Gerrymandering

|

|

Gerrymander_diagram_for_four_sample_districts.gif

Gerrymandering is a controversial form of redistricting in which electoral district or constituency boundaries are manipulated for electoral advantage, usually of incumbents or a specific political party, mainly in two-party first past the post systems. Gerrymandering may also be used to advantage or disadvantage a particular racial, linguistic, religious or class group. The word gerrymander serves both as a verb meaning to perpetrate the abuse and as a noun describing the resulting electoral geography.

| Contents |

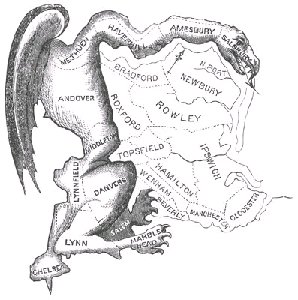

Origins of the term

The term is named after early Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry. In 1812, the Massachusetts legislature redrew legislative district lines to favor the Jeffersonian Republican party candidates. Two reporters were looking at the new election map and one commented that one of the new districts looked just like a salamander. The other retorted that it looked like a Gerry-mander. The name stuck and is now used by political scientists everywhere.

While Elbridge Gerry pronounced his name with a hard G as in "gate", the word "gerrymander" is usually pronounced with a soft G, as in "gem".

Overview

Gerrymandering is most effective in electoral systems with districts that elect a single representative, particularly plurality based systems such as first-past-the-post. Gerrymandering is possible, however, in any electoral system with multiple electoral districts. Among western democracies, only Israel and the Netherlands have electoral systems with only one (nationwide) electoral district.

One form of gerrymandering occurs when the boundaries of a constituency are changed in order to eliminate some area with a high concentration of people who vote in a similar way (e.g., for a certain political party). Another form occurs when an area with a high concentration of similar voters is split among several districts, ensuring that the party has a small majority in several districts rather than a large majority in one—this is commonly called "cracking". A converse method is to draw boundaries so that a group opposing those manipulating the boundaries are concentrated in as few areas as possible, so as to minimise their representation and influence—this is called "packing". Often, such gerrymandering is held to redress a long-overlooked imbalance, as when creating a black majority district.

Many electoral reform packages advocate fixed or neutrally defined district borders to eliminate this manipulation. One such scheme of neutrally defined district borders is bioregional democracy which follows the borders of terrestrial ecoregions as defined by ecology. Presumably, scientific criteria would be immune to politically motivated manipulation, although of course this is debatable as scientists are people with political interests too.

The problem with geographically static districting systems (which is not what most reform packages suggest) is that they do not take in to account changes in population, meaning that individual electors can grow to have vastly different degrees of influence on the legislative process. This is particularly a problem during times of large population movements, and was especially prominent in the United Kingdom during the industrial revolution. See also Reform Act and rotten borough.

For this reason, scientists have proposed algorithmic ways of dividing constituencies. Desirable criteria for the outcomes are:

- the system should be simple enough to be understood by most of the general population;

- the constituencies must be connected (i.e., each in a single piece);

- the constituencies should not be too elongated;

- the constituencies should have the same population or at least almost the same.

Gerrymandering is also possible in multi-member electoral systems, but generally the drawing of boundaries are only effective at determining which party wins the last seat in a close contest.

The Dame Shirley Porter case

Yet another method is to attempt to move the population within the existing boundaries. This occurred in Westminster, in the United Kingdom. The local government was controlled by the Conservative party, and the leader of the council, Dame Shirley Porter, conspired with others to implement the policy of council house sales in such a way as to shore up the Conservative vote in marginal wards by selling the houses there to people thought likely to vote Conservative. An inquiry by the district auditor found that these actions had resulted in financial loss to taxpayers, and Porter and three others were surcharged to cover the loss. Porter was accused of "disgraceful and improper gerrymandering" by district auditor John Magill. Those surcharged resisted this ruling with a legal challenge, but, in December 2001, the appeal court upheld the district auditor's ruling. Despite further lengthy legal argument Porter eventually accepted a deal to end the long-running saga, and paid £12 million (out of an original claimed £27 million plus costs and interest) to Westminster Council in July, 2004.

Gerrymandering in Northern Ireland

A particularly famous case occurred in Northern Ireland, where the Ulster Unionist Party government created electoral boundaries for the local council in Derry which, coupled with restrictions on voting rights based on economic status, ensured the election of a unionist council in a city where nationalists were in the overwhelming majority. This policy, coupled with a policy that gave council houses to unionists at the expense of nationalists all over the Six Counties (in one famous case, giving a council house to a single Protestant woman, employed by the UUP, rather than a large Catholic family who were at the head of the list), produced the Civil Rights Movement. The refusal of the government to consider equal rights in local government, and an end to gerrymandered discrimination, led indirectly to The Troubles.

Unionist apologists dismiss the gerrymandering of the Northern Ireland Assembly to be popular myth, claiming that the electoral boundaries for the Parliament of Northern Ireland were not gerrymandered to any great extent, and the electoral system originally used for this body Single Transferable Vote (STV) made it difficult to gerrymander successfully. However, this system of proportional representation was abolished in the late 1920s in favour of first-past-the-post. The Parliament of Northern Ireland was abolished in 1973, and STV was restored for elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly. (See Tullymandering below.)

