Governor-General of Australia

|

|

Flag_of_the_Governor_General_of_Australia.gif

The Governor-General of Australia is a position established by the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act to sign legislation into law, appoint judges and ministers and perform many other important duties. In terms of protocol, the position is higher than any other Australian office. The Governor-General is President of the Executive Council and Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces.

According to the literal text of the constitution a "Governor-General appointed by the Queen shall be Her Majesty's representative in the Commonwealth . . ." The literal text also allows the Governor-General to exercise control over the federal government and veto legislation. These extensive powers are regulated by a convention (unwritten rule) where the Governor-General takes advice from the Prime Minister of Australia and other government ministers. In almost every situation, the advice must be followed, so in practice, the Governor-General rarely makes important decisions and never decides to veto legislation.

The day-to-day role of the Governor-General is to "encourage, articulate and represent those things that unite Australians as a nation". In this capacity, the Governor-General travels widely throughout Australia to open conferences, attend services and commemorations and generally "provide encouragement to individuals and groups who are contributing to their communities." [1] (http://www.gg.gov.au/textonly/role.html)

| Contents |

Relationship with the Queen

Sections 61 and 68 of the constitution state that the Governor-General exercises certain powers as the "Queen's representative" - originally referring to Queen Victoria, but now referring to Queen Elizabeth II, who resides in the United Kingdom. The limited form of this representation was explained in a 1988 Constitutional Commission report, that concluded "the Governor-General is in no sense a delegate of the Queen. The independence of the office is highlighted by changes which have been made in recent years to the Royal instruments relating to it".[2] (http://www.samuelgriffith.org.au/papers/html/volume8/v8chap8.htm)

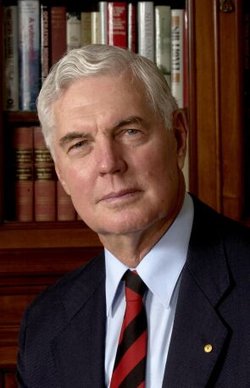

Although the Governor-General and the Queen occasionally observe certain formalities, in practice the Governor-General carries out his constitutional responsibilities without reference to the Queen. In 1975, the Queen, through her Private Secretary, wrote that she "has no part in the decisions which the Governor-General must take in accordance with the Constitution." [3] (http://www.aph.gov.au/house/pubs/PRACTICE/4Ch01.pdf) During the Australian constitutional crisis of 1975, the Queen refused to intervene on the basis that it would constitute an interference with Australian sovreignty. In 2004, Governor General Michael Jeffery said "her Majesty is Australia's head of state but I am her representative and to all intents and purposes I carry out the full role." [4] (http://www.theage.com.au/news/Gerard-Henderson/Queen-Camilla-of-Australia/2005/02/14/1108229927463.html) Other Governors-General have seen themselves as head of state, for instance Bill Hayden in his autobiography, where he mused that "The predominant objective of the republican movement is to eliminate reference to the Crown in the Constitution and with that to change the title of head of State from Governor General to President."

Official Residence

The main official residence of the Governor-General is Government House, Canberra, commonly known as Yarralumla. There is a second official residence, Admiralty House in Sydney. When the Governor-General visits the other states, he is usually a guest at the Government Houses in the state capitals.

History

The office of Governor-General was created when the Australian Constitution entered into force on January 1, 1901. The Governor-General was originally intended to be the personal representative of the monarch and the British Government, and was envisaged as one of the great offices of the British Empire, on par with the Viceroy of India. But the office never attracted candidates of the seniority originally envisaged, and Australian public opinion never accepted the idea of the Governor-General as an imperial pro-consul. Governors-General who were seen as "too grand" soon became unpopular.

