Waiting for Godot

|

|

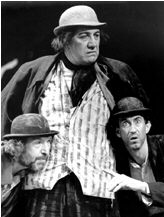

Beckett's_Tramps.jpg

Waiting for Godot is an absurdist play by Samuel Beckett, written in the late 1940s and first published in 1952. Beckett originally wrote Godot in French, his second language, as En attendant Godot (literally: While Waiting for Godot). The simplicity of the dialogue reflects this French origin. An English translation by Beckett himself was published in 1955.

| Contents |

Synopsis

The play is in two acts. The plot concerns Vladimir (also called Didi) and Estragon (also called Gogo), who arrive at a pre-specified roadside location in order to await the arrival of Godot. Vladimir and Estragon appear to be tramps: their clothes are ragged and do not fit. They pass the time in conversation. Estragon complains of his ill-fitting boots, and Vladimir struts about stiff-legged due to a painful bladder condition. They make vague allusions to the nature of their circumstances and to the reasons for meeting Godot, but the audience never learns who Godot is or why he is important. They are soon interrupted by the arrival of Pozzo, a cruel but lyrically gifted man who claims to own the land they stand on, and his servant Lucky, whom he appears to control by means of a lengthy rope. Pozzo sits down to feast on chicken, and afterwards throws the bones to the two tramps. He entertains them by directing Lucky to perform a lively dance, and then deliver an ex tempore lecture on the theories of Bishop Berkeley. After Pozzo and Lucky depart, a boy arrives with a message he says is from Godot that he will not be coming today, but will come tomorrow. The second act follows a similar pattern to the first, but when Pozzo and Lucky arrive, Pozzo has inexplicably gone blind and Lucky has gone mute. Again the boy arrives and announces that Godot will not appear, also confessing that Godot beats him and makes him sleep in a barn. The much quoted ending of the play might be said to sum up the stasis of the whole work:

- Vladimir: Well, shall we go?

- Estragon: Yes, let's go.

- They do not move.

Interpretations

The_Tramps_from_Godot.jpg

Beckett uses the characters' interaction to symbolise the tedium and meaninglessness of modern life, both major themes of the existentialists. Critic Vivian Mercier summed up the two act play with the words "nothing happens, twice." Another critic used a line from the play to sum up his review: "Nothing happens, nobody comes, nobody goes, it's awful!" This critic is referring to the work's drawn out scenes and scarcity of characters.

Despite its essential bleakness, however, it has many moments of comedy, some of it recalling the deadpan slapstick of Charlie Chaplin and Beckett's idol Buster Keaton. Some of the business involving hats was adopted from a routine done by the Marx Brothers, and it may be noted that the character schema - four characters, one of whom is mute, and one of whom bears an Italian name - may have been derived from the same source. Critic Kenneth Burke argued that the interaction of Vladimir and Estragon is based on that of Laurel and Hardy. Near the end of the play, to give one example of the play's sillier moments, Estragon removes the cord holding his trousers up so he can hang himself with it, and his trousers fall down. In the original French production Beckett was adamant that the actor playing Estragon, who was reluctant to perform so foolish a piece of business, follow the directions to the letter.

Many readers of this play have understood the character "Godot" as a symbolic representation of God. They see Godot's persistent failure to appear and Vladimir and Estragon's aimless waiting as representations of the masses hoping for a being who will never appear. This is a common interpretation of the play, but one that Beckett himself vehemently denied all his life, saying "Christianity is a mythology with which I am perfectly familiar, and so I use it. But not in this case!"

This was Beckett's third attempt at drama after an abortive attempt at a play about Samuel Johnson, and the considerably more conventional Eleutheria (which Beckett suppressed after writing Godot). Godot was the first to be performed. It was a big step back towards normal human experience after his novel The Unnamable. Subtitled "a tragicomedy," the script has little indication of setting or costume (but for Beckett's note that all four of the major characters wear bowler hats); the only indication for decor is the typically succinct "A country road. A tree. Evening" prior to Act I. As such, Godot is capable of sustaining a wide range of interpretation, including who, or what, Godot is.

