Sassanid dynasty

|

|

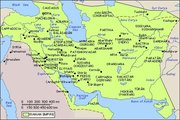

The Sassanid dynasty (also Sassanian) was the name given to the kings of Persia during the era of the second Persian Empire, from 224 until 651, when the last Sassanid shah, Yazdegerd III, lost a 14-year struggle to drive out the Umayyad Caliphate, the first of the Islamic empires.

| Contents |

The Empire

Sassanian_king.jpg

The Sassanid era began in earnest in 228, when the Shah Ardashir I destroyed the Parthian Empire which had held sway over the region for centuries. He and his successors created a vast empire, based in Firouzabad, Fars, which included those lands of the old Achaemenid Persian empire east of the Euphrates River. The Sassanids wanted to recreate the glories of ancient Iran and claimed to Persianise the country. They made Zoroastrianism the state religion and claimed in inscriptions to have persecuted other faiths (although these claims are not reflected in native Jewish and Christian sources of the time). It was the shahs' long sought-after goal to reunify all of the old Achaemenid territory, which brought them into frequent wars against the Roman Empire and Byzantine Empire.

Ardeshir's son Shapur I (241–272) continued this expansion, conquering Bactria and Kushan, while leading several campaigns against Rome. In 259, the Persian army defeated the Roman emperor Valerian at the battle of Edessa where more than 70,000 Roman soldiers were captured or slain. Valerian then tried to negotiate a peace with Shapur, but was captured by treachery and taken into captivity. Shapur used Valerian as a human stepping-stool to assist the Persian king in mounting his horse, thus subjecting a Roman emperor to the ultimate humiliation by a foreign leader. Valerian's body was later skinned to produce a lasting trophy of Roman submission.

Near the end of the 5th century a new enemy, the barbaric Hephthalites, or "White Huns," attacked Persia; they defeated the Persian king Firuz (or Peroz) I in 483 and for some years thereafter exacted heavy tribute. It was not until the reign of Khosroe (or Khosrau) I (531–579), one of the greatest Sassanian rulers, that the Huns were beaten. Khosro I (531-579), also known as Anushirvan the Just, is the most celebrated of the Sassanid rulers. He reformed the tax system and reorganized the army and the bureaucracy, tying the army more closely to the central government than to local lords. His reign witnessed the rise of the dihqans (literally, village lords), the petty landholding nobility who were the backbone of later Sassanid provincial administration and the tax collection system. Khosro was a great builder, embellishing his capital, founding new towns, and constructing new buildings. He rebuilt the canals and restocked the farms, which had been destroyed in the wars. He built strong fortifications at the passes and placed subject tribes in carefully chosen towns on the frontiers, so that they could act as guardians of the state against invaders.

Justinian paid Khosrow 440,000 pieces of gold as a bribe to keep the peace, but he seems to have been a man who genuinely enjoyed the fruits of peace and saw no reason to continue a senseless war. He was tolerant of all religions, though he decreed that Zoroastrianism should be the official state religion, but he was not unduly disturbed when one of his sons became a Christian. Under his auspices, too, many books were brought from India and translated into Pahlavi. Some of these later found their way into the literature of the Islamic world.

System of Governing

| It is requested that this article, or a section of this article, be expanded See the request on the listing or elsewhere on this talk page. Once the improvements have been completed, you may remove this notice and the page's listing. |

Naqshe_rostam.jpg

The Sassanids established an empire roughly within the frontiers achieved by the Achaemenids, with the capital at Ctesiphon. The Sassanids consciously sought to resuscitate Iranian traditions and to obliterate Greek cultural influence. Their rule was characterized by considerable centralization, ambitious urban planning, agricultural development, and technological improvements. Sassanid rulers adopted the title of shahanshah (king of kings), as sovereigns over numerous petty rulers, known as shahrdars. Historians believe that society was divided into four classes: the priests, warriors, secretaries, and commoners. The royal princes, petty rulers, great landlords, and priests together constituted a privileged stratum, and the social system appears to have been fairly rigid. Sassanid rule and the system of social stratification were reinforced by Zoroastrianism, which became the state religion. The Zoroastrian priesthood became immensely powerful. The head of the priestly class, the mobadan mobad, along with the military commander, the eran spahbod, and the head of the bureaucracy, were among the great men of the state. Rome, with its capital at Constantinople, had replaced Greece as Iran's principal Western enemy, and hostilities between the two empires were frequent. Shapur I (240-272), son and successor of Ardeshir, waged successful campaigns against the Romans and in 260 even took the emperor Valerian prisoner. Between 260 and 263 he had lost his conquest to Odenathus, and ally of Rome. Shapur II (ruled 309-379) regained the lost territories, however, in three successive wars with the Romans.

