Bloodletting

|

|

Bloodletting (or blood-letting, in modern medicine referred to as phlebotomy) was a popular medical practice from antiquity up to the late 19th century, involving the withdrawal of often considerable quantities of blood from a patient in the belief that this would cure or prevent illness and disease. The practice has been largely abandoned due to its proven ineffectiveness against all but a few conditions.

The term "phlebotomy" is still sometimes used for the taking of blood for laboratory analysis or blood transfusion.

| Contents |

Bloodletting in the ancient world

Bloodletting is one of the oldest medical practices, having been practiced among diverse ancient peoples, including the Greeks, the Egyptians and the Mesopotamians. In Greece, bloodletting was in use around the time of Hippocrates, who mentions bloodletting but in general relied on dietary techniques. Erastistratus, however, theorized that many diseases were caused by plethoras, or overabundances, in the blood, and advised that these plethoras be treated, initially, by exercise, sweating, reduced food intake, and vomiting. Herophilus advocated bloodletting. Archagathus, one of the first Greek physicians to practice in Rome, practiced phlebotomy extensively and gained a most sanguinary reputation.

The popularity of bloodletting in Greece was reinforced by the ideas of Galen, after he discovered the veins and arteries were filled with blood, not air as was commonly believed at the time. There were two key concepts in his system of bloodletting. The first was that blood was created and then used up, it did not circulate and so it could 'stagnate' in the extremities. The second was that humoural balance was the basis of illness or health, the four humours being blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile (relating to the four Greek classical elements of earth, air, fire and water). Galen believed that blood was the dominant humour and the one in most need of control. In order to balance the humours, a physician would either remove 'excess' blood (plethora) from the patient or give them an emetic (to induce vomiting) or diuretic (to induce urination).

Galen created a complex system of how much blood should be removed based on the patient's age, constitution, the season, the weather and the place. Symptoms of plethora were believed to include fever, apoplexy, and headache. The blood to be let was of a specific nature determined by the disease: either arterial or venous, and distant or close to the area of the body affected. He linked different blood vessels with different organs, according to their supposed drainage. For example, the vein in the right hand would be let for liver problems and the vein in the left hand for problems with the spleen. The more severe the disease, the more blood would be let. Fevers required copious amounts of bloodletting.

The Talmud recommended a specific day of the week and days of the month for bloodletting, and similar rules, though less codified, can be found among Christian writings advising which saint's days were favourable for bloodletting. Islamic authors too advised bloodletting, particularly for fevers. The practice was probably passed to them by the Greeks; when Islamic theories became known in the Latin-speaking countries of Europe, bloodletting became more widespread. Together with cautery it was central to Arabic surgery; the key texts Kitab al-Qanum and especially Al-Tasrif li-man 'ajaza 'an al-ta'lif both recommended it. It was also known in Ayurvedic medicine, described in the Susrata Samhita.

Bloodletting in the last millennium

4_transfusion.jpg

Even after the humoral system fell into disuse, the practice was continued by surgeons and barber-surgeons. Though the bloodletting was often recommended by physicians, it was carried out by barbers. This division of labour led to the distinction between physicians and surgeons. The barbershop's red-and-white-striped pole, still in use today, is derived from this practice: the red represents the blood being drawn, the white represents the tourniquet used, and the pole itself represents the stick squeezed in the patient's hand to dilate the veins. Bloodletting was used to 'treat' a wide range of diseases, becoming a standard treatment for almost every ailment, and was practiced prophylactically as well as therapeutically.

The practice continued throughout the Middle Ages but began to be questioned in the 16th century, particularly in northern Europe and the Netherlands. In France, the court and university physicians advocated frequent phlebotomy. In England, the efficacy of bloodletting was hotly debated, declining throughout the 18th century, and briefly revived for treating tropical fevers in the 19th century.

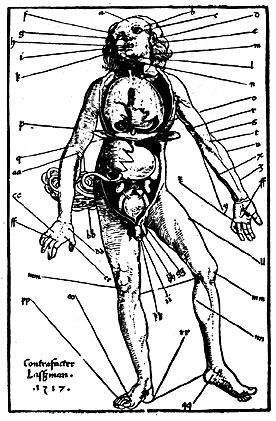

A number of different methods were employed. The most common was phlebotomy or venesection (often called "breathing a vein"), in which blood was drawn from one or more of the larger external veins, such as those in the forearm or neck. In arteriotomy an artery was punctured, although generally only in the temples. In scarification the "superficial" vessels were attacked, often using a syringe, a spring-loaded lancet, or a glass cup that contained heated air, producing a vacuum within. Leeches could also be used; see leeching. The withdrawal of so much blood as to induce syncope (fainting) was considered beneficial, and many sessions would only end when the patient began to swoon.

William Harvey disproved the basis of the practice in 1628, and the introduction of scientific medicine, la méthode numérique, allowed Pierre Louis to demonstrate that phlebotomy was entirely ineffective in the treatment of pneumonia and various fevers in the 1800s. Nevertheless, in 1840 a lecturer at the Royal College of Physicians would still state that "blood-letting is a remedy which, when judiciously employed, it is hardly possible to estimate too highly" and Louis was dogged by the sanguinary Broussais, who could recommend leeches fifty at a time.

Bloodletting was especially popular in the young United States of America, where Benjamin Rush (a signatory of the Declaration of Independence) saw the state of the arteries as the key to disease, recommending levels of blood-letting that were high, even for the time. George Washington was treated in this manner following a horseback riding accident: almost 4 pounds (1.7 litres) of blood was withdrawn, contributing to his death by throat infection in 1799.

One reason for the continued popularity of bloodletting (and purging) was that, while anatomical knowledge, surgical and diagnostic skills increased tremendously in Europe from the 17th century, the key to curing disease remained elusive and the underlying belief was that it was better to give any treatment than nothing at all. The psychological benefit to the patient (a placebo effect) outweighed the physiological problems it caused. As bloodletting lost favour in the 19th century, there was nothing available to replace it in this capacity.

Phlebotomy today

Today the inefficacy of bloodletting for most diseases is well-established. Phlebotomy still has its place in treatment of a few diseases like hemochromatosis and polycythemia. Phlebotomy is still in practice nowadays in hospitals but not in the same manner as stated above. Phlebotomy is now a very specialised skill requiring specific training.

In the past it has been the job of the doctor to withdraw blood from the patient for the purpose of performing blood tests, but the new position of the phlebotomist has been introduced to reduce the work load on doctors. Phlebotomists can be found in almost any hospital or clinics. They are individuals who have been specially trained to carry out venipuncture (puncturing of the vein) and withdraw blood for use in blood tests.

See also

External links

- UCLA Biomedical Library selection on bloodletting (http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/biomed/his/blood/)

- Medical Antiques: Scarification and Bleeding (http://www.medicalantiques.com/medical/Scarifications_and_Bleeder_Medical_Antiques.htm)

- PBS's "Red Gold: The Story of Blood" (http://www.pbs.org/wnet/redgold/basics/bloodletting.html)da:Ĺreladning