Oscar Wilde

|

|

Oscar.jpg

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (October 16, 1854 – November 30, 1900) was an Anglo-Irish playwright, novelist, poet, and short story writer. One of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London, and one of the greatest celebrities of his day, known for his barbed and clever wit, he suffered a dramatic downfall and was imprisoned after being convicted in a famous trial of "gross indecency" for his homosexuality.

| Contents |

Biography

Birth and early life

Wilde was born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin, to Sir William Wilde and his wife Jane, herself a successful writer and an Irish nationalist. Sir William, Ireland's leading ear and eye surgeon, wrote books on archaeology and folklore. He was a renowned philanthropist, and his dispensary for the care of the city's poor, situated in Lincoln Place at the rear of Trinity College, Dublin was the forerunner of the Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital, now located at Adelaide Road.

Oscar_wilde_in_dublin.jpg

In June 1855, the family moved to 1 Merrion Square, a fashionable residential area. Here, Lady Wilde held a regular Saturday afternoon salon with guests including such figures as Sheridan le Fanu, Samuel Lever, George Petrie, Isaac Butt and Samuel Ferguson. Oscar was educated at home up to the age of nine. He attended Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, Fermanagh from 1864 to 1871, spending the summer months with his family in rural Waterford, Wexford and at William Wilde's family home in Mayo. Here the Wilde brothers played with the young George Moore.

After leaving Portora, Oscar studied the classics at Trinity College, Dublin, from 1871 to 1874. He was an outstanding student, and won the Berkeley Gold Medal, the highest award available to classics students at Trinity. He was granted a scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he continued his studies from 1874 to 1878. While at Magdalen, Wilde won the 1878 Oxford Newdigate Prize for his poem Ravenna. He graduated with a double first.

Marriage and family

After graduating from Magdalen, Wilde returned to Dublin, where he met and fell in love with Florence Balcome. She in turn became engaged to Bram Stoker. On hearing of her engagement, Wilde wrote to her stating his intention to leave Ireland permanently. He left in 1878 and was to return to his native country only twice, for brief visits. The next six years were spent in London, Paris and the United States, where he travelled to deliver lectures.

In London, he met Constance Lloyd, daughter of the wealthy QC, Horace Lloyd. She was visiting Dublin in 1884 when Oscar was in the city to give lectures at the Gaiety Theatre. He proposed to her and they married on May 29, 1884 in Paddington, London. Constance's allowance of £250 allowed the Wildes to live in relative luxury. The couple had two sons, Cyril (1885) and Vyvyan (1886). After Oscar's downfall Constance took the surname Holland for herself and the boys. She died in 1898 following spinal surgery and was buried in Staglieno Cemetery in Genoa, Italy. Cyril was killed in France in World War I. Vyvyan survived the war and went on to become an author and translator. He published his memoir in 1954. His son, Merlin Holland, has edited and published several works about his grandfather in the last decade.

Aestheticism

Wasp_cartoon_on_Oscar_Wilde.jpg

His behaviour cost him a dunking in the River Cherwell in addition to having his rooms trashed, but the cult spread among certain segments of society to such an extent that languishing attitudes, "too-too" costumes and Aestheticism generally became a recognised pose. Aestheticism was caricatured in Gilbert and Sullivan's mocking operetta Patience (1881).

Wilde was deeply impressed by the English writers John Ruskin and Walter Pater, who argued for the central importance of art in life. He later commented ironically on this view when he wrote, in The Picture of Dorian Gray, "All art is quite useless". This quote also reflects Wilde's support of the aesthetic movement's basic principle: Art for art's sake. This doctrine was coined by the philosopher Victor Cousin, promoted by Theophile Gautier and brought into prominence by James McNeill Whistler.

The aesthetic movement, represented by the school of William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had a permanent influence on English decorative art. As the leading aesthete, Oscar Wilde became one of the most prominent personalities of his day. Though he was ridiculed for them, his paradoxes and witty sayings were quoted on all sides.

In 1879 Wilde started to teach Aesthetic values in London. In 1882 he went on a lecture tour in the United States and Canada. He was torn apart by no small number of critics — The Wasp, a San Francisco newspaper, published a cartoon ridiculing Wilde and Aestheticism — but also was surprisingly well-received in such rough-and-tumble settings as the mining town of Leadville, Colorado. [1] (http://www.todayinliterature.com/stories.asp?Event_Date=12/24/1881) On his return to the United Kingdom, he worked as a reviewer for the Pall Mall Gazette in the years 1887-1889. Afterwards he became the editor of Woman's World.

