Salem witch trials

|

|

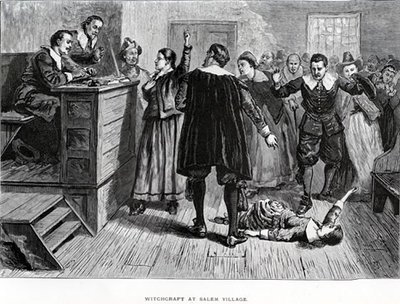

The Salem witch trials of Colonial America resulted in a number of convictions and executions for witchcraft in 1692 in Massachusetts, the result of a period of factional infighting and Puritan paranoia which led to the deaths of at least 25 people and the imprisonment of scores more. Witch trials were held in Europe several hundred years before those in Salem.

In 1692, in Salem Village (now Danvers, Massachusetts), a number of young girls, particularly Abigail Williams, Ann Putnam, Betty Parris and Mary Walcott, accused other townsfolk of magically possessing them, and therefore of being witches or warlocks in league with Satan.

The community, under threat from Indians and without any formal colonial government following the 1684 revocation of the Bay Colony charter and the 1689 revolt against Governor Andros, believed the accusations, and sentenced these people to either confess they were witches or be hanged. The accusations spread quickly, and within only a couple of months involved the neighboring communities of Andover, Amesbury, Salisbury, Haverhill, Topsfield, Ipswich, Rowley, Gloucester, Manchester, Malden, Charlestown, Billerica, Beverly, Reading, Woburn, Lynn, Marblehead, and Boston.

| Contents |

The beginning

In the cold winter of 1691-2, Betty Parris and Abigail Williams, respectively the daughter and the ward of the Reverend Samuel Parris, began to act peculiarly — speaking oddly, hiding under things and creeping on the floor. Not a single doctor the Rev. Mr. Parris brought forth could tell what ailed the girls, and at last one concluded that it was the hand of the Devil on them; in other words, they were possessed. Parris and other upstanding citizens began urging Betty and Abigail, and then newly possessed children Ann Putnam, Betty Hubbard, Mercy Lewis, Susannah Sheldon, Mercy Short, and Mary Warren, to name those who afflicted them. At last the girls began to blurt out names.

The first three women to be accused were Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba. Good, orphaned as a teenager at the death of her mother, a French innkeeper, was the town beggar, noted for her strange "muttering." Osborne was a bedridden elderly woman who had gotten on the wrong side of the Putnams when she cheated her first husband's children out of their inheritance, giving it to her new husband. Tituba was the Carib Native American slave of Samuel Parris; though she is very often referred to as black in modern historical and fictional interpretations of the trials, there is no evidence that she was anything but Native American.

These women were charged with witchcraft on March 1 and put in prison. Other accusations followed: Dorcas Good (four-year-old daughter of Sarah Good), Rebecca Nurse (a bedridden grandmother of saintly disposition), Abigail Hobbs, Deliverance Hobbs, Martha Corey, and Elizabeth and John Proctor. As the number of accusations grew, the jail populations of Salem, Boston, and surrounding areas swelled, and a new problem surfaced: Without a legitimate form of government, there was no way to try these women. None of them were tried until late May, when Governor Phips arrived and instituted a Court of Oyer and Terminer (to "hear and determine"). By then, Sarah Osborne had died in jail without a trial, as had Sarah Good's newborn baby girl, and many others were ill; there were perhaps 80 people in jail awaiting trial.

Over the summer, the Court heard cases approximately once per month, at mid-month. Of the accused, only one was released when the girls recanted their identification of him. All cases that were heard ended with the accused being condemned to death for witchcraft; no one was found innocent. Only those who pleaded guilty to witchcraft and supplied other names to the court were spared execution. Elizabeth Proctor and at least one other woman were given respite "for the belly," because they were pregnant. Though convicted, they would not be hanged until they had given birth. A series of four executions over the summer saw nineteen people hanged, including a respected minister, a former constable who refused to arrest more accused witches, and at least three people of some wealth. Six of the nineteen were men; most of the rest were impoverished women beyond childbearing age.

Only one execution was not by hanging. Giles Corey, an 80-year-old farmer from the southeast end of Salem, refused to enter a plea. The law provided for the application of a form of torture called peine fort et dure, in which the victim was slowly crushed by piling stones on him; after three days of excruciating pain, Corey died without entering a plea. Though his refusal to plead is often explained as a way of preventing his possessions from being confiscated by the state, this is not true; the possessions of convicted witches were often confiscated, and possessions of persons accused but not convicted were confiscated before a trial, as in the case of Corey's neighbor John Proctor and the wealthy English's of Salem Town. Some historians hypothesize that his personal character, a stubborn and lawsuit-prone old man who knew he was going to be convicted regardless, led to his recalcitrance.

The land suffered along with the people. Crops went untended, cattle uncared for. Often, accused people who had not yet been arrested gathered up their most portable belongings and fled to New York or beyond. Sawmills, their owners missing or distracted, their workers arrested or gawking at the spectacles at the jails or in the meetinghouses, sat idle. Commerce ground to, if not a halt, at least a snail's pace. And there was news of further Indian unrest to the west.

The ending

The witch trials ended in January 1693, although people already jailed for witchcraft were not all released until the next spring. Officially, the royal appointed governor of Massachusetts, Sir William Phips, ended them after an appeal by Boston-area clergy headed by Increase Mather, "Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits," published October 3, 1692. In it, Increase Mather stated "It were better that Ten Suspected Witches should escape, than that the Innocent Person should be Condemned." Echoes of this phrase can be found in the United States of America's innocent-until-proven-guilty judicial system of today.1

This incident was so profound that it helped end the influence of the Puritan faith on the governing of New England and led indirectly to the founding principles of the United States of America.

