Blue Whale

|

|

| Blue Whale Conservation status: Endangered | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing image Bluewhale877.jpg The world's largest animal | ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||||

| Balaenoptera musculus (Linneus, 1758) | ||||||||||||||||||

Blue Whale range |

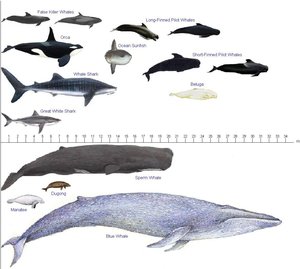

The Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is a marine mammal belonging to the suborder of baleen whales. Blue Whales are believed to be the largest animal ever to have lived, at up to 30 metres (100 feet) in length and 140 tonnes (150 short tons) or more in weight.

Blue Whales were abundant in most oceans around the world up until the beginning of the 20th century. For the first 40 years of that century they were hunted by whalers almost to extinction. Hunting of the species was outlawed by the international community in 1966. The current world population is between three and four thousand individuals, which are located in four (or possibly five) groups, the largest of which is in the North-East Pacific. There are two groups in the North Atlantic and one in Antarctic waters. Blue Whales found in the Indian Ocean may or may not be part of the Antarctic group.

| Contents |

Taxonomy and evolution

The Blue Whale is one of seven species of whale in the genus Balaenoptera. DNA sequencing analysis, however, shows that Blue Whales are phylogenetically closer to the Humpback and Gray Whales than other species in its genus. There have been at least 11 documented cases of Blue/Fin Whale hybrid adults in the wild. Aranson and Gullberg (1983) describe the genetic distance between a Blue and a Fin as about the same as that between a human and gorilla. The Balaenoptiidae family is believed to have diverged away from the other families of the Mysticetes suborder as long ago as the middle Oligocene. However, it is not known when the members of these families diverged from each other.

Rorqual_phylogenetic_tree.PNG

Some authorities classify the species into three subspecies: B. m. musculus, consisting of the north Atlantic and north Pacific populations, B. m. intermedia, the Southern Ocean population and B. m. brevicauda (also known as the Pygmy Blue Whale) found in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific. Some older authorities also list B. m. indica as a further separate subspecies in the Indian Ocean. Unlike the other three subspecies however, this last designation does not have a listing in the Red List of Threatened Species. Both subdivisions are still questioned by some scientists; genetic analysis may yet show there are just two true subspecies..

The specific name musculus is Latin and could mean "muscular", but it can also be interpreted as "little mouse". Linnaeus, who named the species in his seminal work of 1758, would have known this and, given his sense of humour, may have intended the ironic double meaning. Other common names for the Blue Whale have included the Sulphur-bottom, Sibbald's Rorqual, the Great Blue Whale and the Great Northern Rorqual. These names have fallen into disuse in recent decades.

Physical description

The Blue Whale has a long tapering body that appears stretched in comparison with the much stockier appearance of other whales. The head is flat and U-shaped and has a very prominent ridge running from the blow hole to the top of the upper lips. The front part of the mouth is thick with baleen plates; around 300 plates (each one metre long) hang from the upper jaw, running half a metre back into the mouth. Between 60 and 90 grooves (called ventral pleats) run along the throat parallel to the body. These pleats assist with evacuating water from the mouth after lunge feeding (see feeding below).

The dorsal fin is small, visible only briefly during the dive sequence. It varies in shape from one individual to another; some only have a barely perceptible lump, whilst other fins are quite prominent and falcate. It is located around three-quarters of the way along the length of the body. When surfacing to breathe, the Blue Whale raises its shoulder and blow hole region out of the water to a greater extent than other large whales (such as the Fin or Sei). This can often be a useful clue to identifying a species at sea. Whilst breathing, the whale emits a spectacular vertical single column blow (up to 12 m, typically 9 m) that can be seen from several kilometres on a calm day. Its lung capacity is 5,000 litres.

The flippers are three to four metres long. The upper side is gray with a thin white border. The lower side is white. The head and tail flippers are generally uniformly grey coloured. The back, and sometimes the flippers, however are usually mottled. The degree of mottling varies substantially from individual to individual. Some may have a uniform gray colour all over, whilst others demonstrate a considerable variation of dark blues, grays and blacks all tightly mottled.

Blue Whales can reach speeds of 50 km/h (30 mph) over short bursts, usually when interacting with other whales, but 20 km/h (12 mph) is a more typical travelling speed. When feeding they slow down to 5 km/h (3 mph). Some Blues in the North Atlantic and North Pacific raise their tail fluke when diving. The majority, however, do not.

Blue Whales most commonly live alone or with one other individual. It is not known whether those that travel in pairs stay together over many years or form more loose relationships. In areas of very high food concentration, as many as 50 Blue Whales have been seen scattered over a fairly small area. However, they do not form large close-knit groups as seen in other baleen species.

