Boston molasses disaster

|

|

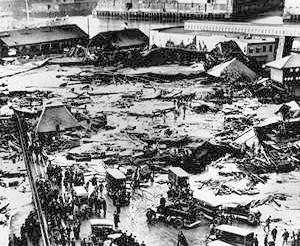

The Boston Molasses Disaster (also known as the Great Molasses Flood) occurred on January 15, 1919, in the North End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. A large molasses (treacle) tank burst and a wave of molasses ran through the streets at an estimated 60 km/h, killing twenty-one and injuring 150 others. The event has entered local folklore, and residents claim that the area still sometimes smells of molasses.

| Contents |

Sequence of events

Boston_molasses_area_map.png

The disaster occurred at the Purity Distilling Company facility on January 15, 1919, one day before the Eighteenth Amendment enabling Prohibition was ratified. At the time, molasses was the standard sweetener for North America (it has now been replaced by sugar). Molasses was also fermented (producing ethyl alcohol) for use in making liquor and as a key component in the manufacture of munitions. The stored molasses was awaiting transfer to the Purity plant situated between Willow Street and what is now named Evereteze Way in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

At 529 Commercial Street, a huge molasses tank (50 ft (15 m) tall, 240 ft (70 m) around and containing as much as 2.5 million US gallons (9,500 m³ or 9,500,000 liters) collapsed. The collapse unleashed an immense wave of molasses between 8 and 15 ft (2.5 to 4.5 m) high, moving at 35 mph (60 km/h) and exerting a pressure of 2 ton/ft² (200 kPa). The molasses wave was of sufficient force to break the girders of the adjacent Boston Elevated Railway's Atlantic Avenue Elevated structure and lift a train off the tracks. Several nearby buildings were also destroyed, and several blocks were flooded to a depth of 2 to 3 feet. Twenty-one people were killed and 150 injured as the molasses crushed and asphyxiated many of the victims to death. Rescuers found it difficult to make their way through the syrup to help the victims.

Boston_molasses_detail_map.png

It took over six months to remove the molasses from the cobblestone streets, theaters, businesses, automobiles, and homes. The harbor ran brown until summer. Local residents brought a class-action lawsuit (one of the first held in Massachusetts) against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company, which had bought Purity Distilling in 1917. In spite of the company's attempts to claim that the tank had been blown up by anarchists, it ultimately paid out $1 million in out-of-court settlements (equivalent to around $11 million as of 2005).

United States Industrial Alcohol, the parent company of Purity, did not rebuild the tank. The property became a yard for the Boston Elevated Railway (predecessor to the MBTA) and is currently the site of a city-owned baseball field.

To this day, people say that molasses left from this disaster still seeps up from some of the streets on a hot day.

Causes

The cause of the accident is not known with certainty. One possible explanation is that the tank may have been shoddily constructed, insufficiently tested, and overfilled. Another is that it may have burst due to fermentation occurring within (the carbon dioxide this would have produced would have raised the pressure inside the tank); this would probably have been helped by the unusual increase in the local temperatures that occurred over the previous day: the air temperature rose from 2°F to 40 °F (−17 °C to 4 °C) over that period. A third possibility is that the rising temperatures alone were enough to cause the collapse.

An inquiry after the disaster revealed that Arthur Jell, who oversaw the construction, neglected basic safety tests, such as filling the tank with water to check for leaks. When filled with molasses, the tank leaked so badly that it was painted brown to hide the leaks; in spite of this, local residents would come by to collect leaked molasses for their homes.

Accounts relate that given the timing of the accident, the tank may have been overfilled so that the owners could produce as much ethanol (for liquor) as possible before Prohibition came into effect. In fact, the Eighteenth Amendment would not become law for another year, and the Volstead Act would not ban the operations of industrial alcohol producers.

Further reading

- Puleo, Stephen Dark Tide : The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, Beacon Press; (September 2003) ISBN 0807050202

Boston-molasses-disaster-nyt-article.jpg

External links

- Molasses flood site, present-day pictures and list of 1919 inhabitants (http://www.gcrek.net/media/media-status.html)

- Equistar Chemicals, successor to United States Industrial Alcohol (Purity's parent company) (http://www.equistar.com/)

- What caused the great Boston Molasses Flood? (http://www.masshist.org/library/faqs.cfm#flood) from the Massachusetts Historical Society

- The Molasses Disaster of January 15, 1919 (http://edp.org/molyank.htm) Reprinted from Yankee Magazine

- A scanned newspaper article from 1919 (http://members.tripod.com/~earthdude1/molasses/molasses.jpg)

- An interview with Stephen Puleo, the author of the book above (http://www.bostonphoenix.com/boston/news_features/this_just_in/documents/03521177.asp)

References

- Was Boston once literally flooded with molasses? (http://www.straightdope.com/columns/041231.html) by The Straight Dope

- U.S. Industrial Alcohol timeline on Google Answers (http://answers.google.com/answers/threadview?id=353499)

- CNN.com story about the disaster (http://www.cnn.com/2004/US/Northeast/01/23/molasses.flood.ap/)he:אסון הדבשה של בוסטון