Participants

Clerical participants and commentators

- The Rev. Cotton Mather

- The Rev. Samuel Parris

- The Rev. Increase Mather

- The Rev. Francis Dane

- The Rev. Deodat Lawson

- The Rev. Samuel Willard

- The Rev. John Hale

Presiding officials

Presiding officials, Court of Oyer and Terminer

- Lieutenant Governor William Stoughton, Chief Magistrate

- Captain Jonathan Walcott

- Sheriff John Walcott

Associate Magistrates

- John Hathorne

- Samuel Sewall

- Thomas Danforth

- Bartholomew Gedney

- John Richards

- Nathaniel Saltonstall

- Peter Sargent

- Stephen Sewall, Clerk

- Wait Still Winthrop

Afflicted

Those who complained of bewitchment:

- Sarah Bibber

- Elizabeth Booth

- Sarah Churchill

- Martha Goodwin

- Elizabeth Hubbard

- Mary Lacey (also an accused witch)

- Mercy Lewis

- Elizabeth "Betty" Parris

- Bethshaa Pope

- Ann Putnam, Jr.

- Susanna Sheldon

- Mercy Short

- Martha Sprague

- Mary Walcott

- Mary Warren (was accused of witchcraft when she recanted and said the girls "did but dissemble", i.e. "were just faking it")

- Abigail Williams

Accused

This is not a complete list; there were anywhere from 150 to 300 accused recorded, and there may have been many more not imprisoned:

- Capt. John Alden Jr.

- Daniel Andrew

- Sarah Bassett

- Edward Bishop

- Sarah Bishop

- Mary Black

- Dudley Bradstreet

- John Bradstreet

- Sarah Buckley

- Richard Carrier

- Candy, a slave from Salem

- Mary Clarke

- Sarah Easty Cloyce

- Sarah Cole

- Giles Corey

- Mary Bassett DeRich

- Ann Dolliver

- Rebecca Eames

- Mary English

- Philip English

- Abigail Faulkner

- Ann Foster

- Dorcas Hoar

- Abigail Hobbs

- Deliverance Hobbs

- Elizabeth Howe

- Mary Ireson

- George Jacobs, Jr.

- Margaret Jacobs

- Elizabeth Johnson

- Mary Lacey, Sr.

- Mary Lacey (also an afflicted child)

- Sarah Osborne

- Lady Phips, wife of Governor Phips

- Susannah Post

- Elizabeth Bassett Proctor

- Mary (Woodrow) Sibley, wife of Samuel Sibley

- Tituba and her husband John Indian

- Job Tookey

- Hezekiah Usher

- Mary Withridge

Executed

- Bridget Bishop — hanged June 10, 1692

- The Rev. George Burroughs — hanged August 19, 1692

- Martha Carrier — hanged August 19, 1692

- Martha Corey — hanged September 22, 1692

- Giles Corey — pressed to death September 19, 1692

- Mary Easty — hanged September 22, 1692

- Sarah Good — hanged June 19, 1692

- Elizabeth Howe — hanged June 19, 1692

- George Jacobs, Sr. — hanged August 19, 1692

- Susannah Martin — hanged June 19, 1692

- Rebecca Nurse — hanged June 19, 1692

- Alice Parker — hanged September 22, 1692

- Mary Parker — hanged September 22, 1692

- John Proctor — hanged August 19, 1692

- Ann Pudeator — hanged September 22, 1692

- Wilmott Redd — hanged September 22, 1692

- Margaret Scott — hanged September 22, 1692

- Samuel Wardwell — hanged September 22, 1692

- Sarah Wildes — hanged June 19, 1692

- John Willard — hanged August 19, 1692

Died in jail

- Sarah Osborne

- "Dr." Roger Toothaker

- Ann Foster

- Lydia Dustin

- Dorcas Good (daughter of Sarah Good)

Note

1Increase Mather is frequently misquoted as saying it is better that "a hundred guilty witches go free": what he actually wrote, however, was "Ten Suspected Witches".

References

- Marc Aronson, Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials, Simon and Schuster, November, 2003, hardcover, 272 pages, ISBN 0689848641; large-print, Thorndike Press, April, 2004, hardcover, 324 pages, ISBN 078626442X

- Boyer, Paul & Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft, MJF Books, 1974.

- Starkey, Marion L., The Devil in Massachusetts, Alfred A. Knopf, 1949.

- Miller, Arthur, The Crucible — a play which implicitly compares McCarthyism to a witch-hunt

- Norton, Mary Beth, In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, Knopf, 2002

- Roach, Marilynne K.,The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-To-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege, Cooper Square Press, 2002.

See also

External links

- Salem Witch Trials and The Crucible (http://annettelamb.com/42explore/salemwitch.htm)

- A documentary archive (http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/salem/witchcraft/) including original court papers on the trials, maps, interactive maps, biographies, and internal and external links to more resources.

- Massachusetts Historical Society, Salem Witch Trials original document images (http://etext.virginia.edu/salem/witchcraft/archives/MassHist/)

- Salem Witch Trials (http://www.salemwitchtrials.com) includes lists of the afflicted, accused, and victims. Also has trial transcripts, biographies, and a message board.