Size

The Blue Whale is believed to be the largest animal ever to have lived on Earth. The largest creature known from the dinosaur era is the Argentinosaurus of the Mesozoic era, which is estimated to have weighed up to 90 tonnes (100 short tons). There is some uncertainty as to the biggest Blue Whale ever found. Most data comes from Blue Whales killed in Antarctic waters during the first half of the twentieth century and was collected by whalers not well-versed in standard zoological measurement techniques. The longest whales ever recorded were two females measuring 33.6 m and 33.3 m (110 ft 3 in and 109 ft 3 in) respectively. There are some disputes over the reliability of these measurements, however; the longest whale measured by scientists at the American National Marine Mammal Laboratory (NMML) was 29.9 m long (98 ft) — about the same length as a Boeing 737 aeroplane or three double-decker buses.

A Blue Whale's head is so wide that 50 humans would be able to stand on its tongue. Its heart is close to the size of a small car. A human baby could crawl through a Blue Whale's arteries. A newborn Blue Whale calf weighs more than an adult elephant. During the first 7 months of its life, a baby Blue Whale drinks approximately 400 litres (100 U.S. gallons) of milk every day. Baby Blue Whales also gain weight quickly: 90 kg (200 pounds) every 24 hours.

Blue Whales are very difficult to weigh on account of their massive size. Most Blue Whales killed by whalers were not weighed as a whole, but cut up into manageable pieces before being weighed. This caused an underestimate of the total weight of the whale, due to loss of blood and other fluids. Even so, measurements between 150 to 170 tonnes (160 and 190 short tons) were recorded of animals up to 27 m (88 ft 6 in) in length. The weight of a 30 m (98 ft) individual is believed by the NMML to be in excess of 180 tonnes (200 short tons). The largest Blue Whale accurately weighed by NMML scientists to date was a female that weighed 177 tonnes (196 short tons).

Feeding

Blue Whales feed exclusively on krill. The exact species of this zooplankton eaten by Blue Whales varies from ocean to ocean. In the North Atlantic Meganyctiphanes norvegica, Thysanoessa raschii, Thysanoessa inermis and Thysanoessa longicaudata are the usual food. In the North Pacific Euphausia pacficia, Thysanoessa inermis, Thysanoessa longipes, Thysanoessa spinifera and Nyctiphanes symplex; in the Antarctic Euphausia superba, Euphausia crystallorophias and Euphausia vallentni.

The whales always feed on the highest concentration of krill that they can find. This means that they typically feed at depth (more than 100 m) during the daytimes, and only surface feed at night. Dive times are typically ten minutes when feeding. Diving for twenty minutes is quite common. The longest recorded is thirty-six minutes (Sears 1998). The whale feeds by lunging forward at groups of krills, taking the animals and a large quantity of water into the mouth at once. The water is then squeezed out through the baleen plates by pressing the ventral pouch and tongue up against the water. Once the mouth is clear of water, the remaining krill, unable to pass through the plates, are swallowed.

Life cycle

Mating starts in the latter part of the autumn, and continues to the end of winter. Little is known about mating behaviour or even breeding grounds. Females typically give birth at the start of the winter once every two to three years after a gestation period of ten to twelve months. The calf weighs about two and a half tonnes and is around 7 m in length. Weaning takes place after about six months, by which time the calf has doubled in length. Sexual maturity is typically reached at eight to ten years by which time males are at least 20 m long (or more in the southern hemisphere). Females are larger still, reaching sexual maturity around 21 m or around the age of five.

Scientists estimate that Blue Whales can live for at least eighty years; however, since individual records do not date back into the whaling era, this will not be known with certainty for many years yet. The longest recorded study of a single individual is thirty-four years, in the northeast Pacific (reported in Sears, 1998). The whales' only natural predator is the Orca. Calambokidis et al (1990) report that as many as 25% of mature Blue Whales have scars resulting from Orca attack. The rate of mortality due to such attacks is unknown.

Blue Whale strandings are extremely uncommon and, because of the species' social structure, mass strandings are unheard of. However when strandings do occur they can become quite a public event. In 1920, a Blue Whale washed up on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It had been shot in the head by whalers, but the harpoon had failed to explode. As with other mammals, the fundamental instinct of the whale was to try to carry on breathing at all costs, even though this meant beaching to prevent itself from drowning. Two of the whale's bones erected just off a main road on Lewis remain a tourist attraction.

Vocalisations

See also: Whale song

The Blue Whale is the loudest animal in the world. Estimates made by Cummings and Thompson (1971) and Richardson et al (1995) suggest that source level of sounds made by Blue Whales are between 155 and 188 decibels when measured at a reference pressure of one micro pascal at one metre. Even accounting for different impedances between water and air and different standard reference pressures, an equivalent sound range in air is 89-122 decibels.Template:Ref By comparison a pneumatic drill is about 100dB loud. A human however, would likely not perceive the Blue Whale as the loudest of all animals. All Blue Whale groups make calls at a fundamental frequency of between 10 and 40 Hz, and the lowest frequency sound a human can typically perceive is 20 Hz. Blue Whale calls last between ten and thirty seconds. Additionally Blue Whales off the coast of Sri Lanka have been recorded repeatedly making "songs" of four notes duration lasting about two minutes each, reminiscent of the well-known Humpback Whale songs. Researchers believe that as this phenomenon has not been seen in any other populations, it may be unique to the B. m. brevicauda (Pygmy) subspecies.

