Musical notation

|

|

Music notation is a system of writing for music. The term sheet music is used for written music to distinguish from audio recordings. In sheet music for ensembles, a score shows music for all players together, while parts contain only the music played by an individual musician. A score can be constructed (laboriously) from a complete set of parts and vice versa.

Present day standard music notation is based on a five-line staff with symbols for each note showing duration and pitch in twelve tone equal temperament. Pitch is shown using the diatonic scale, with accidentals to allow notes on the chromatic scale, and duration is shown in beats and fractions of a beat.

| Contents |

|

2.1 Elements of the staff |

Origins

There is some evidence that a kind of musical notation was practiced by the Egyptians from the 3rd millennium BC and by others in the Orient in ancient times.

Ancient Greece had a sophisticated form of musical notation, which was in use from at least the 6th century BC until approximately the 4th century AD; many fragments of compositions using this notation survive. The notation consists of symbols placed above text syllables. An example of a complete composition — indeed the only surviving complete composition using this notation — is the Seikilos epitaph, which has been variously dated between the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD.

Knowledge of the ancient Greek notation was lost around the time of the fall of the Roman Empire. Scholar and music theorist Isidore of Seville, writing in the early 7th century, famously remarked that it was impossible to notate music. By the middle of the 9th century, however, a form of notation began to develop in monasteries in Europe for Gregorian chant, using symbols known as neumes; the earliest surviving musical notation of this type is in the Musica disciplina of Aurelian of R��me, from about 850. There are scattered survivals from the Iberian peninsula before this time of a type of notation known as Visigothic neumes, but its few surviving fragments have not yet been deciphered.

Other types of notation date from the 10th century in China and Japan. In East Asia, as later in India and elsewhere in Asia, music was notated with the use of characters for sounds. Rhythmic motifs could also be prescribed in a similar way. In Europe, on the other hand, the foundations were laid for a purely symbolic notation of music, which does not seem to have been brought to existence anywhere else.

Standard notation described

Elements of the staff

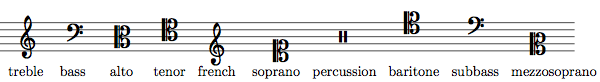

A staff (in British English, also stave) is generally presented with a clef, which indicates the particular range of pitches encompassed by the staff. A treble clef placed at the beginning of a line of music indicates that the lowest line of the staff represents the note E above middle C, while the highest line represents the note F one octave higher. Other common clefs include the bass clef (second G below middle C to A below middle C), alto clef (F below middle C to G above middle C) and tenor clef (D below middle C to E above middle C). These last two clefs are examples of C clefs, in which the line pointed to by the clef should be interpreted as a middle C. In a similar fashion, the treble clef points to a G and the bass clef points to an F.

In early music, the clef was written as a letter and its location on the staff was chosen by the writer. The treble clef and bass clef used today are stylized versions of the letters G and F, respectively. Their locations are now standardized. Unusual clefs are used for certain requirements, such as the low G clef used for classical guitar music and tenor parts in choral music.

Following the clef, the key signature on a staff indicates the key of the piece by specifying certain notes to be held flat or sharp throughout the piece, unless otherwise indicated. The key signature is presented in the order of the circle of fifths, with flats B-E-A-D-G-C-F and sharps in the opposite order, F-C-G-D-A-E-B.

Another common element of a staff is the time signature, which indicates the rhythmic characteristics of the piece. Time signatures generally consist of two numbers; the upper number indicates the number of beats per measure (or "bar"), while the lower indicates what sort of note constitutes a "beat". A time signature of 4/4 (also known as "common time" and sometimes indicated with a large "C" symbol) implies that there will be four beats per measure, with each beat constituting a quarter note. A signature of 2/2 (or "cut time", a "C" with a vertical slash) allows 2 beats per measure, with each half note lasting a beat. This is important, because the first beat of each bar is generally stressed. Less commonly, music that lacks rigid rhythmic organization is written without a time signature.

Notes representing a pitch outside of the scope of the five line staff can be represented using leger lines, which provide a single note with additional lines and spaces. Octave (8va) notation is used, particularly for keyboard music, where notes are substantially above or below the staff.

Multiple staves can be grouped together to form a staff system. A system is used where two staves are required to cover the range of the instrument (as with a keyboard instrument), or where multiple related instruments are played (as with three violin parts on a score). A score for ensemble music includes multiple systems, as does most organ music (where the pedals are written as a separate system).

Various directions to the player regarding matters such as tempo and dynamics are added above or below the staff, often in Italian (sometimes abbreviated). For vocal music, lyrics are written.

Here is a sample illustrating some common musical notation.

- Missing image

Wtk1-fugue2-page1-mm1-9.png

Sample of common musical notation (J.S. Bach's Fuga a 3 Voci, typeset in LilyPond.

