Cancer

|

|

- For other uses, see Cancer (disambiguation).Missing image

Normal_cancer_cell_division_from_NIH.pngWhen normal cells are damaged or old they undergo apoptosis; cancer cells, however, avoid apoptosis.

Cancer is a class of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell division and the ability of these cells to invade other tissues, either by direct growth into adjacent tissue (invasion) or by migration of cells to distant sites (metastasis). This unregulated growth is caused by a series of acquired or inherited mutations to DNA within cells, damaging genetic information that define the cell functions and removing normal control of cell division. These invasive tissues are said to be malignant. The word tumor ("swelling" in Latin) refers to any mass of abnormal tissue, but may be either malignant (cancerous) or benign (noncancerous).

Cancer can cause many different symptoms, depending on the site and character of the malignancy and whether there is metastasis (spread). A definitive diagnosis usually requires the microscopic examination of tissue in the form of a biopsy. Once diagnosed, cancer is usually treated with surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation.

If untreated, most cancers eventually cause death; cancer is one of the leading causes of death in developed countries. Most cancers can be treated and many cured, especially if treatment begins early. Many forms of cancer are associated with environmental factors that are avoidable. Smoking tobacco leads to more cancers than any other environmental factor.

| Contents |

Diagnosing cancer

Most cancers are initially recognized either because signs or symptoms appear or through screening. Neither of these lead to a definitive diagnosis, which usually requires a biopsy. Some cancers are discovered accidentally during medical evaluation of an unrelated problem.

Signs and symptoms

Roughly, cancer symptoms can be divided into three groups:

- Local symptoms: unusual lumps or swelling (tumor), hemorrhage (bleeding), pain and/or ulceration. Compression of surrounding tissues may cause symptoms such as jaundice.

- Symptoms of metastasis (spreading): enlarged lymph nodes, cough and hemoptysis, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), bone pain, fracture of affected bones and neurological symptoms. Although advanced cancer may cause pain, it is usually not the first symptom.

- Systemic symptoms: weight loss, poor appetite and cachexia (wasting), excessive sweating (night sweats), anemia and specific paraneoplastic phenomena, i.e. specific conditions that are due to an active cancer, such as thrombosis or hormonal changes.

Every single item in the above list can be caused by a variety of conditions (a list of which is referred to as the differential diagnosis). Cancer may be a common or uncommon cause of each item.

Biopsy

A cancer may be suspected for a variety of reasons, but the the definitive diagnosis of most malignancies must be confirmed by microscopic examination of the cancerous cells by a pathologist. The procedure of obtaining cells and/or pieces of tissue, and their examination, is referred to as a biopsy. The tissue diagnosis indicates the type of cell that is proliferating, its severity (degree of dysplasia), and its extent and size. Cytogenetic and immunohistochemistry tests may provide information about future behavior of the cancer (prognosis) and best treatment.

Most cancers can be cured if entirely removed. Sometimes this can be accomplished by the biopsy procedure. When the whole mass of abnormal tissue (the "lesion") is removed, the borders of the sample are examined closely to see if all malignant tissue has truly been excised. This is especially common with cancers of the skin.

The nature of the biopsy depends on the organ that is sampled. Many biopsies (such as those of the skin, breast or liver) can happen on an outpatient basis. Biopsies of other organs are performed under anesthesia and require surgery.

Screening

Cancer screening is a test to detect unsuspected cancers in the population. Screening tests suitable for large numbers of healthy people must be relatively affordable, safe, noninvasive procedures with acceptably low rates of false positive results. If signs of cancer are detected, more definitive and invasive followup tests are performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Screening for cancer can lead to earlier diagnosis. Early diagnosis may lead to extended life. A number of different screening tests have been developed. Breast cancer screening can be done by breast self-examination. Screening by regular mammograms detects tumors even earlier than self-examination, and many countries use it to systematic screen all middle-aged women. Colorectal cancer can be detected through fecal occult blood testing and colonoscopy, which reduces both colon cancer incidence and mortality, presumably through the detection and removal of premalignant polyps. Similarly, cervical cytology testing (using the Pap smear) leads to the identification and excision of precancerous lesions. Over time, such testing has been followed by a dramatic reduction of cervical cancer incidence and mortality. Testicular self-examination is recommended for men beginning at the age of 15 years to detect testicular cancer. Prostate cancer can be screened for by a digital rectal exam along with prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood testing.

