in Jerusalem. He attended The Hague Peace Conference, and was received by many of the attending statesmen. In May, 1901, he was for the first time openly received by the Sultan of Turkey.

In 1902-03 Herzl was invited to give evidence before the British Royal Commission on Alien Immigration. As a consequence he came into close touch with members of the British government, particularly with Joseph Chamberlain, then secretary of state for the colonies, through whom he negotiated with the Egyptian government for a charter for the settlement of the Jews in Al 'Arish, in the Sinaitic peninsula, adjoining southern Palestine.

On the failure of that scheme, which took him to Cairo, he received, through L. J. Greenberg, an offer (Aug., 1903) on the part of the British government to facilitate a large Jewish settlement, with autonomous government and under British suzerainty, in British East Africa. At the same time, the Zionist movement being threatened by the Russian government, he visited St. Petersburg and was received by Sergei Witte, then finance minister, and Viacheslav Plehve, minister of the interior, the latter of whom placed on record the attitude of his government toward the Zionist movement. On that occasion Herzl submitted proposals for the amelioration of the Jewish position in Russia. He published the Russian statement, and brought the British offer before the sixth Zionist Congress (Aug., 1903), carrying the majority with him on the question of investigating this offer.

Judenstaat and Altneuland

Whereas his first brochure and his first congress address lacked all religious thought, and his famous remark that the return to Zion would be preceded by a return to Judaism seemed at the moment due rather to a sudden inspiration than to deep thought, subsequent events have proved that it was a true prophecy. His latest literary work, Altneuland, is devoted to Zionism. The author occupied the leisure of three years in writing what he believed might be accomplished by 1923. It is less a novel, though the form is that of romance, than a serious forecasting of what can be done when one generation shall have passed. The key-notes of the story are the love for Zion, the insistence upon the fact that the changes in life suggested are not utopian, but are to be brought about simply by grouping all the best efforts and ideals of every race and nation; and each such effort is quoted and referred to in such a manner as to show that Altneuland ("Old-Newland"), though blossoming through the skill of the Jew, will in reality be the product of the benevolent efforts of all the members of the human family.

Herzl envisioned a Jewish state that was devoid of most aspects of Jewish culture. He did not envision the Jewish inhabitants of the state being religious, or even speaking Hebrew. Proponents of a Jewish cultural rebirth, such as Ahad Ha'am were critical of Altneuland.

Herzl did not foresee any conflict between Jews and Arabs. The one Arab character in Altneuland, Reshid Bey, is very grateful to his Jewish neighbors for improving the economic condition of Palestine and sees no cause for conflict.

The name of Tel Aviv is the title given to the Hebrew translation of Altneuland by the translator, Nahum Sokolov. This name, which comes from Ezekiel 3:15, means tell - an ancient mound formed when a town is built on its own debris for thousands of years - of (the season) spring. The name was later applied to the new town built outside of Jaffa, which went on to become the second-largest city in Israel,

See also

External links

- English translation of Judenstaat (http://www.thelikud.org/Archives/Jewish%20State%20by%20Herzl.htm)

- "Altneuland" (http://www.wzo.org.il/en/resources/view.asp?id=1600)

- Herzl's Writing (http://www.wzo.org.il/en/resources/expand_author.asp?lastname=Herzl&firstname=Theodor)

- Zionism and the creation of modern Israel (http://www.zionismontheweb.org/zionism_history.htm)bg:Теодор Херцел

de:Theodor Herzl es:Theodor Herzl fr:Theodor Herzl id:Theodor Herzl he:בנימין זאב הרצל nl:Theodor Herzl ja:テーオドール・ヘルツル pl:Theodor Herzl pt:Theodor Herzl sk:Theodor Herzl sv:Theodor Herzl