Autonomic nervous system

|

|

| Contents [hide] |

Anatomy and Physiology of the A.N.S.

In contrast to the voluntary nervous system, the "involuntary" or autonomic nervous system is responsible for homeostasis, maintaining a relatively constant internal environment by controlling such involuntary functions as digestion, respiration, perspiration, and metabolism, and by modulating blood pressure. Although these functions are generally outside of voluntary control, they are not outside our awareness, and they may be influenced by one's state of mind.

The autonomic nervous system is divided into two subsystems, the sympathetic and the parasympathetic, which work in tandem, either in a synergistic or an antagonistic way. The sympathetic system is responsible for providing responses and energy needed to cope with stressful situations such as fear or extremes of physical activity. In response to such stress, the sympathetic system: raises blood pressure, heart rate, and the blood supply to the skeletal muscles at the expense of the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and skin; dilates both the pupils and the bronchioles, providing improved vision and oxygenation; and generates needed energy by stimulating glycogenolysis in the liver and lipolysis in adipose tissue. In general, it serves to stimulate organs and to mobilize energy.

Between stressful situations, the body needs to rest, recover, and gain new energy. These tasks are under the control of the parasympathetic system, which lowers the heart rate and blood pressure, diverts blood back to the skin and the gastrointestinal tract, contracts the pupils and bronchioles, stimulates salivary gland secretion, and accelerates peristalsis. The parasympathetic system influences organs toward restoration and the saving of energy.

Some anatomists refer to a third, or enteric, system primarily situated in the intestinal walls. It can be modulated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers which are connected to plexuses in the several layers of the walls. However, the enteric nervous system is capable of operating on its own, even after having been severed from input from the SNS and PNS. This is why the enteric nervous system is sometimes referred to as a "second brain." (Hospital Practice, The Enteric Nervous System: A Second Brain, Michael D. Gershon, MD, Columbia University) ([1] (http://www.hosppract.com/issues/1999/07/gershon.htm))

The enteric nervous system regulates secretions of the intestinal glands, regeneration of the intestinal epithelium, and intestinal motility. The ENS is sometimes considered the third part of the autonomic nervous system.

In contrast to the voluntary motor nerves, which consist of only one cell, or neuron, the sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres have both a "preganglionic" and a "postganglionic" nerve cell. They meet at a ganglion, where the nerve impulse is transferred from cell to cell, at a synapse, by the chemical transmitter acetylcholine, or "ACH". ACH is released from the first neuron and binds to a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor on the second. The latter transfers the impulse to an effector cell by releasing a second neurotransmitter. In parasympathetic fibres, the second transmitter is again ACH, while noradrenaline serves as the second transmitter in the sympathetic system. Preganglionic sympathetic fibres also end in the adrenal medulla, which functions as a giant ganglion which, instead of releasing a transmitter into a synapse, releases its second neurotransmitter, noradrenaline or adrenaline, directly into the blood stream.

The cell bodies of preganglionic autonomic nerve cells are situated in the central nervous system. Those of the sympathetic nervous system arise in the thoracal and lumbal segments of the spinal cord. The preganglionic parasympathetic cell bodies are situated in the brain stem (cranial parasympathetic) and in the sacral spinal cord (sacral parasympathetic).

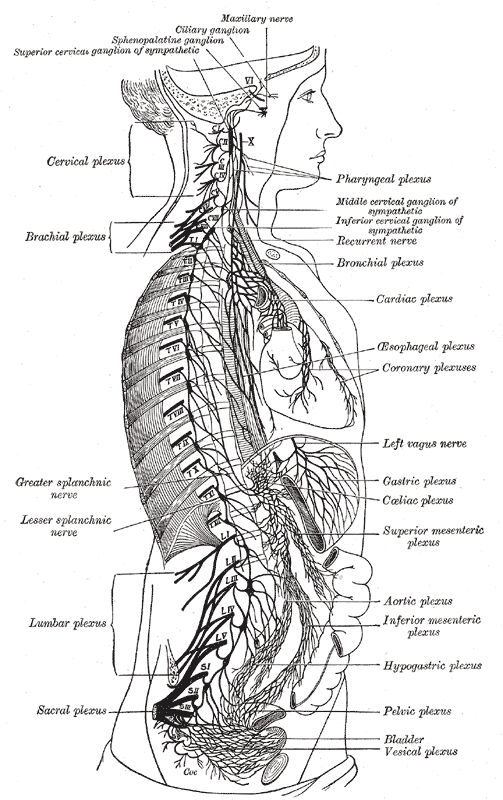

The sympathetic axons build a chain of 22 ganglia, the so-called trunk of the sympathetic nerve, on each side of the spinal column. From these the splanchnic nerves run to the prevertebral ganglia, which lie in front of the aorta, at the level where its unpaired visceral arteries branch off. The left and right trunks of the sympathetic nerve fuse to form an unpaired ganglion in the pelvic area. Organs innervated by sympathetic fibres include the heart, lungs, esophagus, stomach, small and large intestine, liver, gallbladder and genital organs.

