Celtic Tiger

|

|

"The Celtic Tiger" is a nickname for the Republic of Ireland during its period of rapid economic growth between the 1990s and 2001 or 2002. Strictly speaking, the term is used for both the period of time (as in Celtic Tiger years) and the country during that period.

The actual term Celtic Tiger was first used by Irish economist and broadcaster David McWilliams in 1994. The term is an analogy to the nickname "East Asian Tigers" applied to South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and other countries of East Asia during their period of rapid growth in the 1980s and 1990s. The Celtic Tiger or Celtic Tiger economy is often also called The Boom or Ireland's Economic Miracle. Sometimes the Celtic Tiger moniker is also used when referring to continued or renewed Irish economic prowess subsequent to the aforesaid time period.

| Contents [hide] |

|

|

The Celtic Tiger

The original Celtic Tiger occurred in the late 1990s and lasted until the worldwide economic downturn of 2001. Between 1991 and 2003 the Irish economy grew by an average of 6.8% annually [1] (http://caliban.sourceoecd.org/vl=2490615/cl=71/nw=1/rpsv/factbook/02-02-01-g01.htm), dramatically raising Irish living standards to equal and eventually surpass those of many states in the rest of Western Europe. The peak of this growth was in 1999 when GDP growth hit 11.1%, after being 8.7% and 10.8% in 1998 and 1997 respectively. Despite this high level of growth for so many years the economy continued to grow at above 6% in 2001, 2002 and 2003. [2] (http://caliban.sourceoecd.org/vl=2490615/cl=71/nw=1/rpsv/factbook/02-02-01-g01.htm)

Causes

(Key Sources: Dr. Dermot McAleese report on Causes (http://ipac.ca/toronto/news_highlights/fall2001/celtic.htm), Markets Created a Pot of Gold in Ireland by Benjamin Powell (http://www.cato.org/dailys/04-21-03.html), The Economist Magazine Report 14th Oct 2004 (http://www.economist.com/printedition/displayStory.cfm?Story_id=3261071))

Ireland_tax_comparison.jpg

The following are some of the main causes of the Celtic Tiger

Many economists give credit for Ireland's growth to a low corporate taxation rate (10 to 12.5 percent throughout the late 1990s) and subsidies called transfer payments from the more developed members of the EU like France and Germany that were as high as 7% of GNP [3] (http://www.policyalternatives.ca/manitoba/fastfactsmay25.html). This aid was used to increase investment in the education system (university tuition is free) and physical infrastructure. These investments increased the productive capacity of the Irish economy and made it more attractive to high tech employers. A more sceptical interpretation is that much of the growth was due to the fact that the economy of Ireland had lagged the rest of northwestern Europe for so long that it had become the one of few remaining sources of a relatively large, low-wage labour pool left in Western Europe. Ireland's membership of the European Union since 1973 has helped the country gain access to the huge markets of Europe, in addition to EU subsidies. Ireland's trade had previously been predominantly through the United Kingdom.

The provision of subsidies and investment capital by Irish organisations such as IDA Ireland, successfully attracted a large variety of high profile companies (such as Dell, Intel, Microsoft and Gateway) throughout the 1990s to locate in Ireland. These companies were attracted to Ireland because of its European Union membership, relatively low wages, government grants and low tax rates. In addition, Ireland had a young, well-educated, English-speaking labour force [4] (http://www.idaireland.com/home/index.aspx?id=33). These abilities gave Irish workers the ability to easily and efficiently communicate with Americans, a factor that was vital in the choice of Ireland for European headquarters, as opposed to other low-wage EU nations such as Portugal and Spain. Another major factor making Irish staff more attractive to multi national employers was the massive growth in worker productivity in Ireland between 1994 and 2003 - which amounted an average 4% increase annually [5] (http://caliban.sourceoecd.org/vl=2490615/cl=71/nw=1/rpsv/factbook/02-03-01-g01.htm)[6] (http://caliban.sourceoecd.org/vl=2490615/cl=71/nw=1/rpsv/factbook/02-03-02-g01.htm). As employee wages increased in the late 1990's, the overall cost of employing an Irish worker remained low due to a very low tax wedge of less than 5%. This compares with over 40% in Sweden and over 30% in Germany. (source: The Economist 21/3/05)

A favourable time zone difference [7] (http://www.geog.ubc.ca/iiccg/papers/Breathnach_P.html) allowed Irish employees to work at the same time U.S. workers slept. This was particularly attractive to companies with large legal and financial departments; an Irish lawyer could work on a lawsuit overnight while his American counterpart slept. Little government intervention in business compared to other EU members and particularly countries in Eastern Europe assured U.S. firms of a stable operating environment. Growing stability in Northern Ireland brought about by the Belfast Agreement further established Ireland's image as having a stable operating environment. The building of the International Financial Services Centre in Dublin led to the creation of 14,000 high-value jobs in the accounting, legal and financial management sectors.

