Wright brothers

|

|

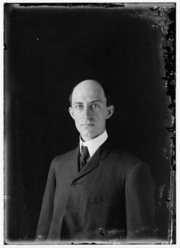

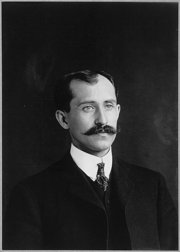

The Wright brothers, Orville Wright (August 19, 1871 - January 30, 1948) and Wilbur Wright (April 16, 1867 - May 30, 1912), are generally credited with the design and construction of the first practical aeroplane, and making the first controllable, powered heavier-than-air flight along with many other aviation milestones. However, their accomplishments have been subject to many counter-claims by some people and nations at their start, and through to the present day.

| Contents [hide] |

Early career and research

Wilbur Wright was born in Millville, Indiana in 1867, Orville in Dayton, Ohio in 1871. Both received high school educations but no diplomas.

The Wright brothers grew up in Dayton, Ohio, where they opened a bicycle repair, design and manufacturing company (the Wright Cycle Company) in 1892. They used the occupation to fund their growing interest in flight. Drawing on the work of Sir George Cayley, Octave Chanute, Otto Lilienthal and Samuel Pierpont Langley, they began their mechanical aeronautical experimentation in 1899. The brothers extended the technology of flight by emphasizing control of the aircraft (instead of increased power) for taking off into the air. They developed three-axis control and established principles of control still used today.

The Wrights had researched and initially relied upon the aeronautical literature of the day, including Lilienthal's tables; but finding that the Smeaton Coefficient (a variable in the formula for lift and the formula for drag) was wrong, had a wind tunnel built by their employee, Charlie Taylor, and tested over two hundred different wing shapes in it, eventually devising their own tables relating air pressure to wing shape. Their work and projects with bicycles, gears, bicycle motors, and balance (while riding a bicycle), were critical to their success in creating the mechanical airplane.

During their research, the Wrights always worked together, and their contributions to the aeroplane's development are inseparable.

Flights

The Wright Brothers were noted for placing the emphasis of their aviation research on navigational control rather than simply lift and propulsion which would make sustained flight practical. To that end, they first made gliders (beginning in 1899), using an intricate system called “wing warping.” If one wing bent one way, it would receive more lift, which would make the plane lift. If they could control how the gliders' wings warped, then it would make flying much easier. To allow warping in the first gliders, they had to keep the front and rear posts that hold up the glider unbraced. The warping was then controlled by wire running through the wings, which led to sticks the flyer held, and he could pull one or the other to make it turn left or right.

In 1900 they went to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina to continue their aeronautical work, choosing Kitty Hawk (specifically a sand dune called Kill Devil Hill) on the advice of a National Weather Service meterologist because of its strong and steady winds and because its remote location afforded the brothers privacy from prying eyes in the highly competitive race to invent a successful heavier-than-air flying machine. They experimented with gliders at Kitty Hawk from 1900 through 1902, each year constructing a new glider. Their last glider applied many important innovations in flight, and the brothers made over a thousand flights with it. On March 23, 1903 they applied for a patent (granted as U.S. patent number 821,393, "Flying-Machine", on May 23, 1906) for the novel technique of controlling lateral movement and turning by "wing warping". By 1903, the Wright Brothers were perhaps the most skilled glider pilots in the world.

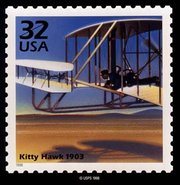

In 1903, they built the Wright Flyer -- later the Flyer I (today popularly known as the Kitty Hawk), carved propellers and had an engine built by Taylor in their bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio. The propellers had an 80% efficiency rate. The engine was superior to manufactured ones, having a low enough weight-to-power ratio to use on an aeroplane*.

Then on December 17, 1903, the Wrights took to the air, both of them twice. The first flight, by Orville, of 39 meters (120 feet) in 12 seconds, was recorded in a famous photograph. In the fourth flight of the same day, the only flight made that day which was actually controlled, Wilbur Wright flew 279 meters (852 ft) in 59 seconds. [1] (http://www.thewrightbrothers.org/fivefirstflights.html).

The flights were witnessed by 4 lifesavers and a boy from the village, making it arguably the first public flight. A local newspaper reported the event, inaccurately. Only one other newspaper, the Cincinnati Enquirer, printed the story the next day.

The Flyer I cost less than a thousand dollars to construct. It had a wingspan of 40 feet (12 m), weighed 750 pounds (340 kg), and sported a 12 horsepower (9 kW), 170 pound (77 kg) engine.

The Wrights established a flying field at Huffman Prairie, near Dayton, and continued work in 1904, building the Flyer II and using a catapult take-off system to compensate for the lack of wind in this location. By the end of the year, the Wright Brothers had sustained 105 flights, some of them of 5 minutes, circling over the prairie, which is now part of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. In 1905, they built an improved aeroplane, the Flyer III.