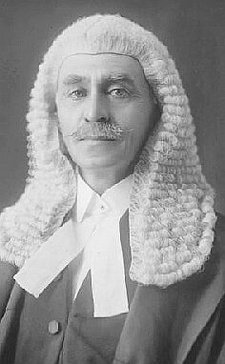

The first Governor-General, the Earl of Hopetoun, was British, as were all his successors until 1931. An Australian did not become Governor-General until the appointment of Sir Isaac Isaacs. The appointment of a non-Briton was denounced by the major conservative party of the time, the Nationalist Party of Australia as being "practically republican". Between 1931 and 1965 the issue of Australians as Governor-General was a party political one: although the Curtin government appointed the Duke of Gloucester in 1945, Labor governments generally appointed Australians, and conservative governments appointed British Governors-General.

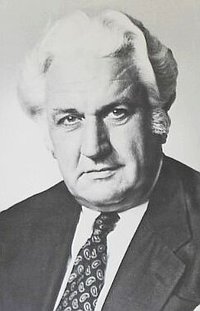

Since 1965, when the Menzies government appointed Lord Casey, the office has been held only by Australians, and it is unlikely that a non-Australian would ever again be nominated by an Australian Prime Minister. Suggestions that the Prince of Wales become the Governor-General have come to nothing, and this possibility seems increasingly remote. Since 1965 nine Australians have been appointed. Of these, three have been former politicians (Casey, Hasluck and Hayden); three have been judges (Kerr, Stephen and Deane); one has been an academic (Cowen); one a clergyman (Hollingworth); and one a professional soldier (Jeffery). In contrast to the Governors-General of Canada and New Zealand, there has not so far been been a female Governor-General, nor an Aboriginal, nor a citizen of any ethnic minority (unless one counts the two Jewish Governors-General, Isaacs and Cowen).

Most of the British Governors-General were peers: of the two who were not, Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson was a knight and Field Marshal Sir William Slim, was both a knight and a serving Field-Marshal. Of the Australian occupants, Casey was a peer and all the others were knights until the appointment of Hayden in 1988. All Governors-General down to Stephen were members of the Privy Council and thus had the additional title "Right Honourable." Australian appointments to the Privy Council ceased in practice in 1983 and in law in 1986.

Bill Hayden is thus the only Governor-General to have had no title at all. (Hayden even initially refused any honour in the Order of Australia, but was ultimately prevailed upon to accept a Companionship of the order (AC), as the Governor-General is the Chancellor of the order.) Shortly before assuming office as Governor-General, Hollingworth was awarded a Lambeth doctorate by the Archbishop of Canterbury; there was some discussion in the press about whether this was a substantive degree or merely honorary, and whether the reason for its granting was to provide Hollingworth with a title and to downplay his episcopal status.

Selection, appointment and role

Today the Governor-General is appointed by the monarch on the sole recommendation of the Prime Minister of Australia. Until 1930, however, the Governor-General was appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British Colonial Secretary, and the Australian government was merely asked, as a matter of courtesy, whether they approved of the choice or not. In 1930 Prime Minister James Scullin established the right of the Australian Prime Minister to advise the monarch directly, and also the right to appoint an Australian as Governor-General, although this did not become the established practice until 1965.

Until the 1920s the Governor-General represented both the monarch and the British Government, and was expected to exercise a supervisory role over the Australian Government in the manner of a colonial Governor. The Governor-General had the right to "reserve" legislation passed by the Parliament of Australia: in other words, to ask the Colonial Office in London for an opinion before giving the Royal Assent. This power was used several times.

As a result of decisions made at the Imperial Conference of 1926, the Governor-General ceased to be the diplomatic representative of the British Government (this role being taken over by a High Commissioner), and the British right of supervision over Australian affairs was abolished. Since the 1950s, however, and particularly since the office has come to be filled solely by Australians, the role of the Governor-General has again expanded. The Governor-General has come to be seen as, and to behave as, a Head of State. Governors-General, for example, now represent Australia abroad, and are accorded head of state honours, something that would have been unthinkable at the time the office was created.

On the resignation, death or incapacity of the Governor-General, or his absence from Australian territory, an Administrator assumes his powers: this is by convention the longest-serving state governor, who holds a dormant commission for this purpose. Only one Governor-General has died in office: Lord Dunrossil in 1961.