Gerrymandering in the United States

California_District_38_2004.png

In the United States, gerrymandering has been used to cut minority populations in half to keep all minorities in the numerical minority, in as many districts as possible. This led to a major civil rights conflict; gerrymandering for the purpose of reducing the political influence of a racial or ethnic minority group is illegal in the United States under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but redistricting for political gain is legal.

The carving of territories into US states was also subject to gerrymandering, where before the American Civil War states were admitted on a formula of "one free state for each slave state". This nearly prevented Maine from seceding from Massachusetts until the Missouri Compromise was agreed upon, and it was decided that Texas and California would both enter as single—but large—states. During the late 19th century, the territories of the Rocky Mountains were split up into relatively small states to help the Republican Party maintain control of the White House—each new state brought in three electoral votes (Compare a map of the United States in 1860 [1] (http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/united_states/us_terr_1860.jpg) with a map from 1870 [2] (http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/united_states/us_terr_1870.jpg)).

As for state-internal gerrymandering, there have been attempts to create "majority minority" districts, also called "affirmative gerrymandering" or "racial gerrymandering", to ensure higher ethnic minority representation in government. However, gerrymandering based solely on race has been ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court, under the Fourteenth Amendment first by Shaw v. Reno (1993) and by subsequent cases, including Miller v. Johnson (1995) and Hunt v. Cromartie (1999).

There is ambiguity as to how far racial considerations can be permitted. The 4th Congressional District of Illinois is a case in point. The stated goal of allowing the unusual "earmuff" shape was to redress previous discrimination.IL04_109.gif

The possibility of gerrymandering makes the process of redistricting extremely politically contentious within the United States. Under U.S. law, districts for members of the House of Representatives are redrawn every ten years following each census and it is common practice for state legislative boundaries to be redrawn at the same time. Battles over contentious redistricting take place within state legislatures, which are responsible for creating the electoral maps in most states, as well as federal courts. Sometimes this process creates strange bedfellows; in some states, Republicans have cut deals with African American Democratic state legislators to create majority black districts. These districts essentially ensure the election of an African American Congressman, but due to voting patterns, end up concentrating the Democratic vote in such a way that surrounding districts are more likely to vote Republican.

The introduction of computers has made redistricting a more precise science, but the incentives for certain groups to create maps that increase their delegation in Congress remain. Many political analysts have argued that the United States House of Representatives has been gerrymandered to the point that there are now very few contested seats, and have also argued that this has a number of detrimental effects, among which is that the lack of contested seats makes it unnecessary for candidates to attract middle voters and to compromise across party lines. This lack of necessity to compromise is demonstrated by the large number of party-line votes in the Congress, with very few or no Representatives or Senators voting out of alignment with fellow party members.

Gerrymandering in Germany

When the electoral districts in Germany where redrawn in 2000, the ruling Social-Democrat Party SPD used gerrymandering to marginalize the socialist PDS party in its strongholds in eastern Berlin. After winning four seats in Berlin in the 1998 national election, the PDS kept only two of them after the following 2002 elections. This caused the drop out of the PDS of the Bundestag (the German parliament): Due to German electoral law a political party has to win either more than five percent of the votes or at least three seats to move in.

Incumbent gerrymandering

Gerrymandering can also be done to help incumbents, effectively turning every district into a packed one and greatly reducing the potential for competitive elections. This is particularly likely to occur when the minority party has significant obstruction power - unable to enact a partisan gerrymander, the legislature instead agrees on ensuring their own mutual reelection.

For example, in an unusual occurrence, the two dominant parties in the state of California in 2000 cooperatively redrew both state and federal legislative districts to preserve the status quo, ensuring the safety of the politicians from possibly unpredictable voting by the electorate. For more information see California bi-partisan gerrymandering.

Tullymandering

In the Republic of Ireland, in the mid-1970s, the Minister for Local Government, James Tully, attempted to arrange constituencies to ensure that the governing National Coalition would win a parliamentary majority. This was planned as a major reversal of previous gerrymandering by the Fianna Fáil party (then in opposition). He ensured that there were as many as possible three-seat constituencies where the governing parties were strong, in the expectation that the governing parties would each win a seat in many constituencies, relegating the Fianna Fáil party to one out of three. In areas where the governing parties were weak four-seat constituencies were used so that the governing parties had a strong chance of winning two still. In fact the process backfired spectacularly due to a larger than expected collapse in the vote, with Fianna Fáil winning a landslide victory, two out of three seats in many cases, relegating the National Coalition parties to fight for the last seat. Consequently, the term tullymandering was used to describe the phenomenon of a failed attempt at gerrymandering.

See also

External links

- Gerrymandering in the US (http://www.fairvote.org/articles/bbcnews100804.htm)

- Anti-Gerrymandering policy in Australia (http://www.abc.net.au/elections/federal/2004/items/200408/s1172393.htm)

- A collection of bizarre and unconstitutional districts from recent history, dedicated to Governor Eldridge Gerry. (http://www.westmiller.com/fairvote2k/in_gerry.htm)

- Beyond gerrymandering and Texas posses: US electoral reform (http://www.worldpolicy.org/globalrights/democracy/2003-0529-CSM-gerrymandering.html)

af:Afbakeningsknoeiery da:Gerrymandering de:Gerrymandering eo:Gerrymander es:Gerrymandering fr:Gerrymandering ja:ゲリマンダー