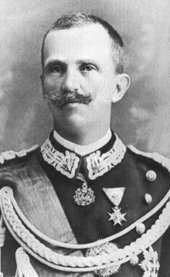

Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

|

|

| Template:House of Savoy |

Victor Emmanuel III (Italian: Vittorio Emanuele III) (November 11, 1869 – December 28, 1947), nicknamed "The soldier king", was the King of Italy (July 29, 1900 – May 9, 1946), and claimed the titles Emperor of Ethiopia (1936 - 1943) and King of Albania (1939 - 1943). He was also mockingly nicknamed sciaboletta, or "little saber", allegedly because his short stature required his uniform to be equipped with a saber shorter than the ordinary.

Victor Emmanuel III's position as Emperor of Ethiopia was not universally accepted, as Italy had overthrown the native Emperor, Haile Selassie. The United Kingdom, among many others, refused to recognise Victor Emmanuel's 'new' title (as indeed did many to his claim to be King of Albania) with King George VI as King of the United Kingdom on the advice of the British government accrediting ambassadors to Victor Emmanuel as merely 'King of Italy'. (In contrast in his role as King of Ireland, and on the advice of the Irish Government, King George accredited Irish Ambassadors to Victor Emmanuel as both king of Italy and Emperor of Ethiopia.) King Victor Emmanuel III renounced his titles of Emperor of Ethiopia and King of Albania in 1943.

| Contents |

The Royal Family

Victor Emmanuel was the only child of Umberto I of Italy and Margherita Teresa Giovanna, Princess of Savoy. In 1896 he married Elena Petrovich (1873-1953), daughter of King Nicholas I of Montenegro (who was dethroned after World War I) and had children including:

- Yolanda Margherita Milena Elisabetta Romana Maria (1901-1986), married Giorgio Carlo Calvi, Count of Bergolo (1887-1977);

- Mafalda Maria Elisabetta Anna Romana (1902-1944), married Philip of Hesse-Kassel - she died in Buchenwald, a Nazi concentration camp;

- Crown Prince Umberto (1904-1983) who married (and later following the declaration of the Republic, separated from) Princess Marie José of Belgium

- Giovanna Elisabetta Antonia Romana Maria (1907-2000), married Boris III of Bulgaria

- Maria Francesca Anna Romana (1914-2001), married Prince Luigi of Bourbon-Parma (1899-1967)

Achievements and Failures

Victor Emmanuel III remains undoubtedly Italy's most controversial monarch. His early reign showed evidence that, at least by the standards of the Savoyard monarchy, he was a man committed to a form of democracy. Yet in his decision in 1922 to appoint Benito Mussolini prime minister (having refused formal government advice to ban a fascist march on Rome, an act which provoked that government of Luigi Facta's resignation), and in particular his failure, in the face of mounting evidence, to act against Mussolini's regime's abuses of power (including as early as the 1920s, the notorious murder of Giacomo Matteotti and other opposition MPs), he lost the Italian throne the little popularity it had earned earlier in his reign.

Defenders of Victor Emmanuel have suggested that his decision not to oppose Mussolini's rise to power was based on the consideration of the economical damages caused by the constant collapsing of earlier governments, Mussolini offering a stability that the Italian Kingdom craved. The King himself suggested that his armed forces could not have defended Rome against the fascist march on the city, though then military leaders and surviving military records challenge His Majesty's claim. Mussolini's camicie nere (black shirts) were around Rome, waiting for instructions, while the Duce had already entered it and was in a hotel in via Boncompagni, making the acquaintance of Roberto Rossellini's father. The commander in chief of the defence of the Capital town, was finally ordered - it is said, directly by the king - to remove the blocks and let them pass.

Critics argued that Victor Emmanuel's decisions showed constant poor judgment and undemocratic sentiments. What is not in doubt, however, is that fascism offered a political stability that appealed to a broad mass of Italian life, not least the Roman Catholic Church which as part of its inter-war policy of negotiating concordats with states negotiated with Mussolini's government, producing the Lateran Treaty which regularised the relationship between the papacy (which had before 1870 controlled Rome) and the Kingdom of Italy. In many ways the events of the 1920s to 1940s showed each side, the monarchy, the church, the political elite and the voters, for different reasons, felt Mussolini and his regime offered a regime that, after years of political instability and infighting, seemed more appealing than what they perceived as the alternative.

