Church of Scotland

|

|

The Church of Scotland (commonly known as the Kirk) is the national church of Scotland. It is a Presbyterian Church, decisively shaped by the Scottish Reformation.

Cofs_logo.jpg

| Contents |

Position in Scottish Society

The Church of Scotland has around 1,400 active ministers, 1,200 congregations, and its membership at approximately 600,000 comprises about 12% of the population of Scotland. However, in the 2004 national census, 42% of Scots identified themselves as ‘Church of Scotland’ by religion.

Although it is the national church, the Kirk is not a "state church", and in this, and other, regards is dissimilar to the Church of England (the established church in England). Under its constitution, which is recognised by acts of Parliament, the Kirk enjoys complete independence from the state in spiritual matters. It is thus both established and free.

The British monarch (when in Scotland) is simply a member of the Kirk (she is not, as in England, its "Supreme Governor"). The monarch’s coronation oath includes a promise to defend the security of the Church of Scotland. She is formally represented at the annual General Assembly by a Lord High Commissioner (unless she chooses to attend in person). The role is purely formal.

The Kirk is committed to its ‘distinctive call and duty to bring the ordinances of religion to the people in every parish of Scotland through a territorial ministry’. (Article 3 of its ‘Articles Declaratory’). In practice this means that the Kirk maintains a presence in every community in Scotland – and exists to serve not only its members but all Scots (the majority of funerals in Scotland are taken by its ministers). It also means that the Kirk redistributes resources from wealthy congregations to ensure its continued presence in other parts of Scotland.

The Kirk played a leading role in the provision of universal education in Scotland, largely due to its desire that all people should be able to read the Scripture. However, today it does not operate schools - these having been entrusted into the care of the state in the later half of the 19th century.

The Church of Scotland’s ‘Board of Social Responsibility’ is the largest provider of social care in Scotland today, running projects for various disadvantages and vulnerable groups including care for the elderly, help with alcoholism, drug and mental health problems and assistance for the homeless.

The Kirk has never shied from involvement in Scottish politics. It was (and is) a firm opponent of nuclear weaponry. Supporting devolution, it was one of the parties involved in the Scottish Constitutional Convention, which resulted in the setting up of the Scottish parliament in 1997. Indeed, from 1997-2004 the Parliament met int the Kirk's Assembly Halls in Edinburgh, whilst its own building was being constructed.

Constitution

Church-scot-standard.PNG

Standard of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland is Presbyterian in polity, and Reformed in theology. The most recent articulation of its legal position (the ‘Articles Declaratory’ of 1921) spells out the key concepts.

Its basis of faith is the Word of God, which it views as being ‘contained in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament’. Its principle subordinate standard is ‘’the Westminster Confession of Faith’’ (1647), although here liberty of opinion is granted on those matters ‘which do not enter into the substance of the faith’ (Art. 2 and 5).

As a Presbyterian church, the Kirk has no bishops, but is rather governed by elders and ministers (collectively called presbyters) sitting in a series of courts. Each congregation is led by a Kirk Session. The Kirk Sessions in turn are answerable to regional presbyteries (the Kirk currently has over 40). The supreme body is the annual General Assembly, which meets each May in Edinburgh.

The chairperson of each court is known as the ‘moderator’ – at the local level of the Kirk Session, the moderator is normally the parish minister; Presbyteries and the General Assembly elect a moderator each year. The Moderator of the General Assembly serves for the year as the public representative of the Church – but beyond that enjoys no special powers or privileges and is in no sense the ‘leader’ or official ‘spokesperson’ of the Kirk.

History

see further History of Scotland

The Kirk traces its roots back to the beginnings of Christianity in Scotland, but its identity is principally shaped by the Scottish Reformation of 1560. At that point, the church in Scotland broke with Rome and adopted Presbyterianism, in a process of protestant reform led, among others, by John Knox. It reformed its doctrines and government on the Presbyterian principles of John Calvin which Knox had been exposed to while living in Switzerland. In 1560, the Scottish Parliament adopted Presbyterianism as the form for Scotland and set up a structure to implement it. However while Parliament was supportive of Presbyterianism, subsequent monarchs were not. Over the next hundred or more, years bishops were imposed on the Kirk from time to time. In 1638 a National Covenant was signed by large numbers of Scots in protest at this. These people, the Covenanters, were persecuted as a result.