Literary works

He had already published in 1881 a selection of his poems, which, however, attracted admiration in only a limited circle. His most famous fairy tale, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, appeared in 1888, illustrated by Walter Crane and Jacob Hood. This volume was followed up later by a second collection of fairy tales, The House of Pomegranates (1892), acknowledged by the author to be "intended neither for the British child nor the British public."

His only novel The Picture of Dorian Gray was published in 1891. Critics have often claimed that there existed parallels between Wilde's and the protagonist's life, and it was used as evidence against him at his trial. Wilde contributed some feature articles to the art reviews, and in 1891 re-published three of them as a book called Intentions.

Wilde's favourite genres were the society comedy and the play. From 1892 on, almost every year a new work of Oscar Wilde was published. His first real success with the larger public was as a dramatist with Lady Windermere's Fan at the St James's Theatre in 1892, followed by A Woman of No Importance (1893), An Ideal Husband (1895) and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), which became Wilde's masterpiece in which he satirised the upper class.

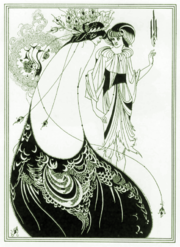

The dramatic and literary ability shown in these plays, all of which were published later in book form, was as undisputed as their action and ideas were characteristically paradoxical. In 1892 the Lord Chamberlain who also was the licensor of plays for the British government refused a license for Salomé to be performed owing to a law forbidding the depiction of Biblical characters onstage. It was produced in Paris by Sarah Bernhardt in 1894. This play formed the basis for one of Richard Strauss' early operas (Salome, 1905).

Wilde's sexuality

Robert_Ross_at_24.jpg

Wilde's sexual orientation has variously been considered bisexual or gay, depending on how the terms are defined. His inclination towards relations with younger men was relatively well-known, the first such relationship having probably been with Robert Ross, who proved his most faithful friend and would be his literary executor. Ross, a boy of seventeen when Wilde met him, was already aware of Wilde's poems and indeed had been beaten for reading them. By Richard Ellman's account, Ross, ". . . so young and yet so knowing, was determined to seduce [Wilde]." Later, Ross boasted to Lord Alfred Douglas that he was "the first boy Oscar ever had" and there seems to have been much jealousy between them.

In his writings, an early indication of Wilde's sexuality is found in The Portrait of Mr. W. H. (1889), in which he propounds a theory that Shakespeare’s sonnets were written out of the poet's love of a young man.

Homosexualitywilde.jpg

In 1891, Wilde became intimate with Lord Alfred Douglas, who went by the nickname "Bosie". Bosie's father, John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry, became increasingly enraged at his son's involvement with Wilde. He confronted the two publicly several times, and although each time Wilde was able to mollify the elder Douglas, eventually the Marquess threw down the gauntlet. He planned to interrupt the opening night of Wilde's play The Importance of Being Earnest in February 1895 with an insulting delivery of vegetables, but somebody tipped Wilde off and the Marquess was barred from entering the theatre. On February 18, 1895, the Marquess publicly insulted Wilde with a misspelt note (actually a calling card) left at Wilde's club, the Albemarle. The note read "For Oscar Wilde posing as a Somdomite" (that is, a sodomite).

The Queensberry scandal

Although Wilde's friends advised him to ignore the insult, Lord Alfred later admitted that he egged Wilde on to charge Queensberry with criminal libel. Queensberry was arrested, and in April 1895, the crown took over the prosecution of the libel case against the Marquess. The trial lasted three days. The prosecuting counsel, Edward Clarke, was unaware that Wilde had had liaisons and romantic relationships with other men. Clarke asked Wilde directly whether there was any substance to Douglas's accusations and Wilde denied that there was. Edward Carson, the barrister who defended Douglas, hired investigators who were able to locate a number of men with whom Wilde had been involved, either socially or sexually.

Wilde put on a tremendous display of drama in the first day of the trial, parrying Carson's cross-examination with witticisms and sarcasm, often breaking the courtroom up with laughter. For instance, Carson asked Wilde whether he had ever adored any man younger than himself, and Wilde quipped, "I have never given adoration to anybody except myself."

However, when Clarke found that Wilde had deceived him, he recommended that Wilde withdraw the prosecution, and the case was dismissed. Based on the evidence that Carson had uncovered, Wilde was charged with "committing acts of gross indecency with other male persons" under Section 11 of the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, this being little more than a euphemism for any sex between males. He was arrested on April 6, 1895.

Trial and Imprisonment in Reading jail

At his own trial Wilde dropped any semblance of subterfuge and delivered an impassioned defense of male love in answer to the cross examination by Mr. C. F. Gill:

- Gill: What is "the love that dares not speak its name?"

