Vermicompost

|

|

Vermicompost (or worm compost) is produced by feeding kitchen scraps and shredded newspaper to worms. It is one of several different methods of composting.

The earthworm most often to be found in the compost heap is Eisenia foetida or the Brandling worm, also known as the Tiger worm or Red Wriggler. This species is only rarely found in soil and is adapted to the special conditions in rotting vegetation, compost and manure piles. These may arrive naturally, or can be introduced. They are available from mail-order suppliers, or from angling shops where they are sold as bait. Small scale vermicomposting is well suited to turning kitchen wastes into high quality soil where space is limited.

A healthy vermicomposting system hosts many other organisms besides worms. These include certain kinds of insects, molds, and bacteria. The composting process and the relationship between these organisms is poorly understood.

| Contents |

Managing a Vermicomposting Bin

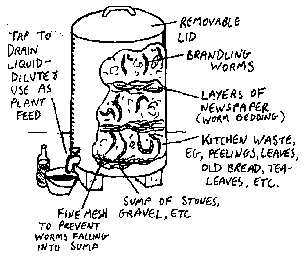

Worm composting can be practised on a small scale in a special bin as shown in the picture. An alternative type of bin is the continuous flow vermicomposting bin, where compost and "brown matter" is added on top. Composted material and excess water escapes out a grate on the bottom of the bin. This allows for easier maintenance of moisture levels, since water will not be able to collect or pool. It also ensures that the composted material does not build up and obviates the need to periodically empty the whole bin.

When beginning a bin, as many composting worms as available should be added to moist bedding created from shredded newspaper and/or potting compost. Quantities of kitchen waste appropriate for the worm population can be added to the bin daily or weekly. If too much kitchen waste is added for the worms to process, the waste will putrify. A balance between "green matter" such as kitchen scraps and "brown matter" such as shredded newspaper for bedding must be maintained in order for the worms to do their work. This balance should be approximately 1:2, green, fresh kitchen type scraps to brown matter, such as leaves, straw or newspaper. Covering the kitchen scraps with bedding has the added benefit of reducing odor and insect problems.

Although proteins such as fats and meat scraps can be processed by a vermicompost bin, doing so tends to attract scavengers and should probably be avoided. Worms are unable to break down bone or synthetic material. Fecal material of omnivores and carnivores is unsuitable for composting due to the dangerous microorganisms it contains, though thermophilic composting or other applied heat can mitigate this problem. People have reports taking cow, rabbit or goat manure, and using it to help start up the bin. If done, this should be used in small quantities. If you are vermicomposting inside your home, you will want to avoid manure, as it may smell. Dairy products have this smelly effect as well.

Over the long term, care should be taken to maintain optimum moisture levels and pH. In a non-continuous-flow bin, excess liquid can be drained via a tap and used as plant food. A continuous flow bin will not retain excess liquid, though it requires extra water to be added to keep the bedding moist. Too many citrus peels in the material to be composted can cause excessive acidity. Adding an occasional handful of lime will mitigate excess acidity.

Worms and vermicomposting work best in a cool, damp, dark environment. The bin should be kept out of direct sunlight and ideally stay at a temperature of around 65 degress Fahrenheit/18 degrees Celsius. The temperature should never fall below freezing (32 F/0 C), as the worms cannot survive such low temperatures. For cooler climates where vermicomposting is being done outside, some people report success combining thermophilic composting methods and vermicomposting during the colder winter months.

Worms as well as other microorganisms in the composting process require oxygen, so the bin must "breathe". This can be accomplished by regularly removing the composted material, adding holes to a composting bin, or using a continuous-flow bin. If insufficient oxygen is available, the compost will become anaerobic. This will provide a host environment for a different type of decay process which produces a strong odor offensive to most people. This type of decay is found in swamps and bogs and is responsible for the stench sometimes found in these environments.

Some Tips for a successful Bin are: Avoid grass clipping or other plant products that have been sprayed with pesticides. In a small bin, this includes banana peels. They can kill everything in the bin, if heavily sprayed. The ideal level of moisture inside your bin is similar to that of a wrung-out sponge. Not burying fruits can attract fruit flies.If your bin smells, it probably is too wet, as mentioned above, or you have put in too much kitchen waste. At first, feed the worms approximately 1/2 their body weight in kitchen scraps a day, maximum. After they have established themselves, you can feed them up to their entire body weight. To speed the process, occasionally turn your compost over, mixing it up.

Note: Red Wiggler worms are native to California, but not to other areas of the country. In some sections of the country, they are an invasive species, so please avoid dumping them into your garden with the compost. They can have the effect of displacing the native worms.

Vermicompost Properties

Worm compost is usually too rich for use as a seed compost, but is useful as a top dressing or an addition to potting composts. Some types of pitted seeds are also reportedly easier to germinate when placed in vermicompost for several months.

Vermicompost is beneficial for soil in three ways:

- It improves the physical structure of the soil.

- It improves the biological properties of the soil (enrichment of micro-organisms, addition of growth hormones such as auxins and gibrellic acid, and addition of enzymes, such as phosphates, cellulase, etc.).

- It attracts deep-burrowing earthworms already present in the soil.

See also

- Container composting

- German mound

- Leaf mold

- Spent mushroom compost

- Sheet composting

- High fibre composting

External Links

- Worm Digest (http://www.wormdigest.org/) - includes articles on vermicomposting, links to suppliers and a discussion board

- Vermicomposting discussion board (http://www.worms.com/phpbb)

- Worms Eat My Garbage (ISBN 0942256107), by Mary Appelhof. A "how-to" book on starting and maintaining a vermicomposting bin.

- The Soil Underground: composting and vermicomposting forums (http://thesoilunderground.com)