Taiji

|

|

Taiji may also mean:

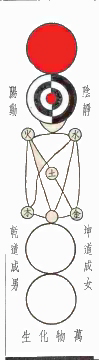

The Taiji (Traditional Chinese characters: 太極, the 'Supreme Ultimate'; Pinyin: tàijí; Wade-Giles: T'ai Chi; Cantonese IPA: []; Jyutping: tai3gik6; Japanese: Taikyoku; Korean: Taeguk, Taegeuk or T'aegŭk) is a concept introduced in the Zhuang Zi and so has an early connection with Taoism (pronounced "Daoism"). However, it also appears in the Xì Cí (Great Appendix) of the I Ching, (Yì Jíng or Book of Changes). The Taiji is understood to be the highest conceivable principle, that from which existence flows. In contemporary terms, the Taiji is the infinite, essential, and fundamental principle of evolutionary change that actualizes all potential states of being through the self-organizing integration of complementary existential polarities. More simply, it is the co-substantial union of yin and yang, the two opposing qualities of all things. In order for 'hot' to exist, so must 'cold.' The existence of 'hot,' in fact, is wholly dependent on the existence of 'cold' and ultimately arises from it, just as the existence of 'cold' in turn arises from that of 'hot' and is wholly dependent thereupon.

Note that as the highest conceivable principle, the Taiji is still superseded by the Tao (Dào) itself, the inconceivable essence of reality, which is by nature ineffable and beyond description. This 'ultimate reality' is that which cannot be named, although through conceptualizations such as the Taiji, the Tao can be approached.

When Confucianism came to the fore again during the Song Dynasty, it synthesized aspects of Buddhism and Taoism, and drew them together using threads that traced back to the earliest metaphysical discussions in the appendices to the Book of Changes.