Screening for cancer is controversial in cases when it is not yet known if the test actually saves lives. The controversy arises when it is not clear if the benefits of screening outweigh the risks of follow-up diagnostic tests and cancer treatments. For example: when screening for prostate cancer, the PSA test may detect small cancers that would never become life threatening, but once detected will lead to treatment. This situation, called overdiagnosis, puts men at risk for complications from unnecessary treatment such as surgery or radiation. Followup procedures used to diagnose prostate cancer (prostate biopsy) may cause side effects, including bleeding and infection. Prostate cancer treatment may cause incontinence (inability to control urine flow) and erectile dysfunction (erections inadequate for intercourse). Similarly, for breast cancer, there have recently been criticisms that breast screening programs in some countries cause more problems than they solve. This is because screening of women in the general population will result in a large number of women with false positive results which require extensive follow-up investigations to exclude cancer, leading to having a high number-to-treat (or number-to-screen) to prevent or catch a single case of breast cancer early.

Cervical cancer screening via the Pap smear has the best cost-benefit profile of all the forms of cancer screening from a public health perspective as, as a cancer, it has clear risk factors (sexual contact), the natural progression of cervical cancer is that it normally spreads slowly over a number of years therefore giving more time for the screening program to catch it early and the test itself is easy to perform and relatively cheap.

For these reasons, it is important that the benefits and risks of diagnostic procedures and treatment be taken into account when considering whether to undertake cancer screening.

Use of medical imaging to search for cancer in people without clear symptoms is similarly marred with problems. There is a significant risk of detection of what has been recently called an incidentaloma - a benign lesion that may be interpreted as a malignancy and be subjected to potentially dangerous investigations.

Types of cancer

Cancer cells within a tumor are the descendants of a single cell, even after it has metastasized. Hence, a cancer can be classified by the type of cell in which it originates and by the location of the cell.

Carcinomas originate in epithelial cells (e.g. the digestive tract or glands). Hematological malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma, arise from blood and bone marrow. Sarcoma arises from connective tissue, bone or muscle. Melanoma arises in melanocytes. Teratoma begins within germ cells.

Adult cancers

In the USA and other developed countries, cancer is presently responsible for about 25% of all deaths1. On a yearly basis, 0.5% of the population is diagnosed with cancer.

For adult males in the United States, the most common cancers are prostate cancer (33% of all cancer cases), lung cancer (13%), colorectal cancer (10%), bladder cancer (7%) and cutaneous melanoma (5%). As a cause of death lung cancer is the most common (31%) cause, followed by prostate cancer (10%), colorectal cancer (10%), pancreatic cancer (5%) and leukemia (4%)1.

For adult females in the United States, breast cancer is the most common cancer (32% of all cancer cases) followed by lung cancer (12%), colorectal cancer (11%), endometrial cancer (6%, uterus) and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (4%). By cause of death, lung cancer is again the most common (27% of all cancer deaths), followed by breast cancer (15%), colorectal cancer (10%), ovarian cancer (6%) and pancreatic cancer (6%)1.

These statistics vary substantially in other countries.

Other cancers not mentioned:

- Epithelial tumors: skin cancer (this is in fact the most common cancer but often not classified as such in health statistics), cervical cancer, anal carcinoma, esophageal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (in the liver), laryngeal cancer, renal cell carcinoma (in the kidneys), stomach cancer, many testicular cancers, and thyroid cancer.

- Hematological malignancies (blood and bone marrow): leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma.

- Sarcomas: osteosarcoma (in bone), rhabdomyosarcoma - in muscles, (including benign moles and dysplastic nevi).