Sassanid army

Derafsh.gif

Taghebostan.jpg

The Iranian society under the Sassanids was divided-allegedly by Ardashir I, into four groups: priests, warriors (artetdar), state officials, and artisans and peasants. The second category embraced princes, lords, and landed aristocracy, and one of the three great fires of the empire, Adur Gunasp at iz (Takht-e Soleyman in Azerbaijan) belonged to them. With a clear military plan aimed at the revival of the Iranian Empire, Ardashir I, formed a standing army which was under his personal command and its officers were separate from satraps and local princes and nobility. Ardedhir had started as the military commander of Darabgerd, and was knowledgeable in older and contemporary military history, from which he benefited, as history shows, substantially. For he restored Achaemenid military organizations, retained Parthian cavalry, and employed new-style armour and siege-engines, thereby creating a standing army (Middle Persian 'spah') which served his successors for over four centuries, and defended Iran against Central Asiatic nomads and Roman armies.

The backbone of the army was its heavy cavalry "in which all the nobles and men of rank" underwent "hard service" and became professional soldiers "through military training and discipline, through constant exercise in warfare and military manoeuvres". From the third century the Romans also formed units of heavy cavalry of the Oriental type; they called such horsemen clibanarii "mailclad [riders]", a term thought to have derived from an Iranian (griwbanar - griwbanwar - griva-pana-bara "neck-guard wearer"). The heavy cavalry of Shapur II is described by an eye-witness historian as follows:

"all the companies were clad in iron, and all parts of their bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff-joints conformed with those of their limbs; and the forms of human faces were so skilfully fitted to their heads, that since their entire body was covered with metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where through the tip of their nose they were able to get a little breath. Of these some who were armed with pikes, stood so motionless that you would have thought them held fast by clamps of bronze".

The described horsemen are represented by the seventh-century knight depicting Emperor Khosrow Parvez on his steed abdiz on a rock relief at Taq-e Bostan in Kermanshah. Since the Sassanid horseman lacked the stirrup, he used a war saddle which, like the medieval type, had a cantle at the back and two guard clamps curving across the top of the rider's thighs enabling him thereby to stay in the saddle especially during violent contact in battle. The inventory of weapons ascribed to Sassanid horsemen at the time of Khosrow Anoshiravan, resembles the twelve items of war mentioned in Vendidad 14.9, thus showing that this part of the text had been revised in the later Sassanid period.

More interestingly, the most important Byzantine treatise on the art of war, the Strategicon, also written at this period, requires the same equipments from a heavily-armed horseman. This was due to the gradual orientalisation of the Roman army to the extent that in the sixth century "the military usages of the Romans and the Persians become more and more assimilated, so that the armies of Justinian and Khosrow are already very much like each other;" and, indeed, the military literatures of the two sides show strong affinities and interrelations. According to the Iranian sources mentioned above, the martial equipments of a heavily-armed Sassanian horseman were as follows: helmet, hauberk (Pahlavi griwban), breastplate, mail, gauntlet (Pahlavi abdast), girdle, thigh-guards (Pahlavi ran-ban), lance, sword, battle-axe, mace, bowcase with two bows and two bowstrings, quiver with 30 arrows, two extra bowstrings, spear, and horse armour (zen-abzar); to these some have added a lasso (kamand), or a sling with slingstones. The elite corps of the cavalry was called "the Immortals," evidently numbering-like their Achaemenid namesakes 10,000 men. On one occasion (under emperor Bahram V) the force attacked a Roman army but outnumbered, it stood firm and was cut down to a man. Another elite cavalry group was the Armenian one, whom the Persians accorded particular honour. In due course the importance of the heavy cavalry increased and the distinguished horseman assumed the meaning of "knight" as in European chivalry; if not of royal blood, he ranked next to the members of the ruling families and was among the king's boon companions.