The modern situation largely dates from 1690, when as part of the Glorious Revolution, the reformed, established, Presbyterian nature of the Kirk was guaranteed. However, controversy still surrounded the relationship between the Church’s independence and the civil law of Scotland. The interference of civil courts with Church decisions, particularly over the right to appoint ministers, led to a number of groups succeeding from the Kirk. This began with the secession of 1747 and culminating in the Disruption of 1843, when a large portion of the Church broke away to form the Free Church of Scotland. The succeeding groups tended to divide and reunite among themselves – leading to a proliferation of Presbyterian denominations in Scotland. However, in the 1920s, the United Kingdom Parliament passed the Church of Scotland Act 1921, finally recognising the full independence of the Church, and as a result of this the Kirk was reunited with the United Free Church. However, many Presbyterians denominations still remain outside of the Kirk.

Worship and Doctrine

Unlike the Church of England, the Kirk has no compulsory prayer book although it does have a hymn book (the 4th edition was published in 2005) and its Book of Common Order contains recommendations for public worship. Preaching is the central focus of most Kirk services. Traditionally, Scots worship centred on the singing of metrical psalms and paraphrases, but for generations these have been supplemented with Christian music of all types. The Kirk today cannot be said to have any uniformed style of worship. Worship is the responsibility of the minister in each parish, although increasingly the church is encouraging others to participate in services.

In common with other protestant denominations, the church recognises two sacraments: Baptism and Holy Communion (the Lord’s Supper). The Kirk baptises both believing adults and the children of Christian families. Communion in the Kirk today is open to Christians of whatever denomination, without precondition. Communion services are usually taken fairly seriously in the Kirk; traditionally, a congregation held only three or four per year, although practice now greatly varies between congregations.

Theologically, the Kirk is a ‘broad church’, including those who would term themselves ‘evangelical’, ‘conservative’ and ‘liberal’ in their beliefs and interpretation of Scripture.

The Kirk is a member of ACTS (‘Action of Churches Together in Scotland’) and, through, its Board of Ecumenical Relations, works closely with other denominations in Scotland. The present inter-denominational cooperation marks a distinct change from attitudes in certain quarters of the Kirk in the early twentieth century and before, when opposition to Irish Roman Catholic immigration was vocal.

Reform

The Church of Scotland today faces many grave difficulties. Since the 1950’s its membership has continued to fall – now being around half what it was then. It faces problems of finance and the upkeep of a legacy of ancient church buildings. Until recently it also faced a shortage of ministry candidates – but recruitment is now significantly higher.

One of the tenets of the Kirk, since the reformation, has been its notion of being an ‘’ecclesia reformata semper reformanda’’ – a church, which is reformed, but always in the process of reforming. Recently, the Kirk produced its ‘Church without Walls’ report (2001) which embodies an ethos of change, and a focus on the grassroots life of the Church rather than its necessary institutions.

Like most western denominations, the membership of the Kirk is also aging, and it has struggled to maintain its relevance to the younger generations. The Kirk has made attempts to address there problems, at both a congregational and national level. The annual youth assembly and the presence of youth delegates at the General Assembly have served as a visible reminder of the Kirk’s commitment.

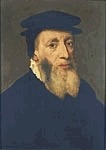

Since as early as 1968, all ministries and offices in the church have been open to women on an equal basis. However, it was not until 2004 that a woman was chosen to be Moderator of the General Assembly. Dr. Alison Elliot was also the first elder to be chosen since George Buchanan, four centuries before.

See also

External links

- Official Church of Scotland website (http://www.churchofscotland.org.uk)

- 'Church without Walls' report (http://www.churchwithoutwalls.org.uk/)

- website of Action of Churches Together in Scotland (http://www.acts-scotland.org)de:Church of Scotland