A Day in the Life

|

|

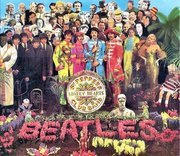

"A Day in the Life" is a song composed by John Lennon and Paul McCartney and recorded for the Beatles album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967. The song was actually a merging of two different, but ultimately complementary, song fragments originally authored independently by Lennon and McCartney. McCartney's fragment was added to the middle of Lennon's. Featuring impressionistic lyrics, innovative production techniques and a complex arrangement including a cacophonous, partially-improvised orchestral crescendo, the song is considered to be one of the most ambitious, influential, and groundbreaking works in pop music history.

| Contents |

Inspiration from a newspaper

Lennon started writing the song while reading the Daily Mail newspaper. Two stories caught his eye; one was about the death of Tara Browne, the heir to the Guinness fortune, and friend of the Beatles, who, on December 18, 1966, drove his Lotus Elan into the back of a parked lorry in Redcliffe Square, South Kensington, London. The other was about a plan to fill 4,000 potholes in the streets of Blackburn, Lancashire.

However, the song did not include a literal description of Browne's fatal accident. Lennon said: "I didn't copy the accident. Tara didn't blow his mind out. But it was in my mind when I was writing that verse. The details of the accident in the song — not noticing traffic lights and a crowd forming at the scene — were similarly part of the fiction." Later, fans eager to locate clues about McCartney's supposed death seized upon this segment of the song as a depiction of his non-existent accident.

Lennon also sang about how the English army "won the war" in the song. Although Lennon is not known to have explained his exact intention, it is thought to be a reference to Lennon's bit part in a movie, How I Won The War, which saw release in October of that year.

McCartney then added the middle section, which was a short piano piece he had been working on previously, with lyrics about a commuter whose uneventful morning routine leads him to drift off into a reverie. McCartney also contributed the line "I'd love to turn you on," which serves as a chorus to the first section of the song. Lennon explained: "I had the bulk of the song and the words, but he contributed this little lick floating around in his head that he couldn't use for anything. I thought it was a damn good piece of work."

McCartney explained that he wrote the piece as a wistful recollection of his younger years. "It was another song altogether, but it happened to fit. It was just me remembering what it was like to run up the road to catch a bus to school, having a smoke and going into class... it was a reflection of my schooldays. I would have a Woodbine (a cheap unfiltered British cigarette) and somebody would speak and I would go into a dream."

On August 27, 1992, Lennon's original handwritten lyrics to the song were auctioned, eventually selling for US$87,000.

Impromptu work in the studio

The Beatles began recording this new song, at that point titled "In the Life Of. . ." on January 19 1967, but at the time, Lennon had not yet decided how he would fill in a glaring gap in the song. The two sections of the song were separated by 24 bars. At first, the Beatles were not sure how to fill this transition; at the conclusion of the recording session for the basic tracks this section consisted of a simple repeated piano chord and the voice of assistant Mal Evans counting the bars. Evans' guide vocal was treated with gradually increasing amounts of echo effect, perhaps an early indication of the bands' desire to have some type of crescendo during this section. The Beatles, particularly Lennon, were enamored of echo effects at this time; Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick recalled: "We'd send a feed from John's vocal mike into a mono tape machine and then tape the output. . . and then feed that back in again. Then we'd turn up the record level until it started to feed back on itself and give a twittery sort of vocal sound."

The 24-bar bridge section ended with the sound of an alarm clock triggered by Evans. The original intent was to edit out the ringing of the alarm clock when the Beatles had filled in the missing section, but because it complemented McCartney's piece very well (particularly because the first line of McCartney's song began "woke up, fell out of bed"), the decision was made to keep the sound. Perhaps it would have remained in any event; Martin later made a cryptic mention that editing it out would have been unfeasible.

Lennon experienced another problem from his unfinished job of composing the song — as he recalled: "And when we came to record the song there was still one word missing from that verse... I knew the line had to go, 'Now they know how many holes it takes to — something — the Albert Hall.' For some reason I couldn't think of the verb. What did the holes do to the Albert Hall? It was [Lennon's friend] Terry Doran who said 'fill' the Albert Hall. And that was it. Then we thought we wanted a growing noise to lead back into the first bit. We wanted to think of a good end and we had to decide what sort of backing and instruments would sound good. Like all our songs, they never become an entity until the very end. They are developed all the time as we go along."

An orchestral "freak out"

The basic track for the song was refined with remixing and additional parts added at recording sessions on January 20 and February 3. By now the original name for the song had been abandoned in favor of the eventual final title. However, the Beatles still had no solution in sight to their missing section of the song, when McCartney had the idea of bringing in a full orchestra and having them "freak out" for the 24-bar middle section. Concern arose, however, that classically-trained musicians would not be able to improvise in this manner, so producer George Martin had to write a loose score for the section — an extended, atonal crescendo — for the musicians to follow (the 41-piece orchestra was also encouraged to improvise within the defined framework).