The Sassanids did not form lightly-armed cavalry but extensively employed-as allies or mercenaries-troops from warlike tribes who fought under their own chiefs. "The Sagestani were the bravest of all"; the Gelani, Albani and the Hephthalites, the Kushans and the Khazars were the main suppliers of light-armed cavalry. The skill of the Dailamites in the use of sword and dagger made them valuable troopers in close combat, while Arabs were efficient in desert warfare.

The infantry (paygan) consisted of the archers and ordinary footmen. The former were protected "by an oblong curved shield, covered with wickerwork and rawhide". Advancing in close order, they showered the enemy with storms of arrows. The ordinary footmen were recruited from peasants and received no pay, serving mainly as pages to the mounted warriors; they also attacked walls, excavated mines and looked after the baggage train, their weapons being a spear and a shield. The cavalry was better supported by war elephants "looking like walking towers", which could cause disorder and damage in enemy ranks in open and level fields. War chariots were not used by the Sassanians. Unlike the Parthians, however, the Iranians organised an efficient siege machine for reducing enemy forts and walled towns. They learned this system of defence from the Romans but soon came to match them not only in the use of offensive siege engines-such as scorpions, balistae, battering rams, and moving towers-but also in the methods of defending their own fortifications against such devices by catapults, by throwing stones or pouring boiling liquid on the attackers or hurling fire brands and blazing missiles.

The organisation of the Sassanid army is not quite clear, and it is not even certain that a decimal scale prevailed, although such titles as hazarmard might indicate such a system. Yet the proverbial strength of an army was 12,000 men. The total strength of the registered warriors in 578 was 70,000. The army was divided, as in the Parthian times, into several gunds, each consisting of a number of drafs (units with particular banners), each made up of some Wats. The imperial banner was the Draf-a Kavian, a talismanic emblem accompanying the King of Kings or the commander-in-chief of the army who was stationed in the centre of his forces and managed the affairs of the combat from the elevation of a throne. At least from the time of Khosrow Anoiravan a seven-grade hierarchical system seems to have been favoured in the organisation of the army. The highest military title was arghed which was a prerogative of the Sassanian family. Until Khosrow Andoiravan's military reforms, the whole of the Iranian army was under a supreme commander, Eran-spahbed, who acted as the minister of defence, empowered to conduct peace negotiations; he usually came from one of the great noble families and was counted as a counselor of the Great King.

Along with the revival of "heroic" names in the middle of the Sassanid period, an anachronistic title, artetaran salar was coined to designate a generalissimo with extraordinary authority, but this was soon abandoned when Anoshiravan abolished the office of Eran-spahbed and replaced it with those of the four marshals (spahhed) of the empire, each of whom was the military authority in one quarter of the realm. Other senior officials connected with the army were: Eran-ambaragbed "minister of the magazines of empire," responsible for the arms and armaments of warriors; the marzbans "margraves"-rulers of important border provinces; kanarang-evidently a hereditary title of the ruler of Tus; gund-salar "general"; paygan-salar "commander of the infantry"; and pushtigban-salar "commander of the royal guard".

A good deal of what is known of the Sassanid army dates from the sixth and seventh centuries when, as the results of Anoshiravan's reforms, four main corps were established; soldiers were enrolled as state officials receiving pay and subsidies as well as arms and horses; and many vulnerable border areas were garrisoned by resettled warlike tribes. The sources are particularly rich in accounts of the Sassanid art of warfare because there existed a substantial military literature, traces of which are found in the Shahnama, Denkard 8.26-an abstract of a chapter of the Sassanian Avesta entitled Artetarestan "warrior code"-and in the extracts from the A'in-nama which Ebn Qotayba has preserved in his Oyun al-akhbar and Inostrantsev has explained in detail. The Artetarestan was a complete manual for the military: it described in detail the regulations on recruitments, arms and armour, horses and their equipments, trainings, ranks, and pay of the soldiers and provisions for them, gathering military intelligence and taking precaution against surprise attack, qualifications of commanders and their duties in arraying the lines, preserving the lives of their men, safeguarding Iran, rewarding the brave and treating the vanquished. The A'in-nama furnished valuable instructions on tactics, strategy and logistics. It enjoined, for instance, that the cavalry should be placed in front, left-handed archers capable of shooting to both sides be positioned on the left wing, which was to remain defensive and be used as support in case of enemy advance, the centre be stationed in an elevated place so that its two main parts (i. e., the chief line of cavalry, and the lesser line of infantry behind them) could resist enemy charges more efficiently, and that the men should be so lined up as to have the sun and wind to their back.

