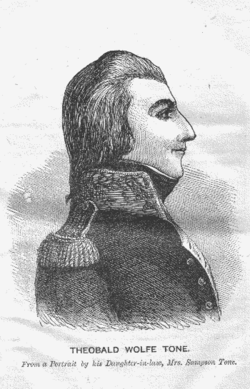

Theobald Wolfe Tone

|

|

Theobald Wolfe Tone, commonly known as Wolfe Tone (20 June 1763 - 19 November 1798) was a leading figure in the Irish independence movement.

Early Years

The son of Peter Tone, a coachmaker, he was born in Dublin. His grandfather was a small farmer in county Kildare, and his mother was the daughter of a captain in the merchant service. Following a duel in which a man was killed, Tone served as a tutor to Anthony and Robert Martin, younger brothers of Colonel Richard Martin of Dangan, Co. Galway, for some years in the early 1780s. During Martin's frequent absences, he had an affair with his wife. Though entered as a student at Trinity College, Dublin, Tone gave little attention to study, his inclination being for a military career; but after eloping with Matilda Witherington, a girl of sixteen, he took his degree in 1786, and read law in London at the Middle Temple and afterwards in Dublin, being called to the Irish bar in 1789.

Politician

Disappointed at finding no notice taken of a wild scheme for founding a military colony in the South Seas which he had submitted to William Pitt the Younger, Tone turned to Irish politics. An able pamphlet attacking the administration of the marquess of Buckingham in 1790 brought him to the notice of the Whig club; and in September 1791 he wrote a remarkable essay over the signature "A Northern Whig," of which 10,000 copies are said to have been sold. The principles of the French Revolution were at this time being eagerly embraced in Ireland, especially among the Presbyterians of Ulster, and two months before the appearance of Tone's essay a meeting had been held in Belfast, where republican toasts had been drunk with enthusiasm, and a resolution in favour of the abolition of religious disqualifications had given the first sign of political sympathy between the Roman Catholics and the Protestant dissenters of the north. The essay of " A Northern Whig " emphasized the growing breach between the Whig patriots like Henry Flood and Henry Grattan, who aimed at Catholic emancipation and parliamentary reform without disloyalty to the connection with England, and the men who desired to establish a separate Irish republic. Tone expressed contempt for the constitution which Grattan had so triumphantly extorted from the British government in 1782; and, himself a Protestant, he urged co-operation between the different religious sects in Ireland as the only means of obtaining complete redress of Irish grievances.

Society of the United Irishmen

In October 1791 Tone converted these ideas into practical policy by founding, in conjunction with Thomas Russell (1767-1803), Napper Tandy and others, the Society of the United Irishmen. The original purpose of this society was no more than the formation of a political union between Roman Catholics and Protestants, with a view to obtaining a liberal measure of parliamentary reform; it was only when it was obvious that this was unattainable by constitutional methods that the majority of the members adopted the more uncompromising opinions which Wolfe Tone held from the first, and conspired to establish an Irish republic by armed rebellion. Tone himself admitted that with him hatred of England had always been "rather an instinct than a principle", though until his views should become more generally accepted in Ireland he was prepared to work for reform as distinguished from revolution. But he wanted to root out the popular respect for the names of Charlemont and Grattan, transferring the leadership to more militant campaigners. Grattan was a reformer and a patriot without democratic ideas; Wolfe Tone was a revolutionary whose principles were drawn from the French Convention. Grattan's political philosophy was allied to that of Edmund Burke; Tone was a disciple of Georges Danton and Thomas Paine.

Democratic principles were gaining ground among the Catholics as well as among the Presbyterians. A quarrel between the moderate and the more advanced sections of the Catholic Committee led, in December 1791, to the secession of sixty-eight of the former, led by Lord Kenmare; and the direction of the committee then passed to more violent leaders, of whom the most prominent was John Keogh, a Dublin tradesman. The active participation of the Catholics in the movement of the United Irishmen was strengthened by the appointment of Tone as paid secretary of the Roman Catholic Committee in the spring of 1792. Despite his desire to emancipate his fellow countrymen, Tone had very little respect for the Catholic faith (a view shared by many subsequent Irish republicans). When the legality of the Catholic Convention in 1792 was questioned by the government, Tone drew up for the committee a statement of the case on which a favourable opinion of counsel was obtained; and a sum of £1500 with a gold medal was voted to Tone by the Convention when it dissolved itself in April 1793. Burke and Grattan were anxious that provision should be made for the education of Irish Roman Catholic priests in Ireland, to preserve them from the contagion of Jacobinism in France; Wolfe Tone, "with an incomparably juster forecast", as Lecky observes, "advocated the same measure for exactly opposite reasons". He rejoiced that the breaking up of the French schools by the revolution had rendered necessary the foundation of St Patrick's College, Maynooth, which he foresaw would draw the sympathies of the clergy into more democratic channels (he was unaware that the government was financing the college). In 1794 the United Irishmen, persuaded that their scheme of universal suffrage and equal electoral districts was not likely to be accepted by any party in the Irish parliament, began to found their hopes on a French invasion. An English clergyman named William Jackson, a man of infamous notoriety who had long lived in France, where he had imbibed revolutionary opinions, came to Ireland to negotiate between the French committee of public safety and the United Irishmen. For this emissary Tone drew up a memorandum on the state of Ireland, which he described as ripe for revolution; the paper was betrayed to the government by an attorney named Cockayne to whom Jackson had imprudently disclosed his mission; and in April 1794 Jackson was arrested on a charge of treason.