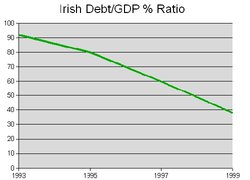

Charlie McCreevy the Minister for Finance between 1997 and 2004 pursued fiscal policies such as low taxation [8] (http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1255033/posts) and managed to reduce the public debt [9] (http://www.business2000.ie/cases/cases_7th/case21.htm) dramatically over the boom years. He was voted Ireland's best Minister for Finance of all time in 2004 by the Finance Magazine [10] (http://www.accountingnet.ie/content/publish/article_749.shtml). Charlie McCreevy left his post as Minister for Finance in 2004 to work in the European Commission.

Consequences

During the Celtic Tiger period, Ireland was transformed from one of the poorest countries in Western Europe to one of the wealthiest. After successive governments led by weak and often corrupt politicians such as the now disgraced Charles Haughey, the country was rapidly transformed to become one of Europe's richest nations. The major consequences of the Celtic Tiger included:

Economic consequences

- Disposable income soared to record levels enabling a huge rise in consumer spending. It became a common sight to see expensive cars and designer labels around the nation's towns and cities.

- Unemployment fell from 18% in the late 1980s to 4.2% in 2005 and average industrial wages grew at one of the highest rates in Europe.

- Inflation regularly brushed 5% per annum, pushing Irish prices up to match those of the Nordic Europe. Groceries were particularly hard hit, prices in chain stores in the Republic of Ireland were sometimes up to twice those in Northern Ireland

- Public debt was dramatically cut (it stood at about 34% of GDP by the end of 2001) to become one of Europe's lowest, enabling public spending to double without any significant increase in taxation levels.

- A large investment in modernising Irish infrastructure and city streetscapes resulted from the new wealth - the National Development Plan led to large investments in road infrastructure and new transport services came on stream such as the Luas and the Dublin Port Tunnel. Local authorities were able to take the initiative to build new monuments such as the Spire of Dublin and enhance street appearance with repaving, new benches, trees, bins etc.

Social and cultural consequences

- Ireland's historic trend of emigration was stopped and Ireland even started to become a destination for many immigrants - this significantly changed Irish demographics and resulted in expanding multiculturalism, particularly in the Dublin area.

- Growing wealth was blamed for rising crime levels among youths, particularly increased alcohol-related violence resulting from increased spending power.

- Many in Ireland believe that the Culture of Ireland was eroded in the Boom years by growing consumerism and the adoption of American capitalist ideals.

- The growing success of Ireland's economy raised the low confidence and lowered self-doubt that plagued Irish society for decades. For many years Ireland seemed to have a chip on its shoulder; however, Irish people are now far quicker to participate in activities and to take risks such as setting up businesses.

- Many young people left the rural countryside, to live and work in urban centres. This has increased the urbanisation of Ireland.

- The "Celtic Tiger" period was marked by - even preceded by - an enormous change in social attitudes in Ireland - divorce and homosexuality were legalised, pro-life referenda were defeated (twice) and two women (including one as the Irish Labour Party candidate) were elected president. The Republic of Ireland became recognisably a modern European state in terms of social policy.

- Arguably the boom also contributed to Ireland's new cultural and even sporting confidence and success - footballer Ray Houghton, Riverdance and U2 are typical symbols.

- Although not the sole reason, the Celtic Tiger certainly aided the Peace Process in Northern Ireland. An end to The Troubles is now a much closer reality than it was in the 1980s. Growing cross border trade brought the different communities together, and a lower unemployment rate on both sides of the border put an end to the old phrase the devil makes use of idle hands in the context of Northern Ireland.

Criticism of government management of the boom

Despite the economic success of Ireland during the Celtic Tiger period, the government came under heavy criticism for poor management and neglect of certain government responsibilities. These included:

- The Irish health service did not receive any significant fundamental reform during the period. Despite a doubling in the health budget, waiting lists, bed shortages and shortstaffing remained widespread - the system is often colloquially referred to as "The Eleven Kingdoms".

- Despite government promises, the transport sector was not reformed - the government airport monopoly, Aer Rianta, remained in existence until 2004, bus transport was still largely controlled by the monopoly Bus Eireann, and the railway monopoly Iarnrod Eireann remained highly inefficient and overly subsidised.

