Australian constitutional crisis of 1975

|

|

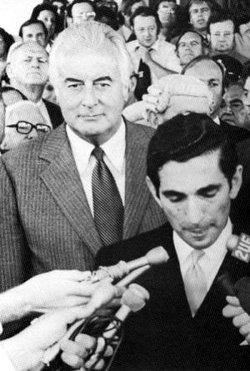

The Australian constitutional crisis of 1975 is generally regarded as the most significant domestic political and constitutional crisis in Australia's history.

The crisis began when the upper house of the Australian Federal Parliament, the Senate, in which the opposition Liberal-National Country Party coalition had a majority, deferred voting on bills that appropriated funds for government expenditure, conditional on the Prime Minister dissolving the House of Representatives and calling an election. Such an action was unprecedented in Australian Federal politics, and has not been attempted since. The government, led by Labor's Gough Whitlam, ignored such calls, and attempted to pressure Liberal senators to support the bill while also exploring alternative means to fund government expenditure.

The impasse continued for some weeks, during which the threat of the government being unable to meet its financial obligations hung over the country. The crisis was resolved in a dramatic fashion on 11 November 1975 when the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, dismissed Whitlam as Prime Minister and appointed his Liberal opponent Malcolm Fraser as caretaker Prime Minister. Kerr did so having secured an undertaking from Fraser that he would seek a dissolution of both the House of Representatives and the Senate, thus precipitating a general election.

Background

The Whitlam government, elected in 1972 after decades of conservative rule, had pioneered several social reforms immediately after gaining office, including the creation of the Medibank universal health care system, the introduction of no-fault divorce legislation, and the abolition of fees for tertiary education. These reforms initially made it popular but the electorate soon became wary of the breakneck pace of reform and Whitlam's "crash through or crash" style. Inexperienced and erratic Ministers made several gaffes; relations with bodies such as the public service (particularly the Treasury) and the trade union movement were often tense, and as the economy was beset by stagflation it came under increasing attack. Desperate to raise revenue, a number of Ministers sought finance through unorthodox channels, triggering the Khemlani loans affair. In 1974, Whitlam called a double dissolution in an effort to gain a government majority in the Senate, but failed. By 1975 the government had become scandal-plagued and unpopular in the electorate.

In this context, two non-Labor State Premiers, when faced with casual vacancies for their states in the Federal Senate (caused by the appointment of one sitting Senator as a judge and the sudden death of another), filled those vacancies with senators who did not strongly support the Labor government. One of these replacement Senators, Albert Patrick Field from Queensland, was a Labor Party member but openly critical of the Whitlam government and was seen as being beholden to the wishes of the strongly anti-Labor Queensland government. The other replacement senator, Cleaver Bunton from New South Wales, was fully independent, being a member of no party at all. The action by Premier Tom Lewis (New South Wales) went against a strong convention under which a senator who dies or resigns mid-term is replaced with a person from the former senator's political party. At the time of the crisis, Senator Field was on leave from the Senate as his appointment was under challenge in the High Court. The number of nominally Labor Senators was thereby reduced, but the Liberal-Country opposition would not provide a "pair" (an informal but well-established tradition whereby whenever a sitting member or Senator is through circumstances outside their control unable to attend and vote, the opposite party reduces its own numbers accordingly by having one of their own members abstain from the vote).

Quoting financial mismanagement as a pretext, the Opposition refused to vote on the passage of the government's budget through the Senate, under the assumption that, having lost the support of Parliament, the Prime Minister was obliged to resign and advise the Governor-General to call an election.

Normally, in Westminster systems, the government is only accountable to the directly-elected lower house, with the upper house being either appointed, hereditary, or indirectly elected. After a confrontation between Lloyd George and the House of Lords, Britain's Parliament Act, 1911 enshrined the principle in Britain that the upper house cannot thwart the wishes of a government with the support of a lower house. Australia's Constitution, however, had provided for a powerful upper house, with wide powers. The constitution had been enacted in 1901, thus pre-dating the Parliament Act. Australian Senators are directly elected, albeit on a rotational basis and in a manner that it is proportionally skewed in favour of states with smaller populations. The Constitution specifically provided that the Senate could not originate bills about finance or expenditure, but it could still technically amend, defer or reject them.

