Tuskegee Syphilis Study

|

|

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972) was a clinical study, conducted around Tuskegee, Alabama, where 400 poor, mostly illiterate African American sharecroppers became part of a study on the treatment and natural history of syphilis without due care to its subjects. This notorious study led to major changes in how patients are protected in clinical studies. Individuals enrolled in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study did not give informed consent and were not informed of their diagnosis; instead they were told they had "bad blood" and could receive free treatment.

Critically, by 1947 penicillin had become standard treatment for syphilis. Prior to this discovery syphilis frequently led to a chronic, painful and fatal multisystem disease. Rather than treat all syphilitic subjects with penicillin and close the study, the Tuskegee scientists witheld penicillin or information about penicillin purely to continue to study how the disease spreads and kills. The study continued until 1972, when a leak to the press rather than any ethical or moral consideration resulted in its termination. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study is often cited as one of the greatest ethical breaches of trust between physician and patients in the setting of a clinical study in the United States. While the medical crimes of Nazi Germany led to the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Geneva, fallout from the Tuskegee Syphilis Study led to the Belmont Report and establishment of National Human Investigation Board, and the requirement for establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs).

| Contents |

Study clinicians

Tuskegeegroup.jpg

The study group was formed as part of the venereal disease section of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS). The start of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study is most commonly attributed to Dr. Taliaferro Clark. His initial aim was to follow untreated syphilis in a group of black men for only 6-8 months and then follow up with a treatment phase. Nevertheless Dr. Clark agreed with the deceptive practices suggested by other study memebers. Clark retired the year after the beginning of the study.

Dr. Eugene Dibble was head of the John Andrew Hospital at the Tuskegee Institute.

Dr. Oliver C. Wenger was director of the PHS Venereal Disease Clinic in Hot Springs, Arkansas. He was an enthusiastic supporter of mass screening for syphilis and mass treatment programs in the Black community. At various stages of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Wenger was attached to the Macon County activities, and he played a critical role in developing early study protocols. Wenger continued to advise and assist the Tuskegee Study when it turned into a long term, no-treatment observational study, and he consistently supported a policy of concealing the aims of the study from the subjects as he feared that full disclosure would lead to their non-cooperation.

Dr. Raymond H. Vonderlehr was the on-site director of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in 1932, and he conducted many of the initial physical exams and medical procedures. Vonderlehr developed the policies that shaped the next stage of the project. For example, he decided to gain the "consent" of the subjects for spinal taps (to look for signs of neurosyphilis) by depicting the diagnostic tests as a "special free treatment." Dr. Wenger subsequently congratulated him for his "flair for framing letters to negroes." Vonderlehr retired as head of the venereal disease section in 1943.

Dr. John R. Heller, Dr. Vonderlehr's assistant, succeeded Vonderlehr as director of the venereal disease section of PHS. Heller's leadership coincided with the years when penicillin was introduced as routine treatment for syphilis in other PHS clinics, and when the Nuremberg Code to protect the rights of research subjects was formulated. Heller was alive when the study was brought to public attention in 1972, and defended the ethics of the study.

Nurse Eunice Rivers was an African American nurse who trained at Tuskegee and was recruited from the John Andrew Hospital when the study began. Dr. Vonderlehr became a strong advocate for her role. As the study became a constant fixture within the PHS, Nurse Rivers became the chief continuity person and was the only staff person to work with the study for all 40 years of its existence. By the 1950s, Nurse Rivers' had become pivotal to the study—her personal knowledge of all the subjects allowed the very long follow up to be maintained.

Study details

The study was originally started as a study on the incidence of syphilis in the Macon County population. The cohort would be studied for 6 to 8 months, then treated with contemporary treatments (including Salvarsan, mercurial ointments and bismuth) which were quite toxic and somewhat effective. The initial intentions of the study were to benefit public health in this poor population as evidenced by participation from the Tuskegee Institute, the Black university founded by Booker T. Washington. Its affiliated hospital lent the PHS its medical facilities for the study, and other predominantly black institutions as well as local black doctors also participated. The philanthropic Rosenwald Fund was to provide monies to pay for the eventual treatment. The study recruited 400 syphilitic Black men and 200 healthy Black men as controls.

The first critical turning point in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study came in 1929 when the the Wall Street Crash led the Rosenwald Fund to withdraw its funding. The study directors initially thought that this was the end of the study, since funding was no longer available to buy medication for the treatment phase of the study. A final report was issued.

In 1928, Sweden's Oslo Study had reported on the pathologic manifestations of untreated syphilis in several hundred white males. This study was a retrospective study; investigators pieced together information from patients that had already contracted syphilis and had remained untreated for some time. The Tuskegee study group decided to perform a prospective study equivalent to the Oslo Study. The study eventually became "the longest nontherapeutic experiment on human beings in medical history."

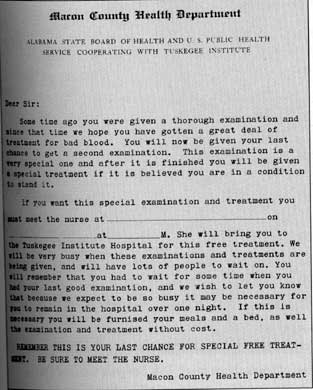

Ethical consideration, poor from the start, rapidly deteriorated. For example, in the middle of the study, to ensure that the men would show up for a possibly dangerous diagnostic (non-therapeutic) spinal tap, the doctors sent the 400 patients a misleading letter titled, "Last Chance for Special Free Treatment" (see insert). The study also required all participants to undergo an autopsy after death—participants were never informed of this requirement. For many participants, treatment was intentionally denied. Many patients were lied to and given placebo treatments—in order to "observe" the fatal progression of the disease. In 1934, the first clinical data was published, with the first major report being released in 1936.