Scientists do not know why Blue Whales vocalise. Richardson et al (1995) discuss six possible reasons:

- Maintenance of inter-individual distance

- Species and individual recognition,

- Contextual information transmission (e.g., feeding, alarm, courtship)

- Maintenance of social organization (e.g., contact calls between females and males)

- Location of topographic features

- Location of prey resources

(List adapted from National Marine Fisheries Service Biological Opinion paper, 2002)

Population and whaling

The hunting era

Blue Whales are not easy to catch, kill, or retain. Their speed and power meant that they were often not the target of early whalers who instead targeted Sperm and Right Whales. As the populations of these species declined, whalers increasingly hunted the largest baleen whales, including the Blue Whale. In 1864 Norwegian Svend Foyn equipped a steamboat with harpoons specifically designed for catching large whales. Although initially troublesome, the method caught on, and by the end of the nineteenth century the population of Blue Whales in the North Atlantic had diminished.

Hunting of Blue Whales rapidly increased around the world, and by 1925, the United States, Britain and Japan had joined Norway in chasing whales on 'catcher boats' that caught the whales and handed them onto huge 'factory ships' for processing. In 1930, forty-one ships killed 28,325 Blue Whales. By the end of World War II populations had been significantly depleted, and in 1946 the first quotas restricting international trade in whales were introduced. These were ineffective because of the lack of differentiation between species. Rare species could be hunted equally with those found in relative abundance. By the time Blue Whale hunting was finally banned in the 1960s by the International Whaling Commission, 350,000 Blue Whales had been killed and the world population had been reduced to less than 1% of its total one hundred years before.

Population and distribution today

Since the whaling ban, the global Blue Whale population is believed to have remained more or less constant, ranging between 3,000 to 4,000 individuals. The Blue Whale remains listed as "endangered" on the Red List of threatened species as it has been since the list's inception. The largest concentration, consisting of about 2,000 individuals, is the North-east Pacific population that ranges from Alaska to Costa Rica but is most commonly seen from California in summer. This group represents the best hope for a long-term recovery in Blue Whale population. Sometimes this population strays over to the North-West Pacific; infrequent sightings between Kamchatka and the northern tip of Japan have been recorded.

Population estimates for the Southern Ocean population range from 750 to 1200. The migratory pattern of this stock is not well understood. It may or may not be a group distinct from the Indian Ocean population of unknown number that is sometimes spotted off the northeast coast of Sri Lanka. Some members of the Southern Ocean group approach the eastern South Pacific coast. In Chile, the Cetacean Conservation Center, with support from the Chilean Navy, is undertaking extensive research and conservation work on a recently discovered feeding aggregation of the species off the coast of Chiloe Island.

In the North Atlantic two stocks are recognised. The first is found off Greenland, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. This group is estimated to total about 500 in number. The second, more easterly group, is spotted from the Azores in Spring and Iceland in July and August; it is presumed that the whales follow the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between the two volcanic islands. Beyond Iceland, Blue Whales have been spotted as far north as Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen though such sightings are rare. Scientists do not know where these whales spend their winters. The total North Atlantic population is between 600 and 1500 in number.

Human threats to the potential recovery of Blue Whale populations include the accumulation of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) chemicals within the whale's blood, causing poisoning and premature death, and the ever-increasing amount of noise created by ocean traffic. This noise drowns out the noises produced by whales (see whale song), which may make it harder for whales to find a mate.

Media

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

References

- Richard Sears (1998). "Blue Whale" pp 112-116 in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen eds).

- William Perrin and Joseph Geraci. "Stranding" pp 1192-1197 in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Perrin, Wursig and Thewissen eds).

- Template:RefAudubonMarineMammals pp 89-93

- Template:Journal reference

- Template:Book reference

- Template:Book reference

- Template:Journal reference

- Template:Journal reference

- National Marine Fisheries Service (2002). "Endangered Species Act - Section 7 Consultation Biological Opinion". Published online at (PDF format) (http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/prot_res/readingrm/ESAsec7/7pr_surtass-2020529.pdf)

- Template:Web reference

- Template:Web reference

Pictures of Animals

- Classroom Clipart Pictures and Photos of Animals (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=Animals)

Animal Clipart

- Animal Clipart (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=Clipart/Animals)

External links

- Chilean Conservation Centre (http://www.ccc-chile.org)

- Science seeks clues to pygmy whale (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/3003564.stm)

- Blue Whale photographs (http://www.earthwindow.com/blue.html) by Mike Johnson, Marine Natural History Photographer

- American Cetacean Society Blue Whale fact sheet (http://www.acsonline.org/factpack/bluewhl.htm)

- Information on Blue Whales (http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/whales/species/Bluewhale.shtml) from EnchantedLearning.com

- Numerous Blue Whale photographs (http://www.oceanlight.com/html/blue_whale.html) from OceanLight.com

- Blue Whale Species profile (http://seamap.env.duke.edu/species/tsn/180528) at OBIS-SEAMAP: mapping marine mammals, birds and turtles (http://seamap.env.duke.edu)

- MarineBio: Blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus (http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=41)