- The road network became congested and struggled to cope with the many new commuters, particularly in the East. However new motorways and road upgrades only started materialising in the 2000s - at a much higher cost than expected.

- The telecommunications industry, controlled by the former state monopoly Eircom, failed to upgrade the country's network infrastructure quickly enough - Broadband penetration remained near 1% until mid 2003 when the government finally started to incentivise a broadband roll-out.

- Despite promises to increase Garda (police) ranks by 3,000 members before the government's end of term in 2002, Garda numbers failed to increase as promised.

- To encourage a slowdown in consumer spending in the hopes of dampening inflation, the government launched the SSIA (Special Savings Incentive Account) scheme. The interest on SSIAs in banks is to a large extent funded by the state - most banks have only made a token gesture (if any at all). Irish banks, traditionally, give very low interest on savings accounts and this is reflected on these accounts; the state guaranteed a return of 25%. On a fundamental level the states contribution is subsidy on the banks with taxpayers paying their own interest. Also recently the extent of the monopoly and overcharging of Irish banks generally has come to light with several scandals and reports on the lack of competition in the sector.

The downturn 2001-2003

The Celtic Tiger came to a sudden halt in 2001 after a half decade of astonishingly high growth. The Irish economic downturn was in-line with the worldwide downturn - largely due to Ireland's close US economic ties. The major factors behind the sudden slowdown in the Irish economy included:

- A large drop in investment in the worldwide IT industry caused by the over-expansion of the industry in the late 1990s and the resulting stock market crash. Ireland at the time was a major player in the industry - being the worlds largest exporter of software (even ahead of the USA) and a home to the European operations of many US computer manufacturers.

- Foot and mouth disease and the September 11, 2001 attacks damaged Ireland's tourism sector (as well as the agricultural sector), deterring the heavy spending US and British tourists that the industry depended on.

- Several companies moved operations to Eastern Europe and China due to a rise in Irish wage-costs, insurance premiums and a general loss of Irish competitiveness.

- The rising value of the Euro hit non-EMU exports - particularly those to the USA and Britain.

However the downturn was not a full blown Recession, merely a slowdown in the rate of Irish economic expansion. Signs of a recovery became evident in late 2003 as US investment levels increased once again.

Worldwide situation

At the same time, the rest of the world also experienced a slow-down. The USA grew only 0.3% in April, May and June 2002 when compared to the same months in 2001. The US Federal Reserve made 11 rate cuts over that year in an attempt to stimulate the economy. Whilst in Europe the EU scarcely grew throughout the whole of 2002 and many governments (notably Germany and France) lost control of public finances causing large deficits which broke the terms of the EMU Stability and Growth Pact.

Celtic Tiger 2

After the slowdown in 2001 and 2002, Irish economic growth began to accelerate once again in late 2003 and 2004. The Irish media quickly jumped upon this as an opportunity to document the return of the Celtic Tiger - commonly referred to in the press as the Celtic Tiger 2 and Celtic Tiger Mark 2. In 2004 Irish growth was the highest of the 15 old European states (the EU pre-May 2004) at 5% and a similar figure is forecast for 2005 - these rates contrast with much lower figures (1-3%) for many other European economies, such as Germany, France, and Italy. More edvidence of the return of the Celtic Tiger emerged in late 2004, and early 2005 when Irish unemployment fell to 4.3% [11] (http://www.finfacts.com/irelandbusinessnews/publish/article_1000321.shtml) - the lowest rate in the EU and the government budget returned to surplus.

Causes

The reasons for the resurrection of the Irish economic boom are somewhat controversial within Ireland. There is currently open debate in the country - the skeptics say that recent growth is merely due to a huge increase in house values and catch-up growth in employment in the construction sector, whilst others claim that there are several other factors at play in the new boom. These factors include:

- The soon to be released SSIA government savings scheme has relaxed consumers concerns about spending and thus fuelled retail sales growth. [12] (http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2095-1312882,00.html)

- The continued investment by multi-national firms - Intel has resumed Irish expansion, Google has based major offices in Dublin [13] (http://www.idaireland.com/home/news.aspx?id=9&content_id=85), Abbott Laboratories is building an Irish facility [14] (http://www.idaireland.com/home/news.aspx?id=9&content_id=176) and Bell Labs is to open a facility in the near future [15] (http://www.idaireland.com/home/news.aspx?id=274&content_id=192).