These organs are also innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system. The digestive system distal to the lower part of the colon is regulated by the sacral parasympathetic fibres via the pelvic ganglia. The more proximal digestive tract is controlled by the vagus nerve, the largest element of the cranial parasympathetic system. Like those of the vagus, other cranial parasympathetic fibers arise in the brain stem before exiting the skull with various cranial nerves, en route to the cranial parasympathetic ganglia and the innervation of the eye muscles and salivary glands.

Details of Individual Components of the A.N.S.

Figure 1: The right sympathetic chain and its connections with the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic plexuses. (After Schwalbe.)

The peripheral portion of the sympathetic nervous system is characterized by the presence of numerous ganglia and complicated plexuses. These ganglia are connected with the central nervous system by three groups of sympathetic efferent or preganglionic fibers, i. e., the cranial, the thoracolumbar, and the sacral. These outflows of sympathetic fibers are separated by intervals where no connections exist. The cranial and sacral sympathetics are often grouped together owing to the resemblance between the reactions produced by stimulating them and by the effects of certain drugs. Acetylcholine, for example, when injected intravenously in very small doses, produces the same effect as the stimulation of the cranial or sacral sympathetics, while the introduction of adrenalin produces the same effect as the stimulation of the thoracolumbar sympathetics. Much of our present knowledge of the sympathetic nervous system has been acquired through the application of various drugs, especially nicotine which paralyzes the connections or synapses between the preganglionic and postganglionic fibers of the sympathetic nerves. When it is injected into the general circulation all such synapses are paralyzed; when it is applied locally on a ganglion only the synapses occurring in that particular ganglion are paralyzed. Langley, 138 who has contributed greatly to our knowledge, adopted a terminology somewhat different from that used here and still different from that used by the pharmacologists. This has led to considerable confusion, as shown by the arrangement of the terms in the following columns. Gaskell has used the term involuntary nervous system.

| Gray | Langley | Meyer and Gottlieb |

| Sympathetic nervous system | Autonomic nervous system | Vegetative nervous system |

| Cranio-sacral sympathetics | Parasympathetics | Autonomic |

| Oculomotor sympathetics | Tectal autonomics | Cranial autonomics |

| Facial sympathetics | Bulbar autonomics | |

| Glossopharyngeal sympathetics | ||

| Vagal sympathetics | ||

| Sacral sympathetics | Sacral autonomics | Sacral autonomics. |

| Thoracolumbar sympathetics | Sympathetic | Sympathetic. |

| Thoracic autonomic | ||

| Enteric | Enteric | Enteric. |

The Cranial Sympathetics

The cranial sympathetics include sympathetic efferent fibers in the oculomotor, facial, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves, as well as sympathetic afferent in the last three nerves.

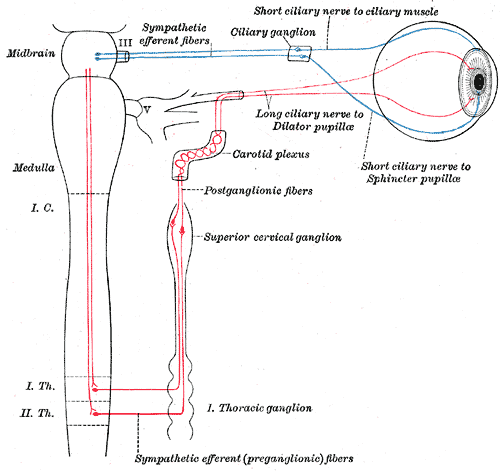

The Sympathetic Efferent Fibers of the Oculomotor Nerve probably arise from cells in the anterior part of the oculomotor nucleus which is located in the tegmentum of the mid-brain. These preganglionic fibers run with the third nerve into the orbit and pass to the ciliary ganglion where they terminate by forming synapses with sympathetic motor neurons whose axons, postganglionic fibers, proceed as the short ciliary nerves to the eyeball. Here they supply motor fibers to the Ciliaris muscle and the Sphincter pupillæ muscle. So far as known there are no sympathetic afferent fibers connected with the nerve.

