Cladistics

|

|

Template:Spoken Wikipedia Cladistics (Greek: clados = branch) or phylogenetic systematics (Greek: phylon = race and genetikos = relative to birth, from genesis = birth) is a branch of biology that determines the evolutionary relationships of living things based on derived similarities. It forms the basis for most modern systems of classification, which seek to group organisms by evolutionary relationships. In contrast, phenetics groups organisms based on their overall similarity, while more traditional approaches tend to rely on key characters. Willi Hennig is widely regarded as the founder of cladistics.

| Contents |

Introduction

Based on a wide variety of information, which includes genetic analysis, biochemical analysis, and analysis of morphology, treelike relationship-diagrams called "cladograms" are drawn up to show different possibilities.

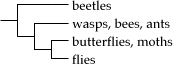

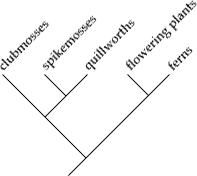

In a cladogram, all organisms lie at the leaves, and each inner node is ideally binary (two-way). The two taxa on either side of a split are called sister taxa or sister groups. Each subtree, whether it only contains one item or a hundred thousand, is called a clade. A correct cladogram should have all the organisms contained in any one clade share a unique ancestor for that clade, one which they do not share with any other organisms on the diagram. Each clade should be set off by a series of characteristics that appear in its members but not in the other forms it diverged from. These identifying characteristics of a clade are called synapomorphies (shared, derived characters). For instance, hardened front wings are a synapomorphy of beetles, while circinate vernation, or the unrolling of new fronds, is a synapomorphy of ferns.

Several more terms are defined for the description of cladograms and the positions of items within them. In an upright cladogram (one with species listed at the top, and a "root" at the bottom), a species or clade is basal to another clade if it branches off toward the bottom, or below the other group in question. Conversely, one clade or species can be described as nested within another. Thus in a cladogram that includes four mammals and a bird, the bird's branch is basal, but a dog would be nested within the mammals. Similarly, a character-state (see below) that seems to be possessed by the common ancestor of a group is described as ancestral, and one that evolved later is comparatively derived. The latter two terms are used instead of "primitive" and "advanced" to avoid placing value-judgements on the evolution of the character states.

Cladistic methods

Typically, an analysis begins by collecting information on certain features of all the organisms in question. Features may come in different versions (i.e. feather-color may be blue in one species, but red in another). These features are collectively called characters, and specific versions are called character states. Thus we might say that "red feathers" and "blue feathers" are two character states of the character "feather-color."

After recording many character states, the researcher then decides which ones were present before the last common ancestor of the group of species (symplesiomorphies) and which were present in the last common ancestor (synapomorphies). Usually this is done by considering some outgroup of organisms we know are not too closely related to any of the organisms in question. Only synapomorphies are of any use in characterising cladistic divisions.

Next, different possible cladograms are drawn up and evaluated. Clades are typically drawn so that they can have as many synapomorphies as possible. The hope is that a sufficiently large number of true synapomorphies should be large enough to overwhelm any unintended symplesiomorphies (homeoplasies), caused by convergent evolution (i.e. characters that resemble each other because of environmental conditions or function, and not because of common ancestry. A well-known example of convergent evolution is wings. Though the wings of birds and insects may superficially resemble one another and serve the same function, each evolved independently from the other). If a bird and an insect were both accidentally scored "POSITIVE" for the character "presence of wings", a homeoplasy would be introduced into the dataset, and it might cause erroneous results.

In practice, neutral features like exact ultrastructure (a term for extremely fine structure, microscopic or molecular composition of cellular structure) may be used to provide evidence for real relationships even when the appearance of organisms makes it otherwise difficult. When equivalent possibilities turn up, one is usually chosen based on the principle of parsimony: the most compact arrangement is likely the best (a variation of Occam's razor). Another approach, particularly useful in molecular evolution, is maximum likelihood, which selects the optimal cladogram that has the highest likelihood based on a specific probability model of changes.

Cladistics has taken a while to settle in, and there is still wide debate over how to apply Hennig's ideas in the real world. In particular, apomorphies are not always easy to distinguish and data are often unavailable due to a sparsity of available forms or a lack of knowledge of characters, and these may invalidate cladograms. There is also concern that use of widely different data sets, for instance structural versus genetic characteristics, may produce widely different trees. However, by and large the phylogenetic approach to systematics has proven useful and coherent and has gained general support.