- A successful drive to attract high skill jobs to Ireland - the location of Google and Bell Labs in Ireland is a cornerstone of this new drive. A new state body has been established to promote new science companies in Ireland - Sciences Foundation Ireland. [16] (http://www.entemp.ie/press/2004/20040809.htm)

- A rebound in tourism - after three bad years in the industry caused by Foot and mouth disease and the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York which hit US visitor numbers. [17] (http://www.arts-sport-tourism.gov.ie/pressroom/pr_detail.asp?ID=81)

- A US recovery has boosted Ireland's economy dramatically due to Ireland's close economic ties to the US.

- Recovery of world IT industry - Ireland produces 25% of all European PC's - Dell, IBM, Apple and HP all have sizeable Irish operations.

Challenges and threats ahead

The return of the boom in 2004 has thus far been largely caused by a single industry - the huge construction sector which is only now catching up with the demand caused by the first boom. Many highly regarded international figures and publications such as The Economist have warned of a crash in Irish property prices. Already, rent yields are falling nationwide on residential property and output has now outpaced supply - 2004 saw the construction of 80,000 new homes - compared to the UK's 160,000 - a nation that has 15 times Ireland's population.

Loss of competitiveness

Rising wages, inflation, poor infrastructure, excessive public spending and the accession of eight new Eastern European members to the EU in 2004 are just some of the other threats to the continued competitiveness of the Irish Economy and sustained growth. Irish wages are now substantially above the EU average - particularly in the Dublin region. These pressures will damage low to mid skill jobs, largely in manufacturing. Outsourcing of many professional jobs is beginning to take place also. Poland recently gained several hundred former Irish jobs from the accountancy division of Philips. The government has set up Science Foundation Ireland [18] (http://www.sfi.ie/home/index.asp) to help promote high-skill education and invest in science initiatives to create a Knowledge Economy in Ireland which would lessen the worries that jobs could simply be outsourced to a cheaper location.

Promotion of indigenous industry

One of the major challenges facing Ireland is the successful promotion of indigenous industry. Although Ireland boasts a few large international companies such as CRH, Kerry Group, Elán and Ryanair, these are exceptions rather than the rule. There are very few other companies with over a billion Euros in annual revenue. The government has charged Enterprise Ireland [19] (http://www.enterprise-ireland.com/) with the task of boosting Ireland's indigenous industry. In 2003 the government launched a one-stop-shop website for setting up and running a business in Ireland - it is hoped basis.ie (http://www.basis.ie/) will make starting a business in Ireland easier and quicker.

Over-reliance on foreign energy sources

Another possible threat is Ireland's over-reliance on foreign oil. Ireland for many years curbed dependence on foreign energy sources by developing its peat bogs, building a dam on the River Shannon and developing off shore gas fields. However today the potential for hydroelectricity has been tapped as far as it can be, gas is now in use to the extent it can be and the peat bogs are no longer economical - this has led to an ever-increasing need for oil. One solution is to develop Ireland's huge potential for wind power and to a lesser extent wave power. The world's largest off-shore windfarm is currently in construction off the east coast of the island near Arklow and many remote locations in the west of the country show potential for windfarm development. A report by Sustainable Energy Ireland revealed that if properly developed, Ireland could one day be exporting excess wind power - however at the moment wind power only supplies 5% of Irish electricity.

Spreading the wealth

National_Development_Plan_Ireland.jpg

Like any country that undergoes rapid growth, Ireland's new wealth is not evenly distributed - it is concentrated principally on the east coast surrounding Dublin. The challenge is to spread the new wealth nationwide to remote areas such as Connemara and Donegal [20] (http://www.idaireland.com/home/news.aspx?id=295&content_id=154#spatial). To do this the government has taken three main measures:

- Establishment of a National Development Plan (NDP) [21] (http://www.ndp.ie/newndp/displayer?page=home_tmp) to invest in infrastructure throughout the country.

- Formulation of a National Spatial Strategy [22] (http://www.irishspatialstrategy.ie/) to focus on the development of Gateways and Hubs - towns such as Mullingar, Athlone, and Ennis have been designated as Gateways and Hubs.

- Decentralisation of Government departments to regional centres. This will involve moving 10,000 civil servants out of the capital.

Relative poverty

As in many major cities, despite the boom many communities, particularly in Dublin, are still crime-ridden and in relative poverty. Examples include Ballymun on the city outskirts and the Fatima Mansions in the inner city. Drug use and crime are still major problems in these areas. The government has enlisted Ballymun Regeneration Ltd. (http://www.brl.ie) to regenerate the Ballymun area and move the people into new homes. They began knocking down the Ballymun flats in 2004.