- Miscellaneous origin: brain tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), mesothelioma (in the pleura or pericardium) and teratomas

Childhood cancers

Cancer can also occur in young children and adolescents. Here, the aberrant genetic processes that fail to safeguard against the clonal proliferation of cells with unregulated growth potential occur early in life and can progress quickly.

The age of peak incidence of cancer in children occurs during the first year of life. Leukemia is the most common infant malignancy (30%), followed by the central nervous system cancers and neuroblastoma. The remainder consists of Wilms' tumor, lymphomas, rhabdomyosarcoma (arising from muscle), retinoblastoma, osteosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma1.

Female infants and male infants have essentially the same overall cancer incidence rates, but white infants have substantially higher cancer rates than black infants for most cancer types. Relative survival for infants is very good for neuroblastoma, Wilms' tumor and retinoblastoma, but not for most other types of cancer.

Causes and pathophysiology

Main article: Carcinogenesis

Origins of cancer

Cell division (proliferation) is a physiological process that occurs in almost all tissues and under many circumstances. Normally the balance between proliferation and cell death is tightly regulated to ensure the integrity of organs and tissues. Mutations in DNA that lead to cancer disrupt these orderly processes.

The uncontrolled and often rapid proliferation of cells can lead to either a benign tumor or a malignant tumor (cancer). Benign tumors do not spread to other parts of the body or invade other tissues, and they are rarely a threat to life unless they extrinsically compress vital structures. Malignant tumors can invade other organs, spread to distant locations (metastasize) and become life-threatening.

Molecular biology

Carcinogenesis (meaning literally, the creation of cancer) is the process of derangement of the rate of cell division due to damage to DNA.

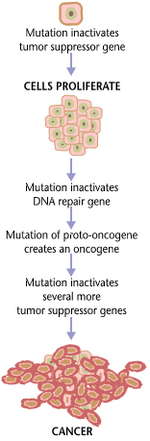

Cancer is, ultimately, a disease of genes. Typically, a series of several mutations is required before a normal cell transforms into a cancer cell. The process involves both proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Proto-oncogenes are involved in signal transduction by coding for a chemical "messenger", produced when a cell undergoes protein synthesis. These messengers, send signals based on the amount of them present to the cell or other cells, telling them to undergo mitosis, in order divide and reproduce. When mutated, they become oncogenes and overexpress the signals to divide, and thus cells have a higher chance to divide excessively. Frustratingly, the chance of cancer cannot be reduced by removing proto-oncogenes from the human genome as they are critical for growth, repair and homeostasis of the body. It is only when they become mutated, that the signals for growth become excessive.

Tumor suppressor genes code for chemical messengers that command cells to slow or stop mitosis in order to allow DNA repair. This is done by special enzymes which detect any mutation or damage to DNA, such that the mistake is not carried on to the next generation. Tumor suppressor genes are usually triggered by signals that DNA damage has occurred. In addition to inhibiting mitosis, they can code for such enzymes themselves, or sending signals to activate such enzymes. However, a mutation can damage the tumor suppressor gene itself, or the signal pathway which activate it, "switching it off". The invariable consequence of this is that DNA repair is hindered or inhibited: DNA damage accumulates without repair, inevitably leading to cancer.

In general, mutations in both types of genes are required for cancer to occur. For example, a mutation limited to one oncogene would be suppressed by normal mitosis control (the Knudson or 1-2-hit hypothesis) and tumor suppressor genes. A mutation to only one tumor suppressor gene would not cause cancer either, due to the presence of many "backup" genes that duplicate its functions. It is only when enough proto-oncogenes have mutated into oncogenes, and enough tumor suppressor genes deactivated or damaged, that the signals for cell growth overwhelm the signals to regulate it, that cell growth quickly spirals out of control.