Irish_Stamp_Wolfe_Tone.jpg

Wolfe Tone

Several of the leading United Irishmen, including Reynolds and Hamilton Rowan, immediately fled the country; the papers of the United Irishmen were seized, and for a time the organisation was broken up. Tone, who had not attended meetings of the society since May 1793, remained in Ireland till after the trial and suicide of Jackson in April 1795. Having friends among the government party, including members of the Beresford family, he was able to make terms with the government, and in return for information as to what had passed between Jackson, Rowan and himself he was permitted to emigrate to the United States of America, where he arrived in May 1795. Living at Philadelphia, he wrote a few months later to Thomas Russell expressing unqualified dislike of the American people, whom he was disappointed to find no more truly democratic in sentiment and no less attached to authority than the English; he described George Washington as a "high-flying aristocrat", and he found the aristocracy of money in America still less to his liking than the European aristocracy of birth.

Tone did not feel himself bound by his agreement with the British government to abstain from further conspiracy; and finding himself at Philadelphia in the company of Reynolds, Rowan and Napper Tandy, he went to Paris to persuade the French government to send an expedition to invade Ireland. In February 1796 he arrived in Paris and had interviews with De La Croix and Carnot, who were impressed by his energy, sincerity and ability. A commission was given him as adjutant-general in the French army, which he hoped might protect him from the penalty of treason in the event of capture by the English; though he himself claimed the authorship of a proclamation said to have been issued by the United Irishmen, enjoining that all Irishmen taken with arms in their hands in the British service should be instantly shot; and he supported a project for landing a thousand criminals in England, who were to be commissioned to burn Bristol and commit other atrocities. He drew up two memorials representing that the landing of a considerable French force in Ireland would be followed by a general rising of the people, and giving a detailed account of the condition of the country.

The French Directory, which possessed information from Lord Edward FitzGerald and Arthur O'Connor confirming Tone, prepared to despatch an expedition under Louis Lazare Hoche. On 15 December 1796 the expedition, consisting of forty-three sail and carrying about 14,000 men with a large supply of war material for distribution in Ireland, sailed from Brest. Tone, who accompanied it as "Adjutant-general Smith," had the greatest contempt for the seamanship of the French sailors, who were unable to land due to severe gales. They waited for days off Bantry Bay, waiting for the winds to ease, but eventually gave it up. Returning to France, Tone served for some months in the French army under Hoche; and in June 1797 he took part in preparations for a Dutch expedition to Ireland, which was to be supported by the French. But the Dutch fleet was detained in the Texel for many weeks by unfavourable weather, and before it eventually put to sea in October, only to be crushed by Duncan in the battle of Camperdown, Tone had returned to Paris; and Hoche, the chief hope of the United Irishmen, was dead. Napoleon Bonaparte, with whom Tone had several interviews about this time, was much less disposed than Hoche had been to undertake in earnest an Irish expedition; and when the rebellion broke out in Ireland in 1798 he had started for Egypt. When, therefore, Tone urged the Directory to send effective assistance to the Irish rebels, all that could be promised was a number of small raids to descend simultaneously on different points of the Irish coast. One of these under General Humbert succeeded in landing a force in Killala Bay, and gained some success in Connacht (particularly at Castlebar) before it was subdued by Lake and Charles Cornwallis. Wolfe Tone's brother Matthew was captured, tried by court-martial, and hanged; a second raid, accompanied by Napper Tandy, came to disaster on the coast of Donegal; while Wolfe Tone took part in a third, under Admiral Bompard, with General Hardy in command of a force of about 3000 men, which encountered an English squadron near Lough Swilly on 12 October 1798. Tone, who was on board the Hoche, refused Bompard's offer of escape in a frigate before the action, and was taken prisoner when the Hoche was forced to surrender.

When the prisoners were landed a fortnight later Sir George Hill recognized Tone in the French adjutant-general's uniform. At his trial by court-martial in Dublin, Tone made a speech avowing his determined hostility to England and his intention "by fair and open war to procure the separation of the Two countries", and pleading in virtue of his status as a French officer to die by the musket instead of the rope. He was, however, sentenced to be hanged on 12 November 1798; but he cut his throat with a penknife, and died of the wound several days later.

WolfeToneStatue.JPG

Although Wolfe Tone had none of the attributes of greatness, "he rises", says Lecky, "far above the dreary level of commonplace which Irish conspiracy in general presents. The tawdry and exaggerated rhetoric; the petty vanity and jealousies; the weak sentimentalism; the utter incapacity for proportioning means to ends, and for grasping the stern realities of things, which so commonly disfigure the lives and conduct even of the more honest members of his class, were wholly alien to his nature. His judgment of men and things was keen, lucid and masculine, and be was alike prompt in decision and brave in action." Lecky was an ardent Hibernophile.

In his later years he overcame the drunkenness that was habitual to him in youth; he developed seriousness of character and unselfish devotion to what he believed was the cause of patriotism; and he won the respect of men of high character and capacity in France and Holland. His journals, which were written for his family and intimate friends, give a singularly interesting and vivid picture of life in Paris in the time of the directory. They were published after his death by his son, William Theobald Wolfe Tone (1791 - 1828), who was educated by the French government and served with some distinction in the armies of Napoleon, emigrating after Waterloo to America, where he died, in New York City, on 10 October 1828.

See Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone by himself, continued by his son, with his political writings, edited by W. T. Wolfe Tone (2 volumes., Washington, 1826), another edition of which is entitled Autobiography of Theobald Wolfe Tone, edited with introduction by R. Barry O'Brien (2 vols., London, 1893); R. R. Madden, Lives of the United Irishmen (7 vols., London, 1842); Alfred Webb, Compendium of Irish Biography (Dublin, 1878); W. E. H. Lecky, History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century, vols. iii., iv., v. (cabinet ed., 5 vols., London, 1892).

Original text from http://1911encyclopedia.orgfr:Theobald Wolfe Tone ga:Theobald Wolfe Tone