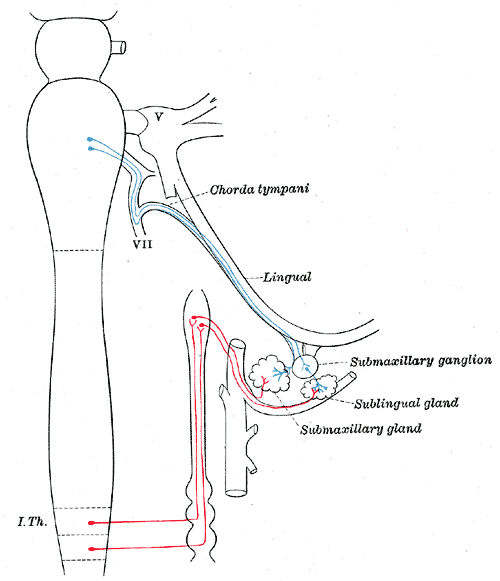

The Sympathetic Efferent Fibers of the Facial Nerve are supposed to arise from the small cells of the facial nucleus. According to some authors the fibers to the salivary glands arise from a special nucleus, the superior salivatory nucleus, consisting of cells scattered in the reticular formation, dorso-medial to the facial nucleus. These preganglionic fibers are distributed partly through the chorda tympani and lingual nerves to the submaxillary ganglion where they terminate about the cell bodies of neurons whose axons as postganglionic fibers conduct secretory and vasodilotar impulses to the submaxillary and sublingual glands. Other preganglionic fibers of the facial nerve pass via the great superficial petrosal nerve to the sphenopalatine ganglion where they form synapses with neurons whose postganglionic fibers are distributed with the superior maxillary nerve as vasodilator and secretory fibers to the mucous membrane of the nose, soft palate, tonsils, uvula, roof of the mouth, upper lips and gums, parotid and orbital glands.

Gray839.png

image:Gray839.png

Figure 2: Diagram of efferent sympathetic nervous system. Blue, cranial and sacral outflow. Red, thoracohumeral outflow. - -, Postganglionic fibers to spinal and cranial nerves to supply vasomotors to head, trunk and limbs, motor fibers to smooth muscles of skin and fibers to sweat glands. (Modified after Meyer and Gottlieb.)

There are supposed to be a few sympathetic afferent fibers connected with the facial nerve, whose cell bodies lie in the geniculate ganglion, but very little is known about them.

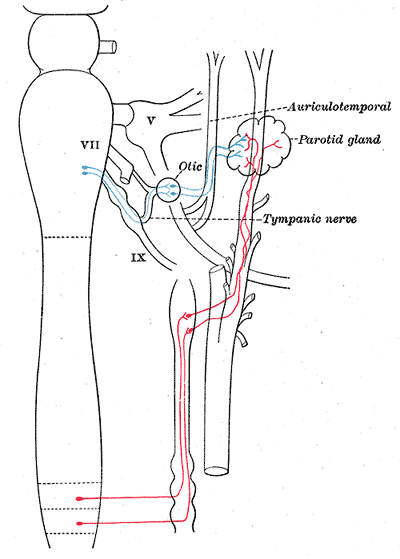

The Sympathetic Afferent Fibers of the Glossopharyngeal Nerve are supposed to arise either in the dorsal nucleus (nucleus ala cinerea) or in a distinct nucleus, the inferior salivatory nucleus, situated near the dorsal nucleus. These preganglionic fibers pass into the tympanic branch of the glossopharyngeal and then with the small superficial petrosal nerve to the otic ganglion. Postganglionic fibers, vasodilator and secretory fibers, are distributed to the parotid gland, to the mucous membrane and its glands on the tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the lower gums.

Sympathetic Afferent Fibers, whose cells of origin lie in the superior or inferior ganglion of the trunk, are supposed to terminate in the dorsal nucleus. Very little is known of the peripheral distribution of these fibers. The Sympathetic Efferent Fibers of the Vagus Nerve are supposed to arise in the dorsal nucleus (nucleus ala cinerea). These preganglionic fibers are all supposed to end in sympathetic ganglia situated in or near the organs supplied by the vagus sympathetics. The inhibitory fibers to the heart probably terminate in the small ganglia of the heart wall especially the atrium, from which inhibitory postganglionic fibers are distributed to the musculature. The preganglionic motor fibers to the esophagus, the stomach, the small intestine, and the greater part of the large intestine are supposed to terminate in the plexuses of Auerbach, from which postganglionic fibers are distributed to the smooth muscles of these organs. Other fibers pass to the smooth muscles of the bronchial tree and to the gall-bladder and its ducts. In addition the vagus is believed to contain secretory fibers to the stomach and pancreas. It probably contains many other efferent fibers than those enumerated above.