The orchestral part for the song was recorded on February 10, with McCartney and Martin conducting a 40-piece orchestra. The recording session was completed at a total cost of £367 for the players, considered an extravagance at the time. Martin later described explaining his improvised score to the puzzled orchestra: "What I did there was to write, at the beginning of the twenty-four bars, the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the twenty-four bars, I wrote the highest note each instrument could reach that was near a chord of E major. Then I put a squiggly line right through the twenty-four bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar... Of course, they all looked at me as though I were completely mad."

McCartney also recounted explaining to the orchestra how it was to be done, and the amusing result: "Then I went around to all the trumpet players and said, 'Look, all you've got to do is start at the beginning of the 24 bars and go through all the notes on your instrument from the lowest to the highest — and the highest has to happen on that 24th bar, that's all. So you can blow 'em all in that first thing and then rest, then play the top one there if you want, or you can steady them out.' And it was interesting because I saw the orchestra's characters. The strings were like sheep — they all looked at each other: 'Are you going up? I am!' and they'd all go up together, the leader would take them all up. The trumpeters were much wilder."

McCartney had originally wanted a 90-piece orchestra but this proved unfeasible; the difference was more than made up, however, as the semi-improvised segment was recorded multiple times and eventually four different recordings were overdubbed into a single massive crescendo. For all the chaos of the recording session, the results were a brilliant success; in the final edit of the song the orchestral crescendo is reprised, in even more cacophonous fashion, at the conclusion of the song.

It had been prearranged for this session to be filmed by NEMS Enterprises for use in a planned television special. However, the film was never released in its entirety, although portions of it can be seen in the "A Day In The Life" promotional film, including shots of studio guests like Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Richards, Donovan, Pattie Boyd and Michael Nesmith.

Reflecting the Beatles' taste for experimentation and avant garde at this point, the orchestra players (mostly conservative, middle-aged professional musicians) were decked out in formal dress for the film, but also asked to wear or were given a "fancy dress" piece, leading to different players wearing anything from red noses to fake stick-on nipples. George Martin recalled that the lead violinist performed wearing a gorilla paw, while a bassoon player placed a balloon on the end of his instrument.

The Chord

Following the final orchestral crescendo, the song ends with one of the most famous final chords in music history: all four Beatles, joined by Evans, simultaneously playing an E-major chord on three different pianos. The sound of the final chord was manipulated to ring out for as long as possible (nearly a minute) by increasing the sound level to the tape as the vibration faded out (near the end of the chord the recording levels were turned so high that the sound of papers rustling, a chair squeaking, someone saying "Shhh!" as if they are advising the band members or production staff to keep quiet, and the hum of the Abbey Road studios air conditioning can be heard).

The piano chord was a replacement for a failed vocal experiment: on the evening following the orchestra recording session, the Beatles had originally recorded an ending of their voices humming the chord, but, even after multiple overdubs, found that they wanted something with more impact.

Due to the multiple takes required to perfect the orchestral cacophony and the finishing chord, as well as the Beatles' considerable procrastination in composing the song, the total duration of time spent recording "A Day in the Life" was 34 hours, a rather long time for the production of one song by the Beatles and standing in marked contrast to their earliest work: their first album, Please Please Me, was recorded in its entirety in an incredible 10 hours.

Prior to the release of The Beatles Anthology Volume 3 CD, Paul McCartney was reported to promise a "big surprise" at the end of the disc. Fans speculated it was to be another "new" Beatles song (after the previous "Free As A Bird" and "Real Love"), but instead turned out to be what the liner notes listed as a "final chord" at the end of the CD's final track, "The End". The "final chord" turned out to be the final crashing note of "A Day In The Life" played backwards to the point where it began, then forwards as it normally plays on the "Sgt. Pepper" album (the only clue to the chord's identity was in the album's liner notes listing the recording date in 1967--two years before "The End" was recorded. Also, you can hear the same chair-squeak that was in the Pepper version, which clued other people in to its identity).

Lyrics and alternate versions

Lyrically, the song is actually a fitting together of two entirely different pieces of music, segued together seamlessly to create a powerful and disturbing portrait of a narrator so consumed by the distractions of his everyday life that he is equally unmoved by a tragic car crash, a brutal war film, and a story about potholes, each of which is recounted in the same trivial tone. At the end of the otherwise fairly upbeat Sgt. Pepper album, this sudden note of profound fatalism is rather startling. A sound bite from the song is available.

The song has been released in several versions with minor variations. The version on Sgt. Pepper has its beginning segued from the end of "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (reprise)". The version on the CD release of The Beatles 1967–1970 (the "Blue Album") collection has a clean intro. The Anthology 2 release includes the original basic track, sans orchestra.