- Wilde: "The love that dares not speak its name" in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art, like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as "The love that dares not speak its name," and on that account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an older and a younger man, when the older man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so, the world does not understand. The world mocks at it, and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.

Wilde was convicted on May 25, 1895 of gross indecency and sentenced to serve two years hard labour. He was imprisoned first at Pentonville and then at Wandsworth prison in London, and finally transferred in November to Reading, a town some 30 miles west of London. At first he wasn't even allowed paper and pen to write. During his time in prison, Wilde wrote a 50,000 word letter to Douglas, which he was not allowed to send while still a prisoner, but which he was allowed to take with him at the end of his sentence. On his release he gave the manuscript to Ross, who may or may not have carried out Wilde's instructions to send a copy to Douglas who, in turn, denied having received it. Ross published a much expurgated version of the letter (about 30% only) in 1905 (4 years after Wilde's death) with the title De Profundis, expanded it slightly for an edition of Wilde's collected works in 1908 and then donated it to the British Museum on the understanding that it would not be made public until 1960. In 1949 Wilde's son Vyvyan Holland published it again, including parts formerly omitted, but relying on a faulty typescript bequeathed to him by Ross. Its first complete and correct publication did not take place until 1962 in The Letters of Oscar Wilde.

The manuscripts of A Florentine Tragedy and an essay on Shakespeare's sonnets were stolen from his house in 1895. In 1904 a five-act tragedy, The Duchess of Padua, written by Wilde about 1883 for Mary Anderson, but not acted by her, was published in a German translation (Die Herzogin von Padua, translated by Max Meyerfeld) in Berlin.

After his release

Wildgrve.JPG

On his deathbed he converted to the Roman Catholic church, which he had long admired. He spent his last days in Hotel d’Alsace in Paris. He is reported to have said shortly before his death, "My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has got to go."

Wilde died of cerebral meningitis on November 30, 1900. Different opinions are given on the cause of the meningitis; Richard Ellmann claimed it was syphilitic; Merlin Holland, Wilde's grandson, thought this to be a misconception, noting that Wilde's meningitis followed a surgical intervention, perhaps a mastoidectomy; Wilde's physicians, Dr. Paul Cleiss and A'Court Tucker reported that the condition stemmed from an old suppuration of the right ear (une ancienne suppuration de l'oreille droite d'ailleurs en traitement depuis plusieurs années) and do not allude to syphilis. Most modern scholars and doctors agree that syphilis was unlikely to have been the cause of his death. Wilde was buried in the Cimetière de Bagneux outside Paris but was later moved to Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His tomb in the Père Lachaise was designed by the sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein.

Biographies

- After Wilde's death, Wilde's friend Frank Harris wrote a biography of Wilde: Oscar Wilde. His Life and Confessions.

- In 1954 Vyvyan Holland published his memoir Son of Oscar Wilde. It was revised and updated by Merlin Holland in 1999.

- In 1987 Richard Ellmann published Oscar Wilde, a very minute biography.

- In 1997 Merlin Holland published a book entitled The Wilde Album. This rather small volume seems to contain at least twice its size worth of pictures and other Wilde memorabilia, much of which had not been published before. It includes 27 pictures taken by the portrait photographer Napoleon Sarony, one of which graces the beginning of this article.

- 1999 saw the publication of Oscar Wilde on Stage and Screen written by Robert Tanitch. This book is a comprehensive record of Oscar's life and work as presented on stage and screen from 1880 until 1999. It includes cast lists and snippets of reviews.

- 2003 saw the publication of the first complete account of Wilde's sexual and emotional life in The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde by Neil McKenna (published by Century/Random House).

- A multiple-issue 'chapter' of Dave Sim's comic book Cerebus the Aardvark, entitled Melmoth, (later collected as a single volume under that title) retells the story of Wilde's final months with the names and places slightly altered to fit the world of the Cerebus storyline, while Cerebus himself spends most of the chapter as a passive observer.

Biographical Films, Television Series and Stage Plays

- Two films of his life were released in 1960. The first to make it to the theaters was Oscar Wilde starring Robert Morley. Then came The Trials of Oscar Wilde starring Peter Finch. At the time homosexuality was still punishable by a jail sentence in the UK and both films were rather cagey in touching on the subject without being explicit about it.

- In the summer of 1977 Vincent Price began performing in the one man play Diversions and Delights. Written by John Gay and directed by Joe Hardy the premise of the play is that an aging Oscar Wilde, to earn some much needed money, gave a lecture on his life in a Parisian Theater on November 28, 1899 (just a year before his death). The play was a success everywhere it was performed, except for its New York City run. It was revived in 1990 in London with Donald Sinden in the role.