Mutations can have various causes. Particular causes have been linked to specific types of cancer. Tobacco smoking is associated with lung cancer. Prolonged exposure to radiation, particularly ultraviolet radiation from the sun, leads to melanoma and other skin malignancies. Breathing asbestos fibers is associated with mesothelioma. In more general terms, chemicals called mutagens and free radicals are known to cause mutations. Other types of mutations can be caused by chronic inflammation, as neutrophil granulocytes secrete free radicals that damage DNA. Chromosomal translocations, such as the Philadelphia chromosome, are a special type of mutation that involve exchanges between different chromosomes.

Many mutagens are also carcinogens, but some carcinogens are not mutagens. Examples of carcinogens that are not mutagens include alcohol and estrogen. These are thought to promote cancers through their stimulating effect on the rate cellular mitosis. Faster rates of mitosis increasingly leave less window space for repair enzymes to repair damaged DNA during DNA replication, increasingly the likelihood of a genetic mistake. A mistake made during mitosis can lead to the daughter cells receiving the wrong number of chromosomes, which leads to aneuploidy and may lead to cancer.

Mutations can also be inherited. Inheriting certain mutations in the BRCA1 gene renders a woman much more likely to develop breast cancer and ovarian cancer, mutations in the Rb1 gene predispose to retinoblastoma, and those in the APC gene lead to colon cancer.

Some types of viruses can cause mutations. They play a role in about 15% of all cancers. Tumor viruses, such as some retroviruses, herpesviruses and papillomaviruses, usually carry an oncogene or a gene inhibits normal tumor suppression in their genome.

It is impossible to tell the initial cause for any specific cancer. However, with the help of molecular biological techniques, it is possible to characterize the mutations or chromosomal aberrations within a tumor, and rapid progress is being made in the field of predicting prognosis based on the spectrum of mutations in some cases. For example, up to half of all tumors have a defective p53 gene, a tumor suppressor gene also known as "the guardian of the genome". This mutation is associated with poor prognosis, since those tumor cells are less likely to go into apoptosis (programmed cell death) when damaged by therapy. Telomerase mutations remove additional barriers, extending the number of times a cell can divide. Other mutations enable the tumor to grow new blood vessels to provide more nutrients, or to metastasize, spreading to other parts of the body.

Malignant tumors cells have distinct properties:

- evading apoptosis

- unlimited growth potential (immortalitization)

- self-sufficiency of growth factors

- insensitivity to anti-growth factors

- increased cell division rate

- altered ability to differentiate

- no ability for contact inhibition

- ability to invade neighbouring tissues

- ability to build metastases at distant sites

- ability to promote blood vessel growth (angiogenesis)

A cell that degenerates into a tumor cell does not usually acquire all these properties at once, but its descendant cells are selected to build them. This process is called clonal evolution. A first step in the development of a tumor cell is usually a small change in the DNA, often a point mutation, which leads to a genetic instability of the cell. The instability can increase to a point where the cell loses whole chromosomes, or has multiple copies of several. Also, the DNA methylation pattern of the cell changes, activating and deactivating genes without the usual control. Cells that divide at a high rate, such as epithelials, show a higher risk of becoming tumor cells than those which divide less, for example neurons.

Morphology

Cancer_progression_from_NIH.png

Cancer tissue has a distinctive appearance under the microscope. Among the distinguishing traits are a large number of dividing cells, variation in nuclear size and shape, variation in cell size and shape, loss of specialized cell features, loss of normal tissue organization, and a poorly defined tumor boundary. Immunohistochemistry and other molecular methods may characterise specific markers on tumor cells, which may aid in diagnosis and prognosis.

Biopsy and microscopical examination can also distinguish between malignancy and hyperplasia, which refers to tissue growth based on an excessive rate of cell division, leading to a larger than usual number of cells but with a normal orderly arrangement of cells within the tissue. This process is considered reversible. Hyperplasia can be a normal tissue response to an irritating stimulus, for example callus.

Dysplasia is an abnormal type of excessive cell proliferation characterized by loss of normal tissue arrangement and cell structure. Often such cells revert back to normal behavior, but occasionally, they gradually become malignant.

