Giffen good

|

|

For most products, price elasticity of demand is negative. In other words, price and demand pull in opposite directions; price goes up and quantity demanded goes down, or vice versa. Giffen goods are an exception to this. Their price elasticity of demand is positive. When price goes up the quantity demanded also goes up, and vice versa. In order to be a true Giffen good, price must be the only thing that changes to get a change in demand.

Giffen goods are named after Sir Robert Giffen, who was attributed as the author of this idea by Alfred Marshall in his book Principles of Economics.

The classic example given by Marshall is of inferior quality staple foods whose demand is driven by poverty, which makes their purchasers unable to afford superior foodstuffs. As the price of the cheap staple rises, they can no longer afford to supplement their diet with better foods, and must consume more of the staple food.

Marshall wrote in the 1895 edition of Principles of Economics:

- As Mr. Giffen has pointed out, a rise in the price of bread makes so large a drain on the resources of the poorer labouring families and raises so much the marginal utility of money to them, that they are forced to curtail their consumption of meat and the more expensive farinaceous foods: and, bread being still the cheapest food which they can get and will take, they consume more, and not less of it.

| Contents |

Analysis of Giffen Goods

There are three necessary preconditions for this situation to arise:

- the good in question must be an inferior good,

- there must be a lack of close substitute goods, and

- the good must comprise a substantial percentage of the buyer's income.

If precondition #1 is changed to "The good in question must be so inferior that the income effect is greater than the substitution effect" then this list defines necessary and sufficient conditions.

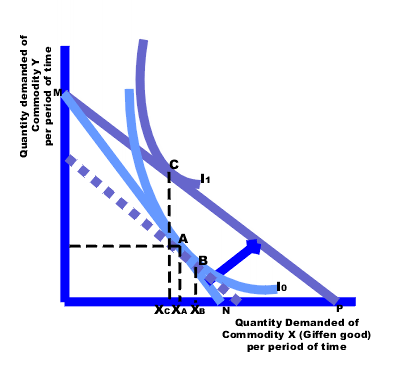

This can be illustrated with a diagram. Initially the consumer has the choice between spending their income on either commodity Y or commodity X as defined by line segment MN (where M = total available income divided by the price of commodity Y, and N = total available income divided by the price of commodity X). The line MN is known as the consumer's budget constraint. Given the consumer's preferences, as expressed in the indifference curve Io, the optimum mix of purchases for this individual is point A.

If there is a drop in the price of commodity X, there will be two effects. The reduced price will alter relative prices in favour of commodity X, known as the substitution effect. This is illustrated by a movement down the indifference curve from point A to point B (a pivot of the budget constraint about the original indifference curve). At the same time the price reduction causes the consumers’ purchasing power to increase, known as the income effect (a outward shift of the budget constraint). This is illustrated by the shifting out of the dotted line to MP (where P = income divided by the new price of commodity X). The substitution effect (point A to point B) raises the quantity demanded of commodity X from Xa to Xb while the income effect lowers the quantity demanded from Xb to Xc. The net effect is a reduction in quantity demanded from Xa to Xc making commodity X a Giffen good by definition. Any good where the income effect more than compensates for the substitution effect is a Giffen good.

Empirical evidence for Giffen goods

Despite years of searching, no generally agreed upon example has been found. A 2002 preliminary working paper by Robert Jensen and Nolan Miller made the claim that rice and noodles are Giffen goods in parts of China. It is easier to find Giffen effects where the number of goods available is limited, as in an experimental economy: DeGrandpre et al (1993) provide such an experimental demonstration. In 1991, Battalio, Kagel, and Kogut proved that quinine water is a Giffen good for lab rats. Thus, at least one real-world example of Giffen goods exists. One reason for the difficulty in finding Giffen goods is Giffen originally envisioned a specific situation faced by individuals in a state of poverty. Modern consumer behaviour research methods often deal in aggregates that average out income levels and are too blunt an instrument to capture these specific situations. It is for this reason that many text books use the term Giffen Paradox rather than Giffen Good.

Some types of premium goods (such as expensive French wines, or celebrity endorsed perfumes) are sometimes claimed to be Giffen goods. It is claimed that lowering the price of these high status goods can decrease demand because they are no longer perceived as exclusive or high status products. However, the perceived nature of such high status goods changes significantly with a substantial price drop. This disqualifies them from being considered as Giffen goods, because the Giffen goods analysis assumes that only the consumer's income or the relative price level changes, not the nature of the good itself. If a price change modifies consumers' perception of the good, they should be analysed as Veblen goods. Some economists question the empirical validity of the distinction between Giffen and Veblen goods, arguing that whenever there is a substantial change in the price of a good its perceived nature also changes, since price is a large part of what constitutes a product. However the theoretical distinction between the two types of analysis remains clear; which one of them should be applied to any actual case is an empirical matter.

See also

References

- DeGrandpre, R. J., Bickel, W. K., Rizvi, S. A., & Hughes, J. R. (1993). Effects of income on drug choice in humans. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 59, 483-500.

External links

- Jensen, Robert and Nolan Miller. "Giffen Behavior: Theory and Evidence. (http://ksgnotes1.harvard.edu/research/wpaper.nsf/rwp/RWP02-014?OpenDocument)" KSG Faculty Research Working Papers Series RWP02-014, 2002.

- The Last Word on Giffen Goods? (http://econpapers.hhs.se/paper/wpawuwpge/9602001.htm)de:Giffen-Paradoxon