- Missing image

Audiobutton.png

Image:Audiobutton.png

Listen to this piece

Development of music notation

The ancestors of modern symbolic music notation originated in the Catholic church, as monks developed methods to put plainchant (sacred songs) to paper. The earliest of these ancestral systems, from the 8th century, did not originally utilise a staff, and used neum (or neuma or pneuma), a system of dots and strokes that were placed above the text. Although capable of expressing considerable musical complexity, they could not exactly express pitch or time and served mainly as a reminder to one who already knew the tune, rather than a means by which one who had never heard the tune could sing it exactly at sight.

To address the issue of exact pitch, a staff was introduced consisting originally of a single horizontal line, but this was progressively extended until a system of four parallel, horizontal lines was standardised on. The vertical positions of each mark on the staff indicated which pitch or pitches it represented (pitches were derived from a musical mode, or key). Although the 4-line staff has remained in use until the present day for plainchant, for other types of music, staffs with differing numbers of lines have been used at various times and places for various instruments. The modern system of a universal standard 5-line staff was first adopted in France, and became widely used by the 16th century (although the use of staffs with other numbers of lines was still widespread well into the 17th century).

Because the neum system arose from the need to notate songs, exact timing was initially not a particular issue as the music would generally follow the natural rhythms of the Latin language. However, by the 10th century a system of representing up to four note lengths had been developed. These lengths were relative rather than absolute, and depended on the duration of the neighboring notes. It was not until the 14th century that something like the present system of fixed note lengths arose. Starting in the 15th century, vertical bar lines were used to divide the staff into sections. These did not initially divide the music into measures of equal length (as most music then featured far fewer regular rhythmic patterns than in later periods), but appear to have been introduced as an aid to the eye for "lining up" notes on different staves that were to be played or sung at the same time. The use of regular measures became commonplace by the end of the 17th century.

It is worth noting that standard notation was originally developed for use with voice. Proponents of other systems claim that standard notation is less than ideally suited to instrumental music.

Symbols used in modern musical notation

The following table shows some of the symbols used in Modern musical notation.

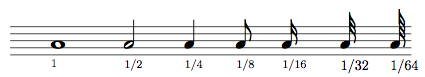

| Notes (in decreasing length) |

|

| Rests (in decreasing length) | Missing image Music_rests.png Rests |

| Clefs |

|

See also: Da capo, Dal Segno, Coda, Fermata, Accent.

Terms for note durations in American and British English:

| duration | American | British |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | double whole note | breve |

| 1 | whole note | semibreve |

| 1/2 | half note | minim |

| 1/4 | quarter note | crochet |

| 1/8 | eighth note | quaver |

| 1/16 | sixteenth note | semiquaver |

| 1/32 | thirty-second note | demisemiquaver |

| 1/64 | sixty-fourth note | hemidemisemiquaver |

| 1/128 | hundred twenty-eighth note | quasihemidemisemiquaver |

In U.S. parlance, semibreve and minim are used only in discussions of early music; whole note and half note are used in other contexts. The breve is rarely used in baroque and later eras. When it appears, it is written as oo or |O|.

Effects

According to Philip Tagg (1979, p.28-32) and Richard Middleton (1990, p.104-6) musicology and to a degree European-influenced musical practice suffer from a 'notational centricity', "a methodology slanted by the characteristics of notation."

"Musicological methods tend to foreground those musical parameters which can be easily notated...they tend to neglect or have difficulty with parameters which are not easily notated", such as Fred Lerdahl. "Notation-centric training induces particular forms of listening, and these then tend to be applied to all sorts of music, appropriately or not."

Notational centricity also encourages "reification: the score comes to be seen as 'the music', or perhaps the music in an ideal form."

Other notation systems

Figured bass

Main article: Figured bass

Figured bass notation originated in baroque basso continuo parts. It is also used extensively in accordion notation, and for jazz. For continuo and jazz parts, it implies improvisation by the performer; for accordion, it is used to notate the bass button to be used.

Shape note

Main article: Shape note

The shape note system is found in some church hymnals, sheet music, and song books, especially in the American south. Instead of the customary elliptical note head, note heads of various shapes are used to show the position of the note on the major scale. Sacred Harp is one of the most popular tune books using shape notes.

Popular music

Fake books (and the Real Books) utilize standard notation, but with key signatures only on the beginning stave, for the melodic line with letter notation for chord names, chord symbols, written above. Improvisation is implied and this system is used for jazz and popular music. See Berklee College of Music.

Letter notation

The notes of the 12-tone scale can be written by their letter names, possibly with a trailing sharp or flat symbol. This is most often used when speaking about music or writing about it. Letter notation is used to identify chords.

In both cases notes must be named for their diatonic functionality. Tonic Sol-fa is a type of notation using the initial letters of solfege.