The most severe cases of dysplasia are referred to as "carcinoma in situ." In Latin, the term "in situ" means "in place", so carcinoma in situ refers to an uncontrolled growth of cells that remains in the original location and shows no propensity to invade other tissues. Nevertheless, carcinoma in situ may develop into an invasive malignancy and is usually removed surgically, if possible.

Heredity

Most forms of cancer are "sporadic", and have no basis in heredity. There are, however, a number of recognised syndromes of cancer with a hereditary component. Examples are:

- breast cancer and ovarian cancer in female carriers of BRCA1

- tumors of various endocrine organs in multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN types 1, 2a, 2b)

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome (various tumors such as osteosarcoma, breast cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, brain tumors) due to mutations of p53

- Turcot syndrome (brain tumors and colonic polyposis)

- Familial adenomatous polyposis an inherited mutation of the APC gene that leads to early onset of colon carcinoma.

Environment and diet

Cancer_smoking_lung_cancer_correlation_from_NIH.png

The most consistent finding, over decades of research, is the strong association between tobacco use and cancers of many sites. Hundreds of epidemiological studies have confirmed this association. Further support comes from the fact that lung cancer death rates in the United States have mirrored smoking patterns, with increases in smoking followed by dramatic increases in lung cancer death rates and, more recently, decreases in smoking followed by decreases in lung cancer death rates in men. Up to half of all cancer cases can be attributed to smoking, diet, and environmental pollution.

Treatment of cancer

Cancer can be treated by surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy or other methods. The choice of therapy depends upon the location and grade of the tumor and the stage of the disease, as well as the general state of the patient (performance status). A number of experimental cancer treatments are also under development.

Complete removal of the cancer without damage to the rest of the body is the goal of treatment. Sometimes this can be accomplished by surgery, but the propensity of cancers to invade adjacent tissue or to spread to distant sites by microscopic metastasis often limits its effectiveness. The effectiveness of chemotherapy is often limited by toxicity to other tissues in the body. Radiation can also cause damage to normal tissue.

Because "cancer" refers to a class of diseases, it is unlikely that there will ever be a single "cure for cancer" any more than there will be a single treatment for all infectious diseases.

Surgery

If the tumor is localized, surgery is often the preferred treatment. Example procedures include mastectomy for breast cancer and prostatectomy for prostate cancer. The goal of the surgery can be either the removal of only the tumor, or the entire organ. Since a single cancer cell can grow into a sizable tumor, removing only the tumor leads to a greater chance of recurrence. A margin of healthy tissue is often resected to make sure all cancerous tissue is removed.

In addition to removal of the primary tumor, surgery is often necessary for staging, e.g. determining the extent of the disease and whether there has been metastasis to regional lymph nodes. Staging determines the prognosis and the need for adjuvant therapy.

Occasionally, surgery is necessary to control symptoms, such as spinal cord compression or bowel obstruction. This is referred to as palliative treatment.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the treatment of cancer with drugs ("anticancer drugs") that can destroy cancer cells. It interferes with cell division in various possible ways, e.g. with the duplication of DNA or the separation of newly formed chromosomes. Most forms of chemotherapy target all rapidly dividing cells and are not specific for cancer cells. Hence, chemotherapy has the potential to harm healthy tissue, especially those tissues that have a high replacement rate (e.g. intestinal lining). These cells usually repair themselves after chemotherapy.

Because some drugs work better together than alone, two or more drugs are often given at the same time. This is called "combination chemotherapy"; most chemotherapy regimens are given in a combination.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is the use of immune mechanisms against tumors. These are used in various forms of cancer, such as breast cancer (trastuzumab/Herceptin®) but also in leukemia (gemtuzumab ozogamicin/Mylotarg®). The agents are monoclonal antibodies directed against proteins that are characteristic to the cells of the cancer in question, or cytokines that modulate the immune system's response.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy, X-ray therapy, or irradiation) is the use of a certain type of energy (called ionizing radiation) to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. Radiation therapy injures or destroys cells in the area being treated (the "target tissue") by damaging their genetic material, making it impossible for these cells to continue to grow and divide. Although radiation damages both cancer cells and normal cells, most normal cells can recover from the effects of radiation and function properly. The goal of radiation therapy is to damage as many cancer cells as possible, while limiting harm to nearby healthy tissue.