Battles were usually decided by the shock cavalry of the front line charging the opposite ranks with heavy lances while archers gave support by discharging storms of arrows. The centre, where the commander-in-chief took his position on a throne under the Derafsh Kaviani, was defended by the strongest units. Since the carrying of the shield on the left made a soldier inefficient in using his weapons leftwards, the right was considered the line of attack, each side trying to outflank the enemy from that direction, i.e., at the respective opponent's left; hence, the left wing was made stronger but assigned a defensive role. The chief weakness of the Iranian army was its lack of endurance in close combat. Another fault was the Iranian's too great a reliance on the presence of their leader: the moment the commander fell or fled his men gave way regardless of the course of action.

During the Sassanid period the ancient tradition of single combat (maid-o-maid) developed to a firm code. In 421 Emperor Bahram V opposed a Roman army but accepted the war as lost when his champion in a single contest was slain by a Goth from the Roman side. Such duels are represented on several Sassanid rock reliefs at Naksh-i Rustam, and on a famous cameo in Paris depicting Emperor Shapur I capturing Valerian.

Sassanid Emperors were conscious of their role as military leaders: many took part in battle, and some were killed; the Picture Book of Sassanid Kings showed them as warriors with lance or sword. Some are credited with writing manuals on archery, and they are known to have kept accounts of their campaigns ("When Kosrow Parvez concluded his wars with Bahram-e Choubina and consolidated his rule over the empire, he ordered his secretary to write down an account of those wars and related events in full, from the beginning to the end").

While heavy cavalry proved efficient against Roman armies, it was too slow and regimentalised to act with full force against agile and unpredictable light-armed cavalry and rapid foot archers; the Persians who in the early seventh century conquered Egypt and Asia Minor lost decisive battles a generation later when nimble, lightly armed Arabs accustomed to skirmishes and desert warfare attacked them. Hired light-armed Arab or East Iranian mercenaries could have served them much better.

Expansion to India

Main article: Indo-Sassanian

After The Sassanids came to power in Iran in 226 A.D. The second emperor, Shapur I (240-270), extended his authority eastwards into India and the previously autonomous Kushans were obliged to accept his suzerainty.

Successive Sassanid emperors were either tolerant of other religions or pursued policies of persecution, particularly against Christians, but in India the Kushans were generally tolerant of indigenous beliefs. Thanks to traded goods such as silverware and textiles depicting the Sassanid emperors engaged in hunting or administering justice, their imperial example became well known in Kushan India and, owing to the political relationship, it was wise for Kushan art to be seen to be drawing inspiration from Iran, imitation being one of the best forms of flattery. This adoption of Iranian forms, rather than Indian, also helped the Kushans to maintain their aloofness from their subjects.

Although the Kushan empire declined at the end of the 3rd century, leading to the rise to power of an indigenous Indian dynasty, the Guptas, in the 4th century, it is clear that Sassanid influence remained relevant in the north-west of India.

Decline

Ardeshir-kakh4.jpg

Khosrau II came close to achieving the Sassanid dream of restoring the Achaemenid boundaries when Jerusalem fell to him and Constantinople was under his siege in 626. However, Khosrau II had overextended his army and overtaxed the people. When the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in a tactical move abandoned his besieged capital and sailed up the Black Sea to attack Persia from the rear, there was no resistance. Heraclius then marched through Mesopotamia and western Persia sacking Takht-e Soleyman and the Palace of Dastgerd. After the death of Khosrau II, and over a period of 14 years and twelve successive kings, the Sassanid Empire weakened considerably, and the power of the central authority passed into the hands of the generals. The Sassanids never recovered.