Some Italians view King Victor Emmanuel as a puppet ruler because he largely bowed to Mussolini's decrees (for example he only learned of Mussolini's plans to invade Greece after the fact, and approved of them tacitly).

Yet the Italian monarchy could still have survived. Foreigners noted how even in the early 1940s newsreel images of King Victor Emmanuel and Queen Elena, when shown in cinemas, provoked applause, sometimes cheering, in contrast to the hostile silence shown toward fascist leaders. Two of Victor Emmanuel's decisions, however, arguably proved fatal to the monarchy. His decision to flee Rome in 1943, though perhaps correct from the point of view of his own safety, shocked many. It also shocked many foreign observers, who compared with the behaviour of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, who refused to leave London during the Blitz, or Pope Pius XII, who mixed with Rome's crowds and prayed with them after the popular Roman quartiere of San Lorenzo was bombed and destroyed. His silence in 1938, when Fascism issued its racial laws, was astonishing for the tolerant Italian people, and this lack of protection of part of the nation soon created a moral barrier between the Crown and the nation. Many Jewish officers committed suicide, so to die in the uniform before being dismissed, and this caused the army to lose the special loyalty to the Quirinale.

If the monarchy was to have any future, Victor Emmanuel III arguably could have no part of it. And with a popular Crown Prince and Princess much less tainted by fascism than the monarch, it could have survived. Some say that it was a fatal mistake to remain on the throne, instead of abdicating and allowing a new chapter in the history of the monarchy to begin. Others instead suggest that in 1943 the situation could not allow an abdication, because the immediate consequence would have been the lack of political personality of the whole monarchy, in a moment of confusion, at the beginning of a civil war, with foreign armies on the territory.

If the history of monarchy in Europe from the 1940s was made up of strong images like those of King George and Queen Elizabeth in the 1940s, Michael of Romania's role in overthrowing his own country's fascism, or Spain's King Juan Carlos's defence of democracy in face of a threatened coup d'etat in the 1980s, Victor Emmanuel showed no such leadership skills. His abdication on the eve of the referendum on the future of the monarchy at best achieved little, being too little far too late. At worst, it simply reminded undecided voters of the role of the monarchy and of he himself in the fascist period, at a time when monarchists hoped voters would have been focusing on the positive impressions made by Crown Prince Umberto and Princess Maria José as the effective monarchs of Italy since 1943. By what are perceived by some historians as mis-timed actions (appointing Mussolini, fleeing Rome) and mis-timed inactions (failure to support his government's plan to suppress the 1922 March on Rome, his failure to abdicate in 1943), Victor Emmanuel III weighed down the Italian monarchy with his mistakes, a weight which the 'May' king and queen, King Umberto II and Queen Maria José were unable to shift in their short but impressive month-long reign. Victor Emmanuel went to exile to Egypt and died there in 1947. Others instead do underline that also the pragmatical tradition of the House of Savoy, of taking a decision only when unavoidable, a sort of political irresolution, was one of the reasons for their defeat. The birth of the Italian Republic is more evident indeed than the defeat of Italian monarchy, and was justified by many reasons, also because at a certain time the Church stopped supporting the Royal House (which Vatican always considered as an invasor) and left them alone.

Related articles

External links

- External link: Genealogy of recent members of the House of Savoy (http://www.chivalricorders.org/royalty/gotha/italygen.htm)

Additional reading

- Denis Mack Smith, Italy and Its Monarchy (Yale University Press, 1989) (ISBN 0300051328)

| Preceded by: Umberto I | King of Italy 1900-1946 | Succeeded by: Umberto II |

| Preceded by: Haile Selassie | Emperor of Ethiopia 1936-1941 | Succeeded by: Haile Selassie |

| Preceded by: Zog I | King of Albania 1939-1943 | Succeeded by: — Template:End boxde:Viktor Emanuel III. et:Vittorio Emanuele III fr:Victor-Emmanuel III d'Italie it:Vittorio Emanuele III di Savoia nl:Victor Emanuel III van Italië ja:ヴィットーリオ・エマヌエーレ3世 simple:Vittorio Emanuele III fi:Viktor Emanuel III sv:Viktor Emanuel III av Italien |