United States Bill of Rights

|

|

The Bill of Rights is the name given to the first ten amendments of the United States Constitution. When the Constitution was submitted to the state legislatures for ratification, many of its opponents claimed that the reason the Constitution did not include a bill of rights was because the document was an aristocratic scheme to remove the rights of Americans. Supporters, known as Federalists, assured Americans that a Bill of Rights would be added by the First Congress.

| Contents |

|

1.1 Controversy |

Origin

After the Constitution was ratified, the first U.S. Congress met in Federal Hall in New York City. Most of the delegates agreed that a bill of rights was needed and most of them agreed on the rights they believed should be enumerated.

Controversy

The idea of adding a bill of rights to the Constitution was originally controversial. The argument was that the Constitution, as written, did not explicitly enumerate or guarantee the rights of the people, and as such needed an addition to ensure such protection. However, many Americans at the time were opposed to the idea of a bill of rights: If such a bill were created, they feared that it would eventually come to be interpreted as a list of the only rights Americans had. In other words, the list of rights would be the only rights one had, and if interpreted narrowly, the existence of such a bill of rights could effectively be used to constrain the liberty of the American people instead of ensuring it. For example, Alexander Hamilton opposed any such bill of rights, writing:

It has been several times truly remarked, that bills of rights are in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgments of prerogative in favor of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. Such was Magna Charta, obtained by the Barons, sword in hand, from king John....It is evident, therefore, that according to their primitive signification, they have no application to constitutions professedly founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate representatives and servants. Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing, and as they retain every thing, they have no need of particular reservations. "We the people of the United States, to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the United States of America." Here is a better recognition of popular rights than volumes of those aphorisms which make the principal figure in several of our state bills of rights, and which would sound much better in a treatise of ethics than in a constitution of government....

I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and in the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers which are not granted; and on this very account, would afford a colourable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why for instance, should it be said, that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretence for claiming that power. (Alexander Hamilton, Federalist, no. 84, 575-581, 28 May 1788)

Supporters of a bill of rights argued that such a list of rights should not and would not be interpreted as being exhaustive; In other words, the rights to be enumerated would be some of the most important rights that people had, but many other rights existed as well. People in this school of thought were confident that the judiciary would interpret these rights in an expansive fashion.

Drafting the Bill of Rights

The task of drafting the Bill of Rights fell to James Madison, who based his work on George Mason's earlier work, the Virginia Declaration of Rights. It had been decided earlier that the Bill of Rights would be added to the Constitution in the form of amendments (the list of rights was not inserted into the text of the Constitution because it was feared that modifying the document's text would necessitate the rather painful process of re-ratifying the Constitution).

The Bill of Rights includes rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press, free excercise of religion, and freedom of assembly. It also includes a clause mandating that the Bill of Rights must not be interpreted as a comprehensive list of all rights had by Americans, but rather a list of just some of the most important rights.

Twelve amendments were originally proposed in 1789, but two failed to be ratified by the states at the same time as the remaining ten. These two amendments, originally numbered first and second, were drafted and submitted as:

Article the first ... After the first enumeration required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred; after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor more than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons.

Article the second ... No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.

Several important public officials, including James Madison and United States Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, retained the confusing practice of referring to each of the ten amendments in the Bill of Rights by the enumeration found in the first draft.

Passing the Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights was easily passed by the House in 1789. When it was sent to the Senate, an amendment was removed that forbade states from interfering with the rights of the people. Since records of the meetings of the Senate are not available to the public, no one can say for sure why this amendment was removed (later, in 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment would be passed establishing the principle that states may not interfere with the rights guaranteed to citizens by the Constitution).

On November 20th of that same year, New Jersey became the first state in the newly-formed Union to ratify these amendments. Other states followed, and the last ten of the original twelve amendments—now designated as the First through Tenth Amendments—became law on December 15, 1791, when they were ratified by the Virginia legislature. These ten amendments quickly became known as the Bill of Rights. The second proposed amendment ("Article the second" as presented to the states) was finally ratified in 1992 as the Twenty-seventh Amendment to the Constitution; it restricts the power of Congress to raise their own pay. The first proposed amendment ("Article the first" as presented to the states) is theoretically still pending before the states, but unlikely to ever be fully ratified. That amendment would regulate the method of determining the size of the United States House of Representatives. Perhaps unaware—given the primitive nature of long-distance communications in the 1700s—that Virginia's approval six months earlier had already made ten of the package of twelve part of the Constitution, lawmakers in Kentucky ratified the entire set of twelve in June of 1792 during that commonwealth's initial month of statehood.

Incorporation theories

In the first decades of the Republic, the Bill of Rights was considered to apply only to the federal government and not to the several state governments. Thus, states had established state churches up until the 1820s, and Southern states, beginning in the 1830s, could ban abolitionist propaganda. In the case of Barron v. Baltimore, the Supreme Court specifically ruled that the Bill of Rights provided "security against the apprehended encroachments of the general government—not against those of local governments."

Two different approaches were taken to incorporating the U.S. Bill of Rights in order to make them applicable to all of the state and local governments in the Union. The first of these theories held the traditional view that the U.S. Bill of Rights were amendments to the Constitution of the United States of America, not amendments to individual state constitutions. To overcome the problems created by this interpretation, a theory called gradual incorporation was adopted by some justices. By offering opinions upon specific cases, they could bind the states to the reasoning behind the amendments, although they could not bind them to the amendments themselves. It was a complicated process, and the wedge they selected was the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

In 1925 with Gitlow v. New York, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment (which had been adopted in 1868) made certain applications of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states. The Supreme Court then used the Gitlow case as precedent for a series of decisions that made most of the provisions of the first eight amendments applicable to the states under a theory of gradual incorporation.