In May 2003 a new situation arose when Hollingworth stood aside temporarily while allegations against him were resolved, and the letters patent of the office were amended to take account of this. The senior state governor, Sir Guy Green of Tasmania, assumed office of Administrator when Hollingworth stood aside, and continued in this office when Hollingworth formally resigned.

One unresolved issue is the forced removal of a Governor-General before their term is complete - an event that has not yet occurred. It is generally accepted that the monarch would agree to dismiss the Governor-General on the written advice of the Australian Prime Minister, and replace them with the Prime Minister's nominee. However, it is unclear how quickly the monarch would act on such advice in a constitutional crisis, where a race could theoretically emerge between a Governor-General and the Prime Minister to dismiss the other. This was possibly one of the reasons why Kerr did not warn Whitlam of his intention to dismiss him in 1975.

Constitutional powers, functions and duties

The office of Governor-General is provided for by Sections 2 to 5 of the Constitution. These state:

- 2. A Governor-General appointed by the Queen shall be Her Majesty's representative in the Commonwealth, and shall have and may exercise in the Commonwealth during the Queen's pleasure, but subject to this Constitution, such powers and functions of the Queen as Her Majesty may be pleased to assign to him.

- 3. There shall be payable to the Queen out of the Consolidated Revenue fund of the Commonwealth, for the salary of the Governor-General, an annual sum which, until the Parliament otherwise provides, shall be ten thousand pounds. The salary of the Governor-General shall not be altered during his continuance in office.

- 4. The provisions of this Constitution relating to the Governor-General extend and apply to the Governor-General for the time being, or such person as the Queen may appoint to administer the Government of the Commonwealth; but no such person shall be entitled to receive any salary from the Commonwealth in respect of any other office during his administration of the Government of the Commonwealth.

- 5. The Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, and may also from time to time, by Proclamation or otherwise, prorogue the Parliament, and may in like manner dissolve the House of Representatives.

Further sections of the Constitution provide that:

- 58. When a proposed law passed by both Houses of the Parliament is presented to the Governor-General for the Queen's assent, he shall declare, according to his discretion, but subject to this Constitution, that he assents in the Queen's name, or that he withholds assent, or that he reserves the law for the Queen's pleasure. The Governor-General may return to the house in which it originated any proposed law so presented to him, and may transmit therewith any amendments which he may recommend, and the Houses may deal with the recommendation.

- 61. The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the Queen and is exercisable by the Governor-General as the Queen's representative, and extends to the execution and maintenance of this Constitution, and of the laws of the Commonwealth.

- 64. The Governor-General may appoint officers to administer such departments of State of the Commonwealth as the Governor-General in Council may establish. Such officers shall hold office during the pleasure of the Governor-General. They shall be members of the Federal Executive Council, and shall be the Queen's Ministers of State for the Commonwealth.

- 68. The command in chief of the naval and military forces of the Commonwealth is vested in the Governor-General as the Queen's representative.

In an administrative sense, the office of Governor-General is regulated by the Governor-General Act 1974 (http://scaleplus.law.gov.au/html/pasteact/0/284/top.htm).

The Governor-General, following the usages of the Westminster System, grants (or, in theory, may decline to grant) the Royal Assent to all Acts of the Australian Parliament, and many (though not all) Regulations made under those Acts. The Governor-General issues writs for the calling of elections, appoints (and may dismiss) Ministers of State including the Prime Minister, and chairs meetings of the Executive Council, a body which gives legal effect to the decisions of the Cabinet. In practice, however, most of these functions are carried out on the advice of the Prime Minister or other Cabinet ministers.

As well as the formal constitutional role, the Governor-General has a ceremonial role, though the extent and nature of this role has depended on the expectations of the time, the individual in office at the time and their reputation in the wider community. Governors-General generally become patrons of various charitable institutions, present honours and awards, host functions for various groups of people including ambassadors to and from other countries, and travel widely throughout Australia - replicating the actions of the monarch in the United Kingdom, or those of a ceremonial president such as the Republic of Ireland's. Sir William Deane described one of his functions as being "Chief Mourner" at prominent funerals.