Gray841.png

image:Gray841.png

Figure 4 : Sympathetic connections of the sphenopalatine and superior cervical ganglia.

Sympathetic Afferent Fibers of the Vagus, whose cells of origin lie in the jugular ganglion or the ganglion nodosum, probably terminate in the dorsal nucleus of the medulla oblongata or according to some authors in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius. Peripherally the fibers are supposed to be distributed to the various organs supplied by the sympathetic efferent fibers.

The Sacral Sympathetics - The Sacral Sympathetic Efferent Fibers leave the spinal cord with the anterior roots of the second, third and fourth sacral nerves. These small medullated preganglionic fibers are collected together in the pelvis into the nervus erigentes or pelvic nerve which proceeds to the hypogastric or pelvic plexuses from which postganglionic fibers are distributed to the pelvic viscera. Motor fibers pass to the smooth muscle of the descending colon, rectum, anus and bladder. Vasodilators are distributed to these organs and to the external genitalia, while inhibitory fibers probably pass to the smooth muscles of the external genitalia. Afferent sympathetic fibers conduct impulses from the pelvic viscera to the second, third and fourth sacral nerves. Their cells of origin lie in the spinal ganglia.

The Thoracolumbar Sympathetics - The thoracolumbar sympathetic fibers arise from the dorso-lateral region of the anterior column of the gray matter of the spinal cord and pass with the anterior roots of all the thoracic and the upper two or three lumbar spinal nerves. These preganglionic fibers enter the white rami communicantes and proceed to the sympathetic trunk where many of them end in its ganglia, others pass to the prevertebral plexuses and terminate in its collateral ganglia. The postganglionic fibers have a wide distribution. The vasoconstrictor fibers to the bloodvessels of the skin of the trunk and limbs, for example, leave the spinal cord as preganglionic fibers in all the thoracic and the upper two or three lumbar spinal nerves and terminate in the ganglia of the sympathetic trunk, either in the ganglion directly connected with its ramus or in neighboring ganglia. Postganglionic fibers arise in these ganglia, pass through gray rami communicantes to all the spinal nerves, and are distributed with their cutaneous branches, ultimately leaving these branches to join the small arteries. The postganglionic fibers do not necessarily return to the same spinal nerves which contain the corresponding preganglionic fibers. The vasoconstrictor fibers to the head come from the upper thoracic nerves, the preganglionic fibers end in the superior cervical ganglion. The postganglionic fibers pass through the internal carotid nerve and branch from it to join the sensory branches of the various cranial nerves, especially the trigeminal nerve; other fibers to the deep structures and the salivary glands probably accompany the arteries.

The postganglionic vasoconstrictor fibers to the bloodvessels of the abdominal viscera arise in the prevertebral or collateral ganglia in which terminate many preganglionic fibers. Vasoconstrictor fibers to the pelvic viscera arise from the inferior mesenteric ganglia. The pilomotor fibers to the hairs and the motor fibers to the sweat glands apparently have a distribution similar to that of the vasoconstrictors of the skin.

A vasoconstrictor center has been located by the physiologists in the neighborhood of the facial nucleus. Axons from its cells are supposed to descend in the spinal cord to terminate about cell bodies of the preganglionic fibers located in the dorsolateral portion of the anterior column of the thoracic and upper lumbar region.

The motor supply to the dilator pupillæ muscle of the eye comes from preganglionic sympathetic fibers which leave the spinal cord with the anterior roots of the upper thoracic nerves. These fibers pass to the sympathetic trunk through the white rami communicantes and terminate in the superior cervical ganglion. Postganglionic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion pass through the internal carotid nerve and the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve to the orbit where the long ciliary nerves conduct the impulses to the eyeball and the dilator pupillæ muscle. The cell bodies of these preganglionic fibers are connected with fibers which descend from the mid-brain.