Radiation therapy may be used to treat almost every type of solid tumor, including cancers of the brain, breast, cervix, larynx, lung, pancreas, prostate, skin, spine, stomach, uterus, or soft tissue sarcomas. Radiation can also be used to treat leukemia and lymphoma (cancers of the blood-forming cells and lymphatic system, respectively). Radiation dose to each site depends on a number of factors, including the type of cancer and whether there are tissues and organs nearby that may be damaged by radiation.

Hormonal suppression

The growth of nearly all tissues, including cancers, can be accelerated or inhibited by providing or blocking certain hormones. This allows an additional method of treatment for many cancers. Common examples of hormone-sensitive tumors include certain types of breast, prostate, and thyroid cancers. Removing or blocking estrogen, testosterone, or TSH, respectively, is often an important additional treatment.

Treatment trials

Clinical trials, also called research studies, test new treatments in people with cancer. The goal of this research is to find better ways to treat cancer and help cancer patients. Clinical trials test many types of treatment such as new drugs, new approaches to surgery or radiation therapy, new combinations of treatments, or new methods such as gene therapy.

A clinical trial is one of the final stages of a long and careful cancer research process. The search for new treatments begins in the laboratory, where scientists first develop and test new ideas. If an approach seems promising, the next step may be testing a treatment in animals to see how it affects cancer in a living being and whether it has harmful effects. Of course, treatments that work well in the lab or in animals do not always work well in people. Studies are done with cancer patients to find out whether promising treatments are safe and effective.

Patients who take part may be helped personally by the treatment(s) they receive. They get up-to-date care from cancer experts, and they receive either a new treatment being tested or the best available standard treatment for their cancer. Of course, there is no guarantee that a new treatment being tested or a standard treatment will produce good results. New treatments also may have unknown risks, but if a new treatment proves effective or more effective than standard treatment, study patients who receive it may be among the first to benefit.

Complementary and alternative medicine

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments are the diverse group of medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be effective by the standards of conventional medicine. Some non-conventional treatment methods are used to "complement" conventional treatment, to provide comfort or lift the spirits of the patient, while others are offered as alternatives to be used instead of conventional treatments in hope of curing the cancer.

Common complementary measures include prayer or psychological approaches such as "imaging." Many people feel these approaches benefit them, but most have not been scientifically proven and therefore face skepticism.

A wide range of alternative treatments have been offered for cancer over the last century. The appeal of alternative cures arises from the daunting risks, costs, or potential side effects of many conventional treatments, or in the limited prospect for cure. Proponents of these therapies are unable or unwilling to demonstrate effectiveness by conventional criteria. Alternative treatments have included special diets or dietary supplements (e.g., the "grape diet" or megavitamin therapy), electrical devices (e.g., "zappers"), specially formulated compounds (e.g., laetrile), unconventional use of conventional drugs (e.g., insulin), purges or enemas, or physical manipulations of the body. Some of these treatments meet all the criteria for fraud or magic. Collectively they are referred to by skeptics as cancer quackery. An extensive, explanatory catalog of these treatments is available at Quackwatch [1] (http://www.quackwatch.org/00AboutQuackwatch/altseek.html). Almost all physicians recommend against using these modalities as sole treatment for potentially fatal conditions such as cancer.

Epidemiology

In some Western countries, such as the USA1 and the UK2, cancer is overtaking cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of death. In many Third World countries cancer incidence (insofar as this can be measured) appears much lower, most likely because of the higher death rates due to infectious disease or injury. With the increased control over malaria and tuberculosis in some Third World countries, incidence of cancer is expected to rise; this is termed the iceberg phenomenon in epidemiological terminology.