This role can become controversial, however, if the Governor-General becomes unpopular with sections of the community. The public role adopted by Sir John Kerr was curtailed somewhat after the constitutional crisis of 1975, Deane's public statements on political issues produced some hostility towards him among conservatives, and some charities disassociated themselves from Dr Hollingworth after the issue of his management of sex abuse cases during his time as Archbishop of Brisbane became a matter of controversy.

The issue of becoming a republic (removing the constitutional ties with the British monarchy) continues to be raised in Australia, although the idea was defeated in a nationwide referendum held in 1999. In most of the proposed republican models, the office, powers and functions of the Governor-General are effectively preserved (in the practical sense described above), in a replacement President of Australia.

The reserve powers

Most of the official work of the Governor-General is carried out through the Federal Executive Council. Reserve powers are those which can be exercised directly.

In British practice, the reserve powers of the monarch are not explicitly stated in constitutional enactments and are the province of convention, but in Australia, the powers are explicitly given to the Governor-General in the Constitution and it is their use that is the subject of convention.

The reserve powers are:

- The power to dissolve (or refuse to dissolve) the House of Representatives. (Section 5 of the Constitution)

- The power to dissolve Parliament on the occasion of a deadlock. (Section 57)

- The power to withhold assent to Bills. (Section 58)

- The power to appoint (or dismiss) Ministers. (Section 64)

These powers are generally and routinely exercised on Ministerial advice, but the Governor-General retains the ability to act independently in certain circumstances, as governed by convention. It is generally held that the Governor-General may use his powers without ministerial advice in the following situations:

- if an election results in a hung Parliament, he may select the Prime Minister.

- if a Prime Minister loses the support of the House of Representatives through a 'No Confidence' motion, the Governor-General may appoint a new Prime Minister.

- if a Prime Minister advises a dissolution of the House of Representatives, the Governor-General may refuse that request. This is the most frequently used example of the use of the Governor-General's powers contrary to ministerial advice. It is worth noting that convention does not give the Governor-General the ability to dissolve either the House of Representatives or the Senate without advice.

Use of reserve powers is argued to be appropriate:

- if a Prime Minister advises a dissolution of Parliament on the occasion of a deadlock between the Houses, the Governor-General may refuse that request.

- if the Governor-General is not satisfied with a legislative Bill presented to him, he may refuse assent.

- if a Prime Minister resigns after losing a vote of confidence, the Governor-General may select a new replacement contrary to the advice of the outgoing Prime Minister.

- if a Prime Minister is unable to obtain supply and refuses to resign or advise a dissolution, the Governor-General may dismiss him or her and appoint a new Prime Minister.

The above is not an exhaustive list, and new situations may arise. The most famous and controversial use of the reserve powers occurred in November 1975. On this occasion Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed the government of Gough Whitlam when the Senate withheld supply to the government, despite the fact that Whitlam retained the confidence of the House of Representatives. Kerr determined that he had both the right and the duty to intervene, dismiss the government, and commission a new government that would recommend a dissolution of the Parliament. Despite the apparent endorsement of his action by the electorate at the 1975 elections the events surrounding the dismissal remain extremely controversial.

Governors-General of Australia

See also: Kings and Queens of Australia

Related articles

- Category:Governors-General of Australia

- History of Australia

- Constitutional history of Australia

- Governors of the Australian states

- British Empire

- Governor-General (links to other countries which have Governors-General)

Further reading

- Christopher Cunneen, Kings' Men: Australia's Governors-General from Hopetoun to Isaacs, Allen and Unwin, 1983

- Bill Hayden, Hayden: An Autobiography, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1996 (pp515, 519, 548)

External links

- The Office of the Governor-General (http://www.gg.gov.au)

- The use of the reserve powers (http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/rn/1997-98/98rn25.htm)