Solfege

Main article: Solfege

Solfege is a way of assigning syllables to names of the musical scale. In order, they are today: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti, and Do (for the octave). Another common variations is: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Si, Do. These functional names of the musical notes were introduced by Guido of Arezzo (c.991 – after 1033) using the beginning syllables of the six lines of the Latin hymn Ut queant laxis. The original sequence was Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La. "Ut" became later "Do". See also: solfege, sargam

Numbered notation

Main article: Numbered musical notation

The numbered musical notation system, better known as jianpu, meaning "simplified notation" in Chinese, is widely used among the Chinese people and probably some other Asian communities. Numbers 1 to 7 represent the seven notes of the diatonic major scale, and number 0 represents the musical rest. Dots above a note indicate octaves higher, and dots below indicate octaves lower. Underlines of a note or a rest shorten it, while dots and dashes after lengthen it. The system also makes use of many symbols from the standard notation, such as bar lines, time signatures, accidentals, tie and slur, and the expression markings.

Cipher notation

In many cultures, including Chinese, Indonesian and Indian (sargam), the "sheet music" consists primarily of the numbers, letters or native characters representing notes in order. Those different systems are collectively know as cipher notations. The numbered notation is an example, so are letter notation and solfege if written in musical sequence.

Braille music

Main article: Braille music

Braille music is a complete, well developed, and internationally accepted musical notation system that has symbols and notational conventions quite independent of print music notation. It is linear in nature, similar to a printed language and different from the two-dimensional nature of standard printed music notation. To a degree Braille music resembles musical markup languages (http://www.musicmarkup.info/scope/markuplanguages.html) such as XML for Music (http://emusician.com/ar/emusic_xml_music/) or NIFF. See Braille music.

Integer notation

In integer notation, or the integer model of pitch, all pitch classes and intervals between pitch classes are designated using the numbers 0 through 11, as in modulo 12. It is not used to notate music for performance, but is a common analytical and compositional tool when working with twelve tone, serial, or otherwise atonal music. Pitch classes can be notated in this way by assigning the number 0 to some note - C natural by convention - and assigning consecutive integers to consecutive semitones; so if 0 is C natural, 1 is C sharp, 2 is D natural and so on up to 11 which is B natural. The C above this is not 12, but 0 again (12-12=0). Thus the system represents complete octave equivalency. One advantage of this system is that it ignores the "spelling" of notes (B sharp, C natural and D double-flat are all 0) according to their diatonic functionality. Thus the system represents complete enharmonic equivalency.

One drawback is that pitches, intervals, and simultaneities (chords) are all notated in the same manner. 4, for instance, indicates the arbitrarily decided fourth pitch (E, if C=0), or two pitches four semitones apart (such as 0 and 4 or 2 and 6). 024 indicates a simultaneity or succession (such as a melodic fragment) consisting of three notes, each a whole tone apart (for example, C, D and E, or G sharp, B flat and C) and the first and last a major third apart. This notation may be used to represent all traditional permutations of a tone row or set in a matrix.

The integer model of pitch is one of the basis of atonal or set theoretical techniques in musical analysis, which now may include diatonic set theory and tonal music. It carries an added advantage in that one is able to prove many things, within limits, about pitch or pitches, and even tonal constructs. Like integers, pitches may be evenly spaced and ordered from lower to higher (lesser to greater for integers), while many things are not true of both integers and pitch.

Tablature

Main article: Tablature

Tablature was first used in the Renaissance for lute music. A staff is used, but instead of pitch values, the fret or frets to be fingered are written instead. Rhythm is written separately and durations are relative and indicated by horizontal space between notes. In later periods, lute and guitar music was written with standard notation. Tablature was again used in the late 20th century and early 21st century for popular guitar music and other fretted instruments, being easy to transcribe and share over the internet in ASCII format. Websites like OLGA.net (http://www.olga.net/) have archives of text-based popular music tablature.

Klavar notation

Main article: Klavar notation

Klavar notation is a chromatic system of notation geared toward keyboard instruments, that is said by its adherents to be easier to learn than standard notation. A considerable body of repertoire has been transcribed to Klavar notation.

Graphic notation

Main article: Graphic notation (music)

The term 'graphic notation' refers to the contemporary use of non-traditional symbols and text to convey information about the performance of a piece of music. It is used for experimental music, which in many cases is difficult to transcribe in standard notation. Practitioners include Christian Wolff, Earle Brown, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Krzysztof Penderecki, Cornelius Cardew, and Roger Reynolds. See Notations, edited by John Cage and Alison Knowles, ISBN 0685148645.

Parsons code

Main article: Parsons code

Parsons code is used to encode music in a method which can be easily searched. This style is designed to be used by individuals without any musical background.

Systems not based on the standard 12-tone scale

Other systems exist for non twelve tone equal temperament and non-Western music, such as the Indian svar lippi, along with other alternatives such as Ailler-Brennink. Some cultures use their own cipher notations for those music. Sometimes the pitches of music written in just intonation are notated with the frequency ratios, while Ben Johnston has devised a system for representing just intonation with traditional western notation and the addition of accidentals which indicate the cents a pitch is to be lowered or raised.

See also

- Guido of Arezzo

- List of musical topics

- Music theory

- Time unit box system

- Scorewriters are software tools used for publishing sheet music.