Ireland_income_distribution_chart.gif

Politics and the Celtic Tiger

One of Ireland's most distinguished economists, Professor Dermot McAleese, says that the emergence of the Progressive Democrats in 1985 may have had a more positive influence on the economy than some recognise. He argues the low-tax, pro-business economy we know today is based in large part on PD policies. "They proved that there was a constituency for this, and they gave the intellectual power to it." (The Irish Times, 31 December 2004). In 1989, the Progressive Democrats entered government for the first time in coalition with Fianna Fáil. They began to implement what was viewed as a radical economic agenda, reducing the rate of VAT, income tax and most importantly for fuelling the Celtic Tiger, corporation tax. These controversial policies were so successful that they were continued and expanded by successive governments.

The 1992 election saw gains for the minority parties, at the expense of the centre parties. Fianna Fáil lost 9 seats while Fine Gael lost 10. On the other hand, Labour gained 18 seats (increasing their Dáil representation by 54%), while the Progressive Democrats won 4 seats (increasing their Dáil representation by 67%). A Fianna Fáil-Labour government was formed, but it had a short life time. It was replaced by a Fine Gael-Labour-Democratic Left coalition (the "Rainbow coalition") in 1994.

The 1997 election saw the centre-left Rainbow Coalition compete against the centre-right Fianna Fáil-Progressive Democrat coaltion. Both coalitions appealed to voters with promises of reduced income tax. The election proved to be a reversal of 1992. The centre parties gained seats at the expense of Labour and the Progressive Democrats. The Fianna Fáil-Progressive Democrat coalition formed a government with the support of independent TDs.

The Celtic Tiger was in full swing at this stage. This allowed the government cut the income tax rates to 20% and 42%, Corporation tax was fixed at 12.5% for all companies, and capital gains tax was halved. By reducing corporation tax and capital gains tax more economic activity was generated. This resulted in the government collecting more revenue in total from both of these taxes, even though the actual rates were reduced. The budget surpluses this generated allowed for record levels of spending on health, education, social welfare and infrastructure. However, public opinion is split on whether the government got value for money from these spending increases.

The 2002 election saw the outgoing Fianna Fáil/Progressive Democrat government re-elected. Fianna Fáil were left just short of an overall majority,while the Progressive Democrats doubled their representation from 4 to 8. Labour remained stable and Sinn Féin gained their first significant result in a general election since the foundation of the state. The Green Party gained a threefold increase in seats from 2 to 6 as the growing middle class turned their concerns to the environment and poverty.

Under Bertie Ahern Fianna Fail today remains in an uncertain position. The popularity of Irelands economic growth has been undermined by quality of life issues [congestions, inequality, the environment]and anger over the state of the Health service, as is shown by the relatively poor showing of Fianna Fáil in the 2004 European Elections and local elections where they polled in the low thirties, their lowest since 1927 thanks to a small revival of Labour and Green Party fortunes, and a loss of republican votes to Sinn Fein. In late 2004 Ahern began to realign himself somewhat towards the left in response to this.

References

- The Celtic Tiger: Ireland's Continuing Economic Miracle by Paul Sweeney ISBN 1860761488

- After the Celtic Tiger: Challenges Ahead by Peter Clinch, Frank Convery and Brendan Walsh ISBN 086278767X

- The Celtic Tiger? : The Myth of Social Partnership by Kieran Allen ISBN 0719058481

- The Making of the Celtic Tiger: The Inside Story of Ireland's Boom Economy by Ray Mac Sharry, Joseph O'Malley and Kieran Kennedy ISBN 1856353362

- The End of Irish History? : Critical Approaches to the Celtic Tiger by Colin Coulter, Steve Coleman ISBN 0719062314

- The Celtic Tiger In Distress: Growth with Inequality in Ireland by Peadar Kirby, Peadar Kir ISBN 0333964357

- Can the Celtic Tiger Cross the Irish Border? (Cross Currents) by John Bradley, Esmond Birnie ISBN 1859183123

- Inside the Celtic Tiger: The Irish Economy and the Asian Model (Contemporary Irish Studies) by Denis O'Hearn ISBN 0745312837

Online

- The Celtic Tiger In Distress (http://www.dcu.ie/news/pub/pub4.shtml)

- Celtic Tiger II on way - Business World (http://www.businessworld.ie/livenews.htm?a=1012096;s=rollingnews.htm)

- Celtic Tiger roars again - but not for the poor - The Guardian (http://www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,3604,1321313,00.html)

- Survey: Ireland - The luck of the Irish - Economist Magazine (http://www.economist.com/surveys/showsurvey.cfm?issue=20041016)

- IDA Success Stories (http://www.idaireland.com/home/index.aspx?id=5)

- Tiger, Tiger, Fading Fast, Could other countries replicate Ireland's economic transformation? - Slate (MSN) (http://www.slate.com/id/2111312)