Cancer epidemiology closely mirrors risk factor spread in various countries. Hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer) is rare in the West but is the main cancer in China and neighboring countries, most likely due to the endemic presence of hepatitis B in that population. Similarly, with tobacco smoking becoming more common in various Third World countries, lung cancer incidence has increased in a parallel fashion.

Prevention

Cancer prevention is defined as active measures to decrease the incidence of cancer. This can be accomplished by avoiding carcinogens or altering their metabolism, pursuing a lifestyle or diet that modifies cancer-causing factors and/or medical intervention (chemoprevention, treatment of premalignant lesions).

Much of the promise for cancer prevention comes from observational epidemiologic studies that show associations between modifiable life style factors or environmental exposures and specific cancers. Evidence is now emerging from randomized controlled trials designed to test whether interventions suggested by the epidemiologic studies, as well as leads based on laboratory research, actually result in reduced cancer incidence and mortality.

Examples of modifiable cancer risk include alcohol consumption (associated with increased risk of oral, esophageal, breast, and other cancers), physical inactivity (associated with increased risk of colon, breast, and possibly other cancers), and being overweight (associated with colon, breast, endometrial, and possibly other cancers). Based on epidemiologic evidence, it is now thought that avoiding excessive alcohol consumption, being physically active, and maintaining recommended body weight may all contribute to reductions in risk of certain cancers; however, compared with tobacco exposure, the magnitude of effect is modest or small and the strength of evidence is often weaker. Other lifestyle and environmental factors known to affect cancer risk (either beneficially or detrimentally) include certain sexual and reproductive practices, the use of exogenous hormones, exposure to ionizing radiation and ultraviolet radiation, certain occupational and chemical exposures, and infectious agents.

Diet and cancer

The consensus on diet and cancer is that obesity increases the risk of acquiring cancer. Particular dietary practices often explain differences in cancer incidence in different countries (e.g. gastric cancer is more common in Japan, while colon cancer is more common in the United States). Studies have shown that immigrants develop the risk of their new country, suggesting a link between diet and cancer rather than a genetic basis.

Despite frequent reports of particular substances (including foods) having a beneficial or detrimental effect on cancer risk, few of these have an established link to cancer. These reports are often based on studies in cultured cell media or animals. Public health recommendations cannot be made on the basis of these studies until they have been validated in an observational (or occasionally a prospective interventional) trial in humans.

The case of beta-carotene provides an example of the necessity of randomized clinical trials. Epidemiologists studying both diet and serum levels observed that high levels of beta-carotene, a precursor to vitamin A, were associated with a protective effect, reducing the risk of cancer. This effect was particularly strong in lung cancer. This hypothesis led to a series of large randomized trials conducted in both Finland and the United States (CARET study) during the 1980s and 1990s. This study provided about 80,000 smokers or former smokers with daily supplements of beta-carotene or placebos. Contrary to expectation, these tests found no benefit of beta-carotene supplementation in reducing lung cancer incidence and mortality. In fact, the risk of lung cancer was slightly, but significantly, increased in smokers, leading to an early termination of the study3.

Other chemoprevention agents

Daily use of tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, for up to 5 years, has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of developing breast cancer in high-risk women by about 50%. Cis-retinoic acid also has been shown to reduce risk of second primary tumors among patients with primary head and neck cancer. Finasteride, a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, has been shown to lower the risk of prostate cancer. Other examples of drugs that show promise for chemoprevention include COX-2 inhibitors (which inhibit a cyclooxygenase enzyme involved in the synthesis of proinflammatory prostaglandins).

Cancer vaccines

Considerable research effort is now devoted to the development of vaccines (to prevent infection by oncogenic infectious agents, as well as to mount an immune response against cancer-specific epitopes) and to potential venues for gene therapy for individuals with genetic mutations or polymorphisms that put them at high risk of cancer. No cancer vaccines are presently in use, and most of the research is still in its initial stages.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing for high-risk individuals, with enhanced surveillance or prophylactic surgery for those who test positive, is already available for certain types of cancer, including breast and ovarian cancer.