In the spring of 633 a grandson of Khosrau called Yezdegerd ascended the throne, and in that same year the first Arab squadrons made their first raids into Persian territory. Years of warfare had exhausted both the Byzantines and the Iranians. The later Sassanids were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation, religious unrest, rigid social stratification, the increasing power of the provincial landholders, and a rapid turnover of rulers. These factors facilitated the Arab invasion in the seventh century. Internal dissension and a long brutal conflict with the Byzantines left Sassanid Persia prey for the Arabs.

This was the beginning of the end. Yezdegerd was a boy, at the mercy of his advisers, incapable of uniting a vast country which was crumbling into a number of small feudal kingdoms. Rome no longer threatened. The threat came from the small disciplined armies of Khalid ibn Walid, once one of Mohammad's chosen companion-in-arms and now, after the Prophet's death, the leader of the Arab army.

Art

| It is requested that this article, or a section of this article, be expanded See the request on the listing or elsewhere on this talk page. Once the improvements have been completed, you may remove this notice and the page's listing. |

ShapurII.jpg

Sassanian_silver_vessels.jpg

Sassanian_silver_plate.jpg

E3_5_4a_sassanian.jpg

In many ways the Sassanian period (224-633) witnessed the highest achievement of Persian civilization, and constituted the last great Iranian Empire before the Moslem conquest.

The Sassanian Dynasty, like the Achaemenian, originated in the province of Fars. They saw themselves as successors to the Achaemenians, after the Hellenistic and Parthian interlude, and perceived it as their role to restore the greatness of Iran.

At its peak, the Sassanian Empire stretched from Syria to north-west India; but its influence was felt far beyond these political boundaries. Sassanian motifs found their way into the art of central Asia and China, the Byzantine Empire, and even Merovingian France.

In reviving, the glories of the Achaemenian past, the Sassanians were no mere imitators. The art of this period reveals an astonishing virility. In certain respects it anticipates features later developed during the Islamic period. The conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great had inaugurated the spread of Hellenistic art into Western Asia; but if the East accepted the outward form of this art, it never really assimilated its spirit. Already in the Parthian period Hellenistic art was being interpreted freely by the peoples of the Near East and throughout the Sassanian period there was a continuing process of reaction against it. Sassanian art revived forms and traditions native to Persia; and in the Islamic period these reached the shores of the Mediterranean.

The splendour in which the Sassanian monarchs lived is well illustrated by their surviving palaces, such as those at Firouzabad and Bishapur in Fars, and the capital city of Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia. In addition to local traditions, Parthian architecture must have been responsible for a great many of the Sassanian architectural characteristics. All are characterised by the barrel-vaulted iwans introduced in the Parthian period, but now they reached massive proportions, particularly at Ctesiphon. The arch of the great vaulted hall at Ctesiphon attributed to the reign of Shapur I (241-272) has a span of more than 80 ft, and reaches a height of 118 ft. from the ground. This magnificent structure fascinated architects in the centuries that followed and has always been considered as one of the most important pieces of Persian architecture. Many of the palaces contain an inner audience hall which consists, as at Firuzabad, of a chamber surmounted by a dome. The Persians solved the problem of constructing a circular dome on a square building by the squinch. This is an arch built across each corner of the square, thereby converting it into an octagon on which it is simple to place the dome. The dome chamber in the palace of Firouzabad is the earliest surviving example of the use of the squinch and so there is good reason for regarding Persia as its place of invention.

The unique characteristic of Sassanian architecture, was its distinctive use of space. The Sassanian architect conceived his building in terms of masses and surfaces; hence the use of massive walls of brick decorated with molded or carved stucco. Stucco wall decorations appear at Bishapur, but better examples are preserved from Chal Tarkhan near Rayy (late Sassanian or early Islamic in date), and from Ctesiphon and Kish in Mesopotamia. The panels show animal figures set in roundels, human busts, and geometric and floral motifs.

At Bishapur some of the floors were decorated with mosaics showing scenes of merrymaking as at a banquet; the Roman influence here is clear, and the mosaics may have been laid by Roman prisoners. Buildings were also decorated with wall paintings; particularly fine examples have been found at Kuh-i Khwaja in Sistan.