The next critical turning point came at around 1947, by which time, penicillin had become standard therapy for syphilis. Several U.S. Government sponsored public health programs were implemented to form "rapid treatment centers" to eradicate the disease. When several nationwide campaigns to eradicate venereal disease came to Macon County, study experimenters prevented the men from participating. During World War II, 250 of the men registered for the draft and were consequently diagnosed and ordered to obtain treatment for syphilis, however then the PHS exempted them. The PHS representative at the time is quoted: "So far, we are keeping the known positive patients from getting treatment."

By the end of the study, only 74 of the test subjects were still alive. Twenty-eight of the men had died directly of syphilis, 100 were dead of related complications, 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children had been born with congenital syphilis.

Study termination and aftermath

Buxton.jpg

In 1966, Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal disease investigator in San Francisco, sent a letter to the director of the Division of Venereal Diseases to express his concerns about the morality of the experiment. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) reaffirmed the need to continue the study until completion (until all subjects had died and had been autopsied). To bolster its position, the CDC sought and gained support for the continuation of the study from the local chapters of the National Medical Association (representing African-American physicians) and the American Medical Association.

With his concerns rebuked, Peter Buxton went to the press. The story broke first in the Washington Star July 25, 1972, then became front page news in the New York Times the following day. As a result of public outcry, in 1972, an ad hoc advisory panel was appointed which determined the study was medically unjustified and ordered the termination of the study. As part of a settlement of a class action lawsuit subsequently filed by NAACP, 9 million dollars and the promise of free medical treatment was given to surviving participants and surviving family members who had been infected as a consequence of the study.

In 1974 the National Research Act became law, creating a commission to study and write regulations governing studies involving human participants.

On May 16, 1997, with five of the eight remaining survivors of the study attending the White House ceremony, President Bill Clinton formally apologized to Tuskegee study participants: "What was done cannot be undone, but we can end the silence...We can stop turning our heads away. We can look at you in the eye, and finally say, on behalf of the American people, what the United States government did was shameful and I am sorry."

Ethical implications

The early ethics of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study may be considered in isolation at study inception. In 1932, treatments for syphilis were relatively ineffective and had severe side effects. It was known that syphilis was particularly prevalent in poor, black communities. The intention of the Study was in part to measure the prevalence of the disease, to study its natural history and the real effectiveness of treatment. Prevailing medical ethics at the time did not have the exacting standards for informed consent currently expected; doctors routinely withheld information about patients' condition from them. A clinical study to try find the effectiveness of treatment of this then terrible disease was not inherently wrong. However, this study exploited a vulnerable sub-population to answer a question which would have been of benefit to the whole population. This was, some argue, a manifestation of racism on the part of the study organizers. There was no question that a literate white syphilitic would not have been given the best treatment at the time—namely (arsenic and mercury).

However, with the development of an effective, simple treatment for syphilis (i.e. penicillin), and changing ethical standards, the ethical and moral judgements became absolutely indefensible. By the time the study had closed, dozens of men had died from syphilis and many of their wives had become infected and their children born with congenital syphilis. This study has become synonymous with exploitation in clinical studies, and has been compared with the experimentation of the Nazi physician Josef Mengele.

Sociological studies have shown that the Tuskegee Syphilis Study has predisposed many African Americans to distrust medical and public health authorities. The Study is likely a significant factor in the low participation of African Americans in clinical trials and organ donation efforts and in the reluctance of many Black people to seek routine preventive care.

The aftershocks of this study led directly to the establishment of the National Human Investigation Board in the US, the establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and the Belmont Report. Special consideration must be given to ethnic minorities and vulnerable groups in the design of clinical studies.

References

- James H. Jones. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment (New York: Free Press, 1981 & 1993).

- Susan M. Reverby, ed. Tuskegee's Truths: Rethinking the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

- Jean Heller (Associated Press), "Syphilis Victims in the U.S. Study Went Untreated for 40 Years" New York Times, July 26, 1972: 1, 8.

- Thomas, Stephen B. and Quinn, Sandra Crouse, "The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932–1972: Implications for HIV Education and AIDS Risk Programs in the Black Community," American Journal of Public Health 81 (1991): 1503.

External links

- CDC Tuskegee Syphilis Study timeline (http://www.cdc.gov/nchstp/od/tuskegee/time.htm)

- CDC Tuskegee Syphilis Study Page (http://www.cdc.gov/nchstp/od/tuskegee/)

- University of Virginia: The Troubling Legacy Of The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (http://hsc.virginia.edu/hs-library/historical/apology/)

- NPR: Remembering Tuskegee: Syphilis Study Still Provokes Disbelief, Sadness (http://www.npr.org/programs/morning/features/2002/jul/tuskegee/index.html)

- Internet Resources on the Tuskeegee Study (http://www.dc.peachnet.edu/~shale/humanities/composition/assignments/experiment/tuskegee.html)

- Tuskegee Re-examined (http://www.spiked-online.com/Articles/0000000CA34A.htm) Spiked-online article laying out the case for a defense of the goals and methods of the study in its historical context (contains outdated medical assumptions and other inaccuracies)