Coping with cancer

Many local organizations offer a variety of practical and support services to people with cancer. Support can take the form of support groups, counseling, advice, financial assistance, transportation to and from treatment, or information about cancer. Neighborhood organizations, local health care providers, or area hospitals are a good place to start looking.

While some people are reluctant to seek counseling, studies show that having someone to talk to reduces stress and helps people both mentally and physically. Counseling can also provide emotional support to cancer patients and help them better understand their illness. Different types of counseling include individual, group, family, self-help (sometimes called peer counseling), bereavement, patient-to-patient, and sexuality.

Many governmental and charitable organizations have been established to help patients cope with cancer. These organizations often are involved in cancer prevention, cancer treatment, and cancer research. Examples include: American Cancer Society, BC Cancer Agency, Cancer Research UK, Canadian Cancer Society, International Agency for Research on Cancer and the National Cancer Institute (US).

Social impact

Cancer has a reputation for being a deadly disease. While this certainly applies to certain particular types, this is otherwise a generalization. Some types of cancer have a prognosis that is substantially better than nonmalignant diseases such as heart failure and stroke.

Progressive and disseminated malignant disease has a substantial impact on a cancer patient's quality of life, and many cancer treatments (such as chemotherapy) may have severe side-effects. In the advanced stages of cancer, many patients need extensive care, affecting family members and friends. Palliative care solutions may include permanent or "respite" hospice nursing.

Cancer research

Cancer research is the intense scientific effort to understand disease processes and discover possible therapies. While understanding of cancer has increased exponentially since the last decades of the 20th century, radically new therapies are only discovered and introduced gradually.

Inhibitors of tyrosine kinases (imatinib and gefitinib) in the late 1990s were considered a major breakthrough; these interfere specifically with tumor-specific proteins. Monoclonal antibodies have proven to be another major step in oncological treatment.

See also

Template:Wiktionary Template:Commons

References

- Note 1: Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:10-30. Fulltext (http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/55/1/10). PMID 15661684.

- Note 2: Cancer: Number one killer (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/1015657.stm) (9 November, 2000). BBC News online. Retrieved 2005-01-29.

- Note 3: Questions and Answers About Beta Carotene Chemoprevention Trials (http://cis.nci.nih.gov/fact/4_13.htm)

External links

- The World Health Organisation's cancer site (http://www.who.int/cancer/en/) A review of worldwide strategies for the prevention and treatment of cancer.

- US National Cancer Institute (http://www.cancer.gov) Government organization for research and treatment

- American Cancer Society (http://www.americancancersociety.org) Patient advocate group

- Cancer Medicine, 6th Edition (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?call=bv.View..ShowTOC&rid=cmed.TOC&depth=2) Textbook

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (http://www.nccn.org) - has free guidelines for professionals and many pages of quality information for patients with all types of cancers

- American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) (http://www.aicr.org/) - purports to be "the [United States'] leading charity in the field of diet, nutrition and cancer", supporting research into dietary methods for the prevention and treatment of cancer in addition to offering educational resources.

- Acor.org (http://www.acor.org) - Association of Cancer Online Resources

- Cancer (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/cancer.html) from MedlinePlus - provides links to news, general sites, diagnosis, treatment and alternative therapies, clinical trials, research, related issues, organizations, other MedlinePlus Cancers Topics (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/cancers.html) and Living with Cancer (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/cancerlivingwithcancer.html), and more. Also, links to pre-formulated searches of the MEDLINE/PubMed database for recent research articles.ca:Càncer

cs:Rakovina da:Kræft de:Krebs (Medizin) eo:Kancero es:Cáncer fi:Syöpä fr:Cancer he:סרטן (מחלה) id:Kanker it:Tumore ja:悪性腫瘍 lt:Vėžys (liga) ms:Penyakit Barah hu:Rák (betegség) nl:Kanker no:Kreft pl:Nowotwór złośliwy pt:Cancro (tumor) ru:Рак (заболевание) sv:Cancer tr:Kanser zh-cn:肿瘤 zh-tw:腫瘤 vi:ung thư