Sassanid Empire timeline

226-241: Reign of Ardashir I

- 224-226: Overthrow of Parthian Empire.

- 229-232: War with Rome

- Zoroastrianism is revived as official religion.

- The collection of texts known as the Zend Avesta is assembled.

241-271: Reign of Shapur I

- 241-244: First war with Rome.

- 258-260: Second war with Rome. Capture of Roman emperor Valerian.

- 215-271: Mani, founder of Manicheanism.

271-301: A period of dynastic struggles

309-379: Reign of Shapur II "the Great"

- 337-350: First war with Rome.

- 358-363: Second war with Rome.

399-420: Reign of Yazdegerd I "the Sinner"

- 409: Christian are permitted to publicly worship and to build churches.

- 416-420: Persecution of Christians as Yazdegerd revokes his earlier order.

420-440: Reign of Bahram V.

- 420-422: War with Rome.

- 424: Council of Dad-Ishu declares the Eastern Church independent of Constantinople.

483: Edict of Toleration granted to Christians

491: Armenian Church repudiates the Council of Chalcedon.

- Nestorian Christianity becomes dominant Christian sect in Sassanid Empire

531-579: Reign of Khosrau I, "the Blessed" (Anushirvan)

533: "Treaty of Endless Peace" with Rome.

540-562: War with Rome.

590-628: Reign of Khosrau II

603-628: War with Rome. With conquests in Syria, Palestine, Egypt and Anatolia, Persia nearly restored to boundaries of Achaemenid dynasty, before being beaten back by Romans.

610: Arabs defeat a Sassanid army at Dhu-Qar.

626: Unsuccessful siege of Constantinople by Avars and Persians.

627: Roman Emperor Heraclius invades Assyria and Mesopotamia. Definitive defeat of Persian forces at the battle of Nineveh by Khazar-Roman alliance.

628-632: Chaotic period of multiple rulers.

632-642: Reign of Yazdegerd III

633: Decisive Sassanid defeat at the battle of Kadisiya begins Arab conquest of Persia.

642: Final victory of Arabs when Persian army destroyed at Nehawand.

651: Last Sassanid ruler Yazdegerd III murdered at Merv, present-day Turkmenistan, ending the dynasty.

Sassanid rulers

- Ardashir I from 224 to 241.

- Shapur I from 241 to 272

- Hormizd I from 272 to 273.

- Bahram I from 273 to 276.

- Bahram II from 276 to 293.

- Bahram III year 293.

- Narseh from 293 to 302.

- Hormizd II from 302 to 310.

- Shapur II from 310 to 379

- Ardashir II from 379 to 383.

- Shapur III from 383 to 388.

- Bahram IV from 388 to 399.

- Yazdegerd I from 399 to 420.

- Bahram V from 420 to 438.

- Yazdegerd II from 438 to 457.

- Hormizd III from 457 to 459.

- Peroz I from 457 to 484.

- Balash from 484 to 488.

- Kavadh I from 488 to 531.

- Khosrau I from 531 to 579.

- Hormizd IV from 579 to 590.

- Khosrau II from 590 to 628.

- Kavadh II year 628.

- Ardashir III from 628 to 630.

- Shahrbaraz year 630.

- Boran and others from 630 to 631.

- Hormizd VI (or V) from 631 to 632.

- Yazdegerd III from 632 to 651.

Family Tree of Sasanian Kings

See also

- List of kings of Persia

- Firouzabad

- Palace of Ardashir

- Ghal'eh Dokhtar, his first base.

- The Art of Sassanians (http://www.iranchamber.com/art/articles/art_of_sassanians.php|)

- Islamic Metalwork (http://www.islamicarchitecture.org/art/islamic-metalwork.html) The continuation of Sassanid Artbg:Сасанидско царство

cs:Dynastie Sásánovců de:Sassaniden es:Imperio Sasánida eo:Sasanidoj fa:ساسانیان fr:Sassanides la:Sassanidae nl:Sassaniden ja:サーサーン朝 pl:Sasanidzi sv:Sassanider