As DNA sequencing has become easier, phylogenies are increasingly often constructed with the aid of molecular data. Computational systematics allows the use of these large data sets to construct objective phylogenies. These can more accurately filter out true synapomorphy from parallel evolution.

Cladistics does not assume any particular theory of evolution, only the background knowledge of descent with modification. Thus, cladistic methods can be, and recently have been, usefully applied to non-biological systems, including determining language families in historical linguistics and the filiation of manuscripts in textual criticism.

Cladistic classification

A recent trend in biology since the 1960s, called cladism or cladistic taxonomy, has been to require taxa to be clades. In other words cladists argue that the classification system should be reformed to eliminate all non-clades. In contrast, other evolutionary taxonomists insist that groups reflect phylogenies and often make use of cladistic techniques, but allow both monophyletic and paraphyletic groups as taxa.

A monophyletic group is a clade, comprising an ancestral form and all of its descendants, and so forming one (and only one) evolutionary group. A paraphyletic group is similar, but excludes some of the descendants that have undergone significant changes. For instance, the traditional class Reptilia excludes birds even though they evolved from the ancestral reptile. Similarly, the traditional Invertebrates are paraphyletic because Vertebrates are excluded, although the latter evolved from an Invertebrate.

A group with members from separate evolutionary lines is called polyphyletic. For instance, the once-recognized Pachydermata was found to be polyphyletic because elephants and rhinoceroses arose separately from non-pachyderms. Evolutionary taxonomists consider polyphyletic groups to be errors in classification, often occurring because convergence or other homoplasy was misinterpreted as homology.

Following Hennig, cladists argue that paraphyly are as harmful as polyphyly. The idea is that monophyletic groups can be defined objectively, in terms of common ancestors or the presence of synapomorphies. In contrast, paraphyletic and polyphyletic groups are both defined based on key characters, and the decision of which characters are of taxonomic import is inherently subjective. Many argue that they lead to "gradistic" thinking, where groups advance from "lowly" grades to "advanced" grades, which can in turn lead to the error of teleology.

Going further, some cladists argue that ranks for groups above species are too subjective to present any meaningful information, and so argue that they should be abandoned. Thus they have moved away from Linnaean taxonomy towards a simple hierarchy of clades.

Other evolutionary systematists argue that all taxa are inherently subjective, even when they reflect evolutionary relationships, since living things form an essentially continuous tree. Any dividing line is artificial, and creates both a monophyletic section above and a paraphyletic section below. Paraphyletic taxa are necessary for classifying earlier sections of the tree - for instance, the early vertebrates that would someday evolve into the family Hominidae can not be placed in any other monophyletic family. They also argue that paraphyletic taxa provide information about significant changes in organisms' morphology, ecology, or life history - in short, that both taxa and clades are valuable but distinct notions, with separate purposes. Many use the term monophyly in its older sense, where it includes paraphyly, and use the alternate term holophyly to describe clades (monophyly sensu Hennig).

A formal code of phylogenetic nomenclature, the PhyloCode, is currently under development for cladistic taxonomy. It is intended for use by both those who would like to abandon Linnaean taxonomy, and by those who would like to use taxa and clades side by side.

See also

- Scientific classification

- tree of life

- Phylogenetic tree

- Systematics

- Taxonomy

- Willi Hennig

- Important publications in cladistics

References

- Kitching IJ, Forey PL, Humphries CJ and Williams DM (1998) Cladistics, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Patterson C (1982) Morphological characters and homology. In: Joysey KA and Friday AE (eds) Problems in Phylogenetic Reconstruction. London: Academic Press.

- Swofford DL, Olsen GJ, Waddell PJ and Hillis DM (1996) Phylogenetic inference. In: Hillis DM, Moritz C and Mable BK (eds) Molecular Systematics. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- de Quieroz K and Gauthier JA (1992) Phylogenetic taxonomy. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 23: 449–480.

- Wiley EO (1981) Phylogenetics: The Theory and Practice of Phylogenetic Systematics. New York: Wiley Interscience.

External links

- The Willi Hennig Society (http://www.cladistics.org)

- Journey into Phylogenetic Systematics (http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/clad/clad4.html)

- Tree of Life Web Project (http://tolweb.org/tree/phylogeny.html)

- extensive bibliography (http://occamssword.com) for parsimony in Biology and the Philosophy of Biology

- Example of cladistics used in textual criticism (http://rjohara.net/darwin/files/bmcr.html)

- The Compleat Cladist (pdf) (http://www.amnh.org/learn/pd/fish_2/pdf/compleat_cladist.pdf)de:Kladistik