- In 1978 London Weekend Television produced a television series about the life of Lillie Langtry entitled Lillie. In it Peter Egan played Oscar. The bulk of his scenes portrayed their close friendship up to and including their tours of America in 1882. Thereafter, he was in a few more scenes leading up to his trials in 1895.

- Michael Gambon portrayed Wilde on British Television in 1983 in the three part BBC series Oscar concentrating on the trial and following prison term.

- 1988 saw Nickolas Grace playing Wilde in Ken Russell's film Salome's Last Dance.

- A fuller look at his life, without any of the restrictions of the 1960 films, is Wilde (1997) starring Stephen Fry.

- Oscar: In October 2004, a stage musical by Mike Read about Oscar Wilde closed after just one night at the Shaw Theatre in Euston after a severe critical mauling.

Bibliography

Poetry

- Poems (1881)

- The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898)

Plays

- Vera, or The Nihilists (1880)

- The Duchess of Padua (1883)

- Salomé (French version) (1893, first performed in Paris 1896)

- Lady Windermere's Fan (1892)

- A Woman of No Importance (1893)

- Salomé: A Tragedy in One Act: Translated from the French of Oscar Wilde by Lord Alfred Douglas with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley (1894)

- An Ideal Husband (1895) [2] (http://wikisource.org/wiki/An_Ideal_Husband)

- The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) [3] (http://wikisource.org/wiki/The_Importance_of_Being_Earnest)

- La Sainte Courtisane and A Florentine Tragedy first published 1908 in Methuen's Collected Works

(Dates are dates of first performance, which approximate far better with the probable date of composition than dates of first publication.)

Prose

- The Canterville Ghost (1887)

- The Happy Prince and Other Stories (1888) [4] (http://www.gutenberg.net/dirs/etext97/hpaot10h.htm)

- The Portrait of Mr. W. H. (1889)

- Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime and other Stories (1891)

- Intentions (1891)

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891)

- House of Pomegranates (1891)

- The Soul of Man Under Socialism (First published in the Pall Mall Gazette, 1891, first book publication 1904)

- De Profundis (1905)

- The Letters of Oscar Wilde (1960) This was rereleased in 2000, with letters uncovered since 1960, and new, detailed, footnotes by Merlin Holland.

References

- Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. (Vintage, 1988) ISBN 0521479878

- Igoe, Vivien. A Literary Guide to Dublin. (Methuen, 1994) ISBN 0-4136912-0-9

- Raby, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Oscar Wilde. (CUP, 1997) ISBN 0521479878

- Wilde, Oscar. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. (Collins, 2003) ISBN 0007144369

Online

- Oscar Wilde at the Princess Grace Irish Library (http://www.pgil-eirdata.org/html/pgil_datasets/authors/w/Wilde,O/life.htm) Captured November 12, 2004.

- Oscar Wilde's brief biography and works (http://Wilde.thefreelibrary.com/)

- Dissertation about the relationship between "The Picture of Dorian Gray" and Postmodernism (http://oscarwilde.projectx2002.org)

- 10 most popular misconceptions about Oscar Wilde (http://books.guardian.co.uk/top10s/top10/0,6109,950928,00.html)

- King, Steve. "Wilde in America" (http://www.todayinliterature.com/stories.asp?Event_Date=12/24/1881) from Today in Literature, captured November 12, 2004.

External links

Template:Wikisource author Template:Wikiquote

- Mr. O.W. - Oscar Wilde (http://users.pandora.be/moonen/wilde/)

- Oscar Wilde - Standing Ovations (http://home.arcor.de/oscar.wilde/start.htm), a variety of resources including full texts.

- Selected Oscar Wilde Poems (http://poetry.poetryx.com/poets/131/)

- Statue of Oscar Wilde and Eduard Vilde (http://www.tartu.ee/?page_id=898&lang_id=2&plugin_pic_id=170) in Tartu (second largest city in Estonia)

Online texts:

- Collected Works (http://www.ucc.ie/celt/et19wilde.html)

- The Oscar Wilde Collection (http://www.oscarwildecollection.com)

- Online Books by Oscar Wilde (http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/search?amode=start&author=Wilde%2c%20Oscar)bg:Оскар Уайлд

cy:Oscar Wilde da:Oscar Wilde de:Oscar Wilde es:Oscar Wilde eo:Oscar WILDE fr:Oscar Wilde gl:Oscar Wilde it:Oscar Wilde he:אוסקר ויילד nl:Oscar Wilde ja:オスカー・ワイルド no:Oscar Wilde pl:Oscar Wilde pt:Oscar Wilde ro:Oscar Wilde fi:Oscar Wilde sv:Oscar Wilde tr:Oscar Wilde zh:奥斯卡·王尔德 ru:Уайльд, Оскар