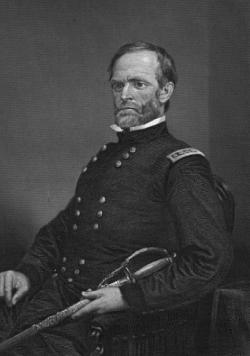

William Tecumseh Sherman

|

|

William_Tecumseh_Sherman.jpg

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 – February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, and author. He served as a general in the United States Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving both recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy and criticism for the harshness of the "scorched earth" policies he implemented in dealing with the enemy. British military historian Liddell Hart famously declared that Sherman was "the first modern general." (See also Total war.)

| Contents |

Early life

Named Tecumseh after the famous chief of the Shawnee tribe, Sherman was born in Lancaster, Ohio. His father, Judge Charles R. Sherman, died when he was nine years old. His younger brother John Sherman would later become a U.S. Senator and the sponsor of the Sherman Antitrust Act. William was raised by a Lancaster neighbor, attorney Thomas Ewing, a prominent member of the Whig Party who served as a Senator from Ohio and as U.S. Secretary of the Interior. Ewing secured the appointment of the 16 year old Sherman as a cadet in the United States Military Academy at West Point, from which he graduated sixth in his class of 1840. He entered the army as a second lieutenant and saw action in Florida in the fight against the Seminole tribe. During the Mexican American War, Sherman performed administrative duties while stationed in California. In 1850 he married Thomas Ewing's daughter, Eleanor Boyle Ewing. Three years later he resigned his military commission and became president of a bank in San Francisco. Sherman's arrival in San Francisco was indicative of the turmoil of his time in the West: he survived not one but two shipwrecks and floated through the Golden Gate on the scraps of a foundering lumber schooner.1 Sherman eventually found himself suffering from stress-related asthma thanks to the city's brutal financial climate.2 Late in life, regarding his time in real estate speculation-mad San Francisco, Sherman recalled: I can handle a hundred thousand men in battle, and take the City of the Sun, but am afraid to manage a lot in the swamp of San Francisco.3

Sherman's bank failed during the financial panic of 1857 and he was forced to accept a job as the first president of the Louisiana Military Seminary, a position offered to him by two of his Southern army friends: P.G.T. Beauregard and Braxton Bragg. Ironically, that institution later became Louisiana State University. Thus, the first president of what is now one of the most prestigious and beloved Southern universities was a Yankee general who would later be remembered as one of the most hated men in the South. After the outbreak of the American Civil War, Sherman resigned the presidency of the Seminary and returned to the North. In April, 1861 he became president of a railroad based in St. Louis, a position he held for less than two months before being called to Washington.

Reaction to secession

On hearing of South Carolina's secession, Sherman presciently observed to a southern friend before going north to serve in the Union Army:

- You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing!

- You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it ...

- Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth -- right at your doors.

- You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.

Service to the Union

Beauregard and Bragg both became Confederate generals during the Civil War. Sherman accepted a commission as a colonel in the U.S. Army and was one of the few Union officers to distinguish themselves at the First Battle of Bull Run, though the disastrous Union defeat led Sherman to question his own judgment as an officer and to request that President Abraham Lincoln relieve him of independent command, which Lincoln refused to do, promoting him instead to Brigadier General in charge of a military department in Louisville, Kentucky. During his time in Louisville, Sherman went through a personal crisis that would today be described as a "nervous breakdown." At a time when Sherman was probably working too hard, as well as drinking and smoking too much, he suffered from a personal collapse which made it necessary for him to go home to Ohio to recuperate. He quickly returned to the service and just six months later performed brilliantly and bravely as Major General under the command of Ulysses S. Grant at the Battle of Shiloh on April 1862. He suffered two slight wounds during that two-day battle in west Tennessee and had four horses shot from under him.

Sherman developed close personal ties to Grant during the two years they served together. At one point, not long after the Battle of Shiloh, Sherman persuaded Grant not to resign from the army, despite the serious difficulties he was having with his commander, General H. W. Halleck. The careers of both officers ascended considerably after that time. They shared in the victories at Vicksburg in July 1863 and Lookout Mountain, in Chattanooga. In later years Sherman said simply, "Grant stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk. Now we stand by each other always."

When Lincoln called Grant east in the spring of 1864 to take command of all Union armies, Grant appointed Sherman his successor as commander of the western theatre of the war. Sherman's siege and capture of Atlanta, Georgia (see Atlanta Campaign) and the subsequent March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah in the autumn of 1864 sealed Sherman's position as one of the leading Union generals of the Civil War. Convinced that the Confederacy's ability to wage further war had to be definitively crushed if the fighting was to end (and that, therefore, the North had to approach the ongoing conflict as a war of conquest), Sherman's advance through Georgia and the Carolinas was accompanied by looting, brutality, and widespread destruction of civilian supplies and infrastructure. The targetting of civilians and reports of war crimes on the march have made Sherman a controversial figure, particularly in the American South, to this day. The south calls him a controversial figure for ransacking their homes, while the slaves call him a liberator for freeing them from slavery.

After the Civil War

When Grant became President of the United States in 1869, Sherman became the top general in the U.S. Army and served in that post until his retirement. As such, he commanded various campaigns against the Native American ("Indian") tribes. As in his Civil War service, in these campaigns Sherman sought not only to defeat the enemy's soldiers, but also to destroy the resources that allowed the enemy to sustain its warfare. Despite his harsh treatment of the warring Indian tribes, Sherman spoke out against government agents who treated the natives unfairly within the reservations.

In 1875 Sherman published his two-volume memoirs, a minor classic, marked by a forceful, lucid style, and the strong opinions for which Sherman has become famous. Sherman retired from the army in 1884, and lived most of the rest of his life in New York City. He was devoted to the theatre and was much in demand as a colorful speaker at dinners and banquets. He was proposed by some Democrats as a possible presidential candidate for the election of 1884. He declined as emphatically as possible, saying, "If nominated I will not run; if elected I will not serve." Such a categorical rejection of a candidacy is now referred to as a "Sherman Statement."

Death

Sherman died in New York City, where he is memorialized by an equestrian statue created by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and located the southeast entrance to Central Park. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

General Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate officer who had commanded the resistance to Sherman's troops as they marched through Georgia and South Carolina, served as a pallbearer at Sherman's funeral. It was a bitterly cold day in February, and a friend of Johnston, fearing that the general might become ill, asked him to put on his hat. Johnston famously replied: "If I were in [Sherman's] place, and he were standing in mine, he would not put on his hat."

Johnston did catch a serious cold, and died soon afterwards.

Notes

- Sherman, William Tecumseh, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman 2nd ed. (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1913 (1875), Vol. 1, 125-129.

- Sherman, William Tecumseh, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman 2nd ed. (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1913 (1875), Vol. 1, 131-134, 166.

- Quoted in Royster, Charles, The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991), 133-4.

External links

- U.S. Army Center of Military History (http://www.army.mil/cmh-pg/books/cg&csa/Sherman-WT.htm)

- William T. Sherman Family papers from the University of Notre Dame (http://www.archives.nd.edu/findaids/ead/html/SHR.htm)

- General William Tecumseh Sherman (http://ngeorgia.com/people/shermanwt.html) from About North Georgia (http://ngeorgia.com/) concentrates on Sherman's time in Georgia

| Preceded by: Ulysses S. Grant | Commanding General of the United States Army 1869–1883 | Succeeded by: Philip H. Sheridan |

| Preceded by: John Aaron Rawlins | United States Secretary of War 1869 | Succeeded by: William W. Belknap Template:End boxde:William T. Sherman fr:William Tecumseh Sherman |