In blocking supply, the Liberals argued that that Whitlam himself had openly flouted conventions, bringing the government into disrepute. His slipshod approach to decision-taking (for example, having decisions taken at informal meetings of his cabinet, rather than at formal meetings of the Executive Council, under the chairmanship of the Governor-General) had already enraged Kerr, a former judge. The Liberals moreover claimed (justifiably, according to opinion polls) that the electorate had tired of the Whitlam government and wished to vote it out.

Whitlam on the other hand had a low regard for the status of the Senate. It had been long-standing Labor policy (implemented in Queensland) to abolish upper houses as anti-democratic. He adamantly insisted that the upper house had no power to dictate terms for the election of the lower house.

The Dismissal

The situation was complicated by the relationship between Kerr and Whitlam. Kerr had long felt that he had been taken for granted and not given the respect due to his office. Originally a Labor sympathiser earlier in his life, Kerr had started to drift towards the conservatives and felt isolated and aloof from the Government.

The precedent had long been established that the Governor-General was expected only to act on advice received from the Prime Minister, and Whitlam confidently assumed this would be the case. However, according to the Constitution, the Governor-General still possessed wide ranging reserve powers to dissolve parliament and sack the government on his own initiative in a time of crisis. Liberal supporters claimed that constitutionally, he had every right to expect a prime minister who had been unable to obtain supply to either resign or seek a parliamentary dissolution. As the government money threatened to run out Kerr came under increasing pressure to act independently.

A precedent had been set in Australia for the use of the reserve powers at a state level in the dismissal of New South Wales Premier Jack Lang by Sir Phillip Game - but in this situation Game had warned Lang that his dismissal was imminent. Kerr was unwilling to warn Whitlam that he was contemplating dismissing him, fearing that Whitlam's reaction would be to request Elizabeth II as Queen of Australia to remove him as Governor-General instead (an unlikely proposition, but constitutionally possible) and thereby involve the monarch in an Australian political crisis. Kerr was also fearful of threats from Fraser that the Opposition would begin publicly criticising Kerr unless he "did his duty".

This promoted Kerr to seek advice from the Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, Sir Garfield Barwick. This action was post facto criticised by Whitlam on two grounds: firstly, since the High Court does not issue advisory opinions, Barwick was not speaking with constitutional authority but only as an individual, and secondly, Barwick was in fact a former Attorney-General in a Liberal Party government and not in an impartial position. Whitlam claimed that he specifically instructed Kerr not to seek Barwick's advice, but Kerr maintained that he did what was necessary to resolve the crisis.

Kerr also met with Opposition Leader Malcolm Fraser. Fraser argued that the Senate represented the displeasure of the Australian people with the government's management; that there was a practical impasse for the government; and, stressing the necessity for action well before government revenue dried up, that if the Governor-General did not act decisively then the Prime Minister could without notice dismiss the Governor-General and maintain the deadlock indefinitely.

On November 11, 1975, stating that there was no prospect of the crisis being resolved otherwise, Kerr dismissed Prime Minister Whitlam and appointed Malcolm Fraser as the caretaker Prime Minister, on the basis that Fraser had promised to pass supply, then immediately advise the Governor-General to dissolve parliament and call a general election. Fraser did so, and Kerr called a general election for December 13, 1975. The Liberal and National Country Party Senators were advised of the situation and they duly voted to pass the Supply Bill, along with the Labor Senators. However the Labor Senators were not yet aware that Whitlam and his government had been dismissed (because Whitlam, plotting to defeat Fraser on the floor of the House of Representatives, had omitted to tell them). In any case it would have been useless for the Labor Senators to vote against supply — all through October and November two independents, Lewis's appointment Cleaver Bunton and Steele Hall, a former Liberal Party but now Liberal Movement Senator from South Australia, had supported the Labor Party — the motions for deferring the Budget bills were passed by 30-29 — an outcome which would have been 31-27 in favour of passing the Budget bills had the Labor Senators tried to reject them on November 11th. Kerr ignored two immediate motions of no confidence in Fraser from the House of Representatives as by the time he received them Parliament had already been dissolved by proclamation.