Other postganglionic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion are distributed as secretory fibers to the salivary glands, the lacrimal glands and to the small glands of the mucous membrane of the nose, mouth and pharynx. The thoracic sympathetics supply accelerator nerves to the heart. They are supposed to emerge from the spinal cord in the anterior roots of the upper four or five thoracic nerves and pass with the white rami to the first thoracic ganglion, here some terminate, others pass in the ansa subclavia to the inferior cervical ganglion. The postganglionic fibers pass from these ganglia partly through the ansa subclavia to the heart, on their way they intermingle with sympathetic fibers from the vagus to form the cardiac plexus. Inhibitory fibers to the smooth musculature of the stomach, the small intestine and most of the large intestine are supposed to emerge in the anterior roots of the lower thoracic and upper lumbar nerves. These fibers pass through the white rami and sympathetic trunk and are conveyed by the splanchnic nerves to the prevertebral plexus where they terminate in the collateral ganglia. From the celiac and superior mesenteric ganglia postganglionic fibers (inhibitory) are distributed to the stomach, the small intestine and most of the large intestine. Inhibitory fibers to the descending colon, the rectum and Internal sphincter ani are probably postganglionic fibers from the inferior mesenteric ganglion.

The thoracolumbar sympathetics are characterized by the presence of numerous ganglia which may be divided into two groups, central and collateral.

The central ganglia are arranged in two vertical rows, one on either side of the middle line, situated partly in front and partly at the sides of the vertebral column. Each ganglion is joined by intervening nervous cords to adjacent ganglia so that two chains, the sympathetic trunks, are formed. The collateral ganglia are found in connection with three great prevertebral plexuses, placed within the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis respectively.

The sympathetic trunks (truncus sympathicus; gangliated cord) extend from the base of the skull to the coccyx. The cephalic end of each is continued upward through the carotid canal into the skull, and forms a plexus on the internal carotid artery; the caudal ends of the trunks converge and end in a single ganglion, the ganglion impar, placed in front of the coccyx. The ganglia of each trunk are distinguished as cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral and, except in the neck, they closely correspond in number to the vertebræ. They are arranged thus:

- Cervical portion3 ganglia

- Thoracic portion12 ganglia

- Lumbar portion4 ganglia

- Sacral portion4 or 5 ganglia

In the neck the ganglia lie in front of the transverse processes of the vertebræ; in the thoracic region in front of the heads of the ribs; in the lumbar region on the sides of the vertebral bodies; and in the sacral region in front of the sacrum.

Connections with the Spinal Nerves

Communications are established between the sympathetic and spinal nerves through what are known as the gray and white rami communicantes; the gray rami convey sympathetic fibers into the spinal nerves and the white rami transmit spinal fibers into the sympathetic. Each spinal nerve receives a gray ramus communicans from the sympathetic trunk, but white rami are not supplied by all the spinal nerves. White rami are derived from the first thoracic to the first lumbar nerves inclusive, while the visceral branches which run from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves directly to the pelvic plexuses of the sympathetic belong to this category. The fibers which reach the sympathetic through the white rami communicantes are medullated; those which spring from the cells of the sympathetic ganglia are almost entirely non-medullated. The sympathetic nerves consist of efferent and afferent fibers. The three great gangliated plexuses (collateral ganglia) are situated in front of the vertebral column in the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic regions, and are named, respectively, the cardiac, the solar or epigastric, and the hypogastric plexuses. They consist of collections of nerves and ganglia; the nerves being derived from the sympathetic trunks and from the cerebrospinal nerves. They distribute branches to the viscera.

Development

The ganglion cells of the sympathetic system are derived from the cells of the neural crests. As these crests move forward along the sides of the neural tube and become segmented off to form the spinal ganglia, certain cells detach themselves from the ventral margins of the crests and migrate toward the sides of the aorta, where some of them are grouped to form the ganglia of the sympathetic trunks, while others undergo a further migration and form the ganglia of the prevertebral and visceral plexuses. The ciliary, sphenopalatine, otic, and submaxillary ganglia which are found on the branches of the trigeminal nerve are formed by groups of cells which have migrated from the part of the neural crest which gives rise to the semilunar ganglion. Some of the cells of the ciliary ganglion are said to migrate from the neural tube along the oculomotor nerve.

This article is based on an entry from the 1918 edition of Gray's Anatomy, which is in the public domain. As such, some of the information contained herein may be outdated. Please edit the article if this is the case, and feel free to remove this notice when it is no longer relevant.

| Nervous system |

|

Brain - Spinal cord - Central nervous system - Peripheral nervous system - Somatic nervous system - Autonomic nervous system - Sympathetic nervous system - Parasympathetic nervous system |

de:Vegetatives Nervensystem es:Sistema nervioso autónomo he:מערכת העצבים האוטונומית is:Dultaugakerfi nl:Autonoom zenuwstelsel pl:Autonomiczny układ nerwowy ru:Автономная нервная система ja:自律神経系