The second theory was that of total and direct incorporation, and its author was Justice Hugo Black. He chose the 1949 case of Adamson v. California to make his point in a massive dissenting Opinion that runs to the length of a small book. He narrowly missed in his attempt. It was in that case that Hugo Black began to constantly state in many following cases that the U.S. Bill of Rights owes its origin to the legal fight of Freeborn John Lilburne in the 1600s. In 1966 Hugo Black succeeded in getting William O. Douglas to join with him in Miranda v. Arizona, for which Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the majority Opinion. The foundation of that case is the right to remain silent, and the words of John Lilburne in his 1637 Star Chamber trial are quoted directly in the majority Opinion.

Twenty-seventh Amendment

It remains controversial whether the Twenty-seventh Amendment should be considered a part of the Bill of Rights; it is listed below only for convenience.

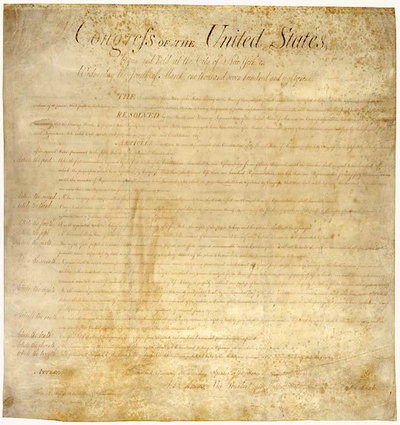

The original copy of the Bill of Rights, which contains the text of all twelve proposed amendments, can be seen by the public today at the National Archives in Washington, DC.

The amendments

The amendments making up the Bill of Rights are:

- Amendment I – Freedom of speech, press, religion, peaceable assembly, and to petition the government. [1] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#1)

- Amendment II – Right to keep and bear arms. [2] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#2)

- Amendment III – Protection from quartering of troops. [3] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#3)

- Amendment IV – Protection from unreasonable search and seizure. [4] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#4)

- Amendment V – Due process, double jeopardy, self-incrimination, private property. [5] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#5)

- Amendment VI – Trial by jury and other rights of the accused. [6] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#6)

- Amendment VII – Civil trial by jury. [7] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#7)

- Amendment VIII – Prohibition of excessive bail, as well as cruel or unusual punishment. [8] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#8)

- Amendment IX – The Bill of Rights does not take away any right already held by the people under the constitution. [9] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#9)

- Amendment X – Grants residual power to the states and to the people. [10] (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/amendments_1-10.html#10)

- Amendment XXVII – Congress cannot increase its members' pay until the next House election. [11] (http://www.archives.gov/national_archives_experience/charters/constitution_amendments_11-27.html#27)

Transcription

The following text is a transcription of the first 10 amendments to the Constitution in their original form. These amendments were ratified December 15, 1791, and form what is known as the "Bill of Rights." Also included is the Twenty-seventh amendment, which was ratified on May 5, 1992.

Preamble

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES

Begun and held at the City of New York, on Wednesday, the Fourth of March, One Thousand Seven Hundred Eighty-nine.

The Conventions of a number of the States having, at the Time of their Adopting the Constitution, expressed a Desire, in Order to prevent Misconstruction or Abuse of its Powers, that further declaratory and restrictive Clauses should be added: And as exceeding the Ground of public Confidence in the Government will best insure the beneficent Ends of its Institution,

RESOLVED, by the Senate, and House of Representatives, of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, Two Thirds of both Houses concurring, That the following Articles be proposed to the Legislatures of the several States, as Amendments to the Constitution of the United States: All, or any of, which Articles, when ratified by Three-Fourths of the said Legislatures, to be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as part of the said Constitution, viz.

Articles in Addition to, and Amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America, proposed by Congress, and ratified by the Legislatures of the several States, pursuant to the Fifth Article of the original Constitution.

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

Amendment VII

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Amendment XXVII

No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of representatives shall have intervened.

Note: Amendment XXVII is actually before Amendment I in the original document, but was not ratified until 1992.

Reference

- Source for 14th amendment sentences: Spaeth, Harold J.; and Smith, Edward Conrad; HarperCollins College Outline: The Constitution of the United States; 13 ed.; ISBN 0064671054

See also

- The British Bill of Rights of 1689 on which it was partly based.

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen — adopted by France at the same time as the US Bill of Rights.

External links

- The full text of the United States constitutional amendments (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/charters_of_freedom/bill_of_rights/bill_of_rights.html)

- Teaching the Bill of Rights (http://www.ericdigests.org/pre-929/rights.htm)

- Alexander Hamilton, Federalist, no. 84, 575--81 (http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/bill_of_rightss7.html) The Federalist Papers, on opposition to the Bill of Rights

- Thirty-Thousand.org (http://www.thirty-thousand.org/pages/article1_history.htm) Site advocating an increase in the size of the House of Representatives

- Krusch, Barry (2003). Would The Real First Amendment Please Stand Up? (http://www.krusch.com/real/real2.html) Online book arguing that the Supreme Court's interpretation of the First Amendment has created a 搗irtual First Amendment" that is radically different from the true amendment

- The Second Amendment and Commas (http://www.freerepublic.com/forum/a39388c210c1b.htm) Arguing that differences in punctuation have been used to misconstrue the Second Amendment

et:Bill of Rights (1791) nl:Bill of Rights de:Bill of Rights (USA) he:מגילת הזכויות (ארצות הברית) zh:权利法案 (美国)