While the name "Godot" is commonly pronounced with an emphasis on the second syllable (i.e. "guh-DOH"), this is in fact incorrect. According to Beckett, the emphasis is on the first syllable (i.e. "GOD-oh"). The incorrect pronunciation is apparently (also according to Beckett) North American in origin.

Skilled comedians, like Robin Williams and Steve Martin in one production (also Bert Lahr in the 1950s), have had the most success with the characters in popular esteem, and there is a heartfeltness about the dialogue and situation that is not always completely aligned with despair, along with dream-like, poetic passages; perhaps this is why the play is loved by its fans.

Beckett went on to resume his march towards the void in his new medium, and his later plays have had much less popular success, though they continue to be produced, and are generally accepted as important works.

Directly related works (other authors)

Waiting_godot.JPG

The title character of Balzac's 1851 play Mercadet is waiting for financial salvation from his never seen business partner, Godeau. Although Beckett was familiar with Balzac's prose, he only learned of this play after finishing Waiting for Godot. Ironically, Balzac's play was closely adapted to film as The Lovable Cheat (with Buster Keaton, whom Beckett greatly admired) at about the same time Beckett was writing his own play.

(Similarly, Beckett only learned of the champion Parisian cyclist Roger Godeau, whose fans reportedly "waited for Godeau", after finishing his play.)

Clifford Odets' famous 1935 play Waiting for Lefty was about workers oppressed by capitalism, waiting for the salvation in the form of union organizer Lefty. But the play ends as the workers learn that Lefty will not come after all (having been murdered).

An unauthorized prequel, of sorts, formed part II of Ian McDonald's novel King of Morning, Queen of Day (partly written in Joycean style). Two main characters are clearly meant to be the original Vladimir and Estragon.

An unauthorized sequel was written by Miodrag Bulatović in 1966: Godo je došao (Godot has come). It was translated from the Serbo-Croatian into German (Godot ist gekommen) and French. Although Beckett was noted for disallowing productions that took even slight liberties with his plays, he let this pass without incident.

Another unauthorized sequel was written by Daniel Curzon in the late nineties: Godot Arrives.

A radical transformation was written by Bernard Pautrat, performed at Théâtre National de Strasbourg in 1979-1980: Ils allaient obscurs sous la nuit solitaire (d'après En attendant Godot de Samuel Beckett). The dialog consisted of excerpts from Godot, rearranged among ten actors (Vladimir, Estragon, Pozzo, Lucky and six others).

Quotations

Estragon: Let's go.

Vladimir: We can't.

Estragon: Why not?

Vladimir: We're waiting for Godot.

Estragon: (despairingly). Ah!

Pozzo: (suddenly furious) Have you not done tormenting me with your accursed time! It's abominable! When! When! One day, is that not enough for you, one day he went dumb, one day I went blind, one day we'll go deaf, one day we were born, one day we shall die, the same day, the same second, is that not enough for you? (Calmer) They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it's night once more.

Vladimir: Was I sleeping, while the others suffered? Am I sleeping now? Tomorrow, when I wake, or think I do, what shall I say of today? That with Estragon my friend, at this place, until the fall of night, I waited for Godot? That Pozzo passed, with his carrier, and that he spoke to us? Probably. But in all that what truth will there be? (Estragon, having struggled with his boots in vain, is dozing off again. Vladimir looks at him) He'll know nothing. He'll tell me about the blows he received and I'll give him a carrot. (Pause) Astride of a grave and a difficult birth. Down in the hole, lingeringly, the grave digger puts on the forceps. We have time to grow old. The air is full of our cries. (He listens) But habit is a great deadener. (He looks again at Estragon) At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, He is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on. (Pause) I can't go on! (Pause) What have I said?

External links

- Text of the play (http://samuel-beckett.net/Waiting_for_Godot_Part1.html)

- Wam, bam! Thank you Sam! A huge resource on various interpretations of the play and its characters (http://www.samuel-beckett.net/Penelope/Godot_intro.html)

de:Warten auf Godotzh-cn:等待戈多 fr:En attendant Godottr:Godot'yu Beklerken Template:Beckett