Controversy

The song became notorious for its supposedly numerous references to drugs — on June 1, 1967 (two days before the Sgt. Pepper LP was released), the British Broadcasting Corporation announced it was banning "A Day in the Life" from British stations due to the "I'd love to turn you on" line, which according to them, implicitly advocated drug use. Other verses of the song allegedly referring to drugs include the verses "Found my way upstairs and had a smoke / Somebody spoke and I went into a dream". A spokesman for the British Broadcasting Corporation stated: "We have listened to this song over and over again. And we have decided that it appears to go just a little too far, and could encourage a permissive attitude to drug-taking." [1] (http://beatles.ncf.ca/a_day_in_the_life.html)

Lennon and McCartney publicly complained about the ban at a dinner party their manager, Brian Epstein, hosted, to celebrate their new album. Lennon said: "The laugh is that Paul and I wrote this song from a headline in a newspaper. It's about a crash and its victim. How can anyone read drugs into it is beyond me. Everyone seems to be falling overboard to see the word drug in the most innocent of phrases." McCartney said about his part of the song: "The BBC have misinterpreted the song. It has nothing to do with drug taking. It's only about a dream."

McCartney later flatly denied the allegations regarding the verse that got his and Lennon's song banned from British Broadcasting Corporation's stations: "This [line] was the only one on the album written as a deliberate provocation. But what we want to do is to turn you on to the truth rather than on to pot." However, regarding McCartney's segment of the song, Martin said, "At the time I had a strong suspicion that 'went upstairs and had a smoke' was a drug reference. They always used to disappear and have a little puff but they never did it in front of me. They always used to go down to the canteen and Mal Evans used to guard it."

It has been claimed that the BBC's ban has not officially been lifted, but like other former BBC bans it has clearly fallen into abeyance, because the Corporation has played the song quite frequently in recent years. "A Day In The Life" was, tellingly, the last song played by the British offshore pirate station Radio London before it closed down on August 14, 1967 to avoid contravening the Marine Etc. (Broadcasting) Offences Act - pop radio would soon be put into the hands of the BBC, and "Big L" were clearly reflecting a strong feeling at the time that the BBC could never do pop radio in the true, uncensored sense in the way that the much-mourned offshore stations could. [2] (http://www.applecorp.com/aditl/context.htm)

The song also became an integral part of the "Paul Is Dead" hoax, with part of the song falling under suspicion as the depiction of a motor accident which proved fatal for McCartney.

Controversy about the song remained some 34 years later: In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks, a list of songs, including "A Day in the Life", circulated on the internet purportedly from Clear Channel Communications to its affiliates recommending that the listed songs not be played in order to avoid hurting the sensitivities of the American public (it was later revealed that the original list was the work of a few program directors working on their own, and that the list grew and changed as it was circulated). An urban legend was perpetuated that the intent was an officially sanctioned ban on the listed songs, but this has been denied by Clear Channel Communications.

This was one of the Beatles songs that the producer, after the final note of the song, Lennon had George Martin dub in a high pitched tone, which most humans can't hear. Humans can only hear it sometimes if the song is played through powerful speakers. When the tone emits, it drives animals crazy.

A few seconds after this ends, at the end of the album, there is a loop of incomprehensible Beatles studio chatter that was spliced together. This was put there so vinyl copies would play this continuously in the run-out groove, sounding like something went horribly wrong with the record. The chatter on the end was covered by Pink Floyd at the end of their début album "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". They replaced the chatter by some sort of duck quacking in the same melody. Pink Floyd recorded their début at the same time and in the same studio as The Beatles recorded Sgt. Pepper. Both groups visited some of the other groups recording sessions and influenced each other this way.

Vocal melody

Missing image

A_Day_in_the_Life_vocal_melody.PNG

"A Day in the Life" vocal melody and

References

- Rogers, Joyce A. (1996). Amuse Yourself! (http://www.amuseyourself.com/amuse-2000/epitaph/paulisdead/paulisdead.html). Retrieved Sept. 8, 2004.

- The Beatles Studio (http://www.thebeatles.com.hk/songs/details.asp?deTitle=A+Day+In+The+Life). Retrieved Sept. 8, 2004.

- Marcos' Beatles Page (http://www.geocities.com/SunsetStrip/Palms/6797/songs/adayinthelife.html). Retrieved Sept. 8, 2004.

- Ottawa Beatles Site (http://beatles.ncf.ca/a_day_in_the_life.html). Retrieved Sept. 9, 2004.

- The Ultimate Beatles Experience (http://www.geocities.com/~beatleboy1/dba08sgt.html). Retrieved Sept. 8, 2004.

- beatles-discography.com (http://www.beatles-discography.com/beatles_songs_d.html). Retrieved Sept. 8, 2004.

- Lewisohn, Mark, The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Hamlyn, 1998

- The Beatles Anthology, Chronicle, 2000

External links

- Song lyrics (http://frogcircus.org/beatles/sgt_peppers_lonely_hearts_club_band/a_day_in_the_life)

- Alan W. Pollack's analysis of "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club (Reprise)" and "A Day in the Life" (http://www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/DATABASES/AWP/aditl.html)

| Missing image Jk_beatles_paul.jpg Paul McCartney | The Beatles |

|

| ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

History of the Beatles | Long-term influence | British Invasion | Classic rock era | Paul is Dead rumours | Apple Records | George Martin | Geoff Emerick | Brian Epstein | Beatlesque | Discography | Bootlegs | Beatlemania | ||||||