In the ensuing federal election, the ALP's hurriedly prepared campaign shortsightedly focused entirely on the illegitimacy of the dismissal (with the slogan of "Shame Fraser, Shame"), while the much better organised Coalition focused on Labor's economic management shortcomings. Although some people expected a major backlash against Fraser in favour of Whitlam (who had launched his campaign by calling upon his supporters to 'maintain the rage'), the ALP instead suffered its greatest ever loss (losing 7.4% of its previous vote at the 1974 election) against Fraser's Coalition. This was seen as a popular endorsement of Kerr's actions, although Kerr himself soon became a much reviled figure.

Though it is debatable whether the ALP's 1974-1975 management was sufficient justification for the opposition to break with tradition in blocking supply, it does provide a practical case study for comparison of convention based systems (or even partly convention, partly written constitution-based systems) with more rigid systems such as that used in the United States of America where the 2000 election was largely dependent upon technicality rather than any popular or practical issues.

The crisis is significant in analyzing Westminster systems for the large number of conventions that were broken. Unlike the United States, where legislative-executive relations are spelled out in the constitution, these matters are not explicitly stated in the Constitution or any in other legislation. Under normal circumstances, behaviour is determined by convention and custom. The Australian crisis illustrates how unwritten conventions can be overridden during a crisis and forms an argument for their codification (though one that is not accepted by many prominent Australian constitutional scholars).

It is notable that although the crisis was described as Australia's most dramatic political event since Federation in 1901, it caused no disruption in the services of government; it saw the parties remaining committed to the political and constitutional process by contesting the subsequent election and accepting the result. But it did lead to a constitutional change, passed by referendum in 1977, to require that State Premiers and Parliaments fill Senate vacancies with the nominee of the Party of the original holder of the seat.

In the years afterwards, some Australian republicans have used the crisis as an argument for change, on the basis that Australia's current constitution is flawed over (a) the upper house and it powers with regard to supply and (b) the lack of security of tenure of the Governor-General in dealing with a crisis. No attempts to constitutionally deny the Senate the power to block supply have been put to referendum, despite multiple changes of government since 1975.

It is noteworthy that the convention responsible for deciding on the Constitutional Amendments to be included in the referendum of 1988 rejected an amendment stripping the Senate of the power to block supply. Given that the electoral system makes it unlikely for a government to have majority control of the Senate, the question of whether the Senate could ever block supply again still stands. However, in recent years the balance of power in the Australian Senate has been held by the Australian Democrats who have disavowed ever blocking supply to a government. The Liberal/National Coalition government won control of the Senate in its own right in the elections of 2004, rendering the question temporarily moot.

Fraser and Whitlam have not kept up any enmity and are reconciled to the point where they have, on occasion, spoken jointly on political issues such as the referendum of 1999 as to whether Australia should become a republic.

Journalist Paul Kelly has produced a series of books generally regarded as forming the most comprehensive account of the crisis. His most recent is entitled November 1975. Kelly's conclusions on whose actions were ultimately responsible is interesting: while he criticises both Fraser and Whitlam heavily, and points out the flaws in the Australian constitutional system that made it possible, he ultimately shifts the majority of the blame on Kerr for doing little to encourage a negotiated solution to the crisis.

A dramatised version of events exists in the form of a television mini series, The Dismissal (http://imdb.com/title/tt0085006/), screened in 1983. Amongst those with directing credits are George Miller and Phillip Noyce, with cinematography by Dean Semler.