In 1904 and 1905, the Wright Brothers conducted over 105 flights from Huffman Prairie in Dayton, inviting the press and friends and neighbors. Here they completed the first aerial circle and by October 5, 1905 Wilbur set a record of over 39 minutes in the air and 24 1/2 miles, circling over Huffman Prairie.

When a large contingent of journalists arrived at the field in 1904, for instance, the Wrights were experiencing mechanical difficulties, and were unable to correct them within two days. As a result, the first local report of the flights appeared in a beekeeping magazine. The news was not widely known outside of Ohio, and was often met with skepticism. The Paris edition of the Herald Tribune headlined a 1906 article on the Wrights "FLYERS OR LIARS?"

The brothers became world famous in 1908 and 1909 when, weary of continuing doubt, they took their aeroplane on tour. Wilbur toured Europe demonstrating their aeroplane and organising a company to market it, while Orville demonstrated the flyer to the United States Army at Fort Myer, Virginia.

On May 14, 1908 the Wright Brothers made the first two-person aircraft flight with Charlie Furnas as a passenger. Thomas Selfridge became the first person killed in a powered airplane on September 17, 1908 when a propeller failure caused the crash of the passenger-carrying plane Orville was piloting during military tests at Fort Myer in Virginia. Orville broke a leg and two ribs. (This was the only serious accident the Wrights suffered.) In late 1908, Madame Hart O. Berg became the first woman to fly when she flew with Wilbur Wright in Le Mans, France.

The Wright Brothers brought great attention to flying by Wilbur's flight around the Statue of Liberty in New York in 1909.

Also in 1909, the Wrights won the first US military aviation contract when they built a machine that met the requirements of a two-seater, capable of flights of an hour's duration, at an average of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) and land undamaged. $30,000 of the federal budget was reserved for military aviation. That year the Wrights were also building Wright Flyers in factories in Dayton and in Germany.

On October 25, 1910, the Wright Brothers were engaged by Max Moorehouse of Columbus, Ohio to undertake the first commercial air cargo shipment. Moorehouse, owner of Moorehouse-Marten's Department store in Columbus asked if the Wright Brother's could carry a shipment of silk ribbon from a wholesaler in Dayton to Columbus. The Wright brothers agreed to the proposal, adding that their pilot and airplane would put on an exhibition once the cargo was delivered to the Driving Park landing area on the east side of Columbus. Moorehouse, in turn, agreed to pay the Wright's $5,000 for the service, which was more an exercise in advertising than a simple delivery. The actual flight occurred on November 7, 1910, with the Model "B" Wright Flyer piloted by Phil Parmalee. The sixty-two mile flight took 62 minutes, with Parmalee overtaking the "Big-Four" express train in London, Ohio. In addition to carrying the first air-freight, Parmalee's speed of 60 miles an hour set a world's record for in flight speed. For the return trip, however, the Wright Flyer was loaded on a train the night of the world record flight, and Paramalee returned to Dayton on the same Big Four Express train that he overtook in the air the day before.

The Wrights took over 300 photographs of flights and many other events of those pioneer days of aviation.

The Wrights were involved in several patent battles, which they won in 1914. Wilbur died from typhoid fever in 1912, an event Orville never completely recovered from. Orville sold his interests in the airplane company in 1915 and died thirty-three years later from a heart attack while fixing the doorbell to his home in Oakwood, Ohio. Neither brother married. The Flyer I is now on display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C..

- One neat and interesting fact about the motor is that the chain used was a bicycle chain, not surprisingly.

Earlier and later flying craft

There are many claims of earlier flights made by other flying machines in various categories and qualifications. See First flying machine.

Lighter than air balloons, dirigibles, airships had been taking people into the sky for much of the 18th century before the Wrights, and several people had been working on heavier than air flying machines as well. Numerous claims before the Wrights aspire to the title of being the first powered, controlled, and self-sustaining flight (or minor variations of this classification). Several claims are actually after the Wrights, and lay claim by discounting the Wrights attempt either on the basis of its authenticity (that it's valid enough) on some technical basis of the flyer in relation to the technical details to the title, or sometimes both. (Note that claims earlier than the Wrights are often criticized on similar grounds.)

The flights that took place have what is usually considered to be reasonable proof, including photos and multiple eyewitnesses. However, some of the strongest claims can be considered to lie in the design qualities of the craft itself and the spread of those features to other pioneers. The ability of the Wrights to demonstrate the source of, and in many cases explain the features that they combined and developed into the first working airplane (aeroplane), along with the ability to see these same features turn up in later craft is among the most powerful evidence of what they accomplished.

Many earlier attempts featured powerful powerplants or very light powerplants. Many had wing designs of some effectiveness. Many had the ability to glide (translate forwards speed into lift) and some had control mechanisms. The Wright Brothers' patented three-axis system of control, using wing warping (later supplanted by other 3-axis control systems), an effective wing design for the craft's weight, a light enough motor with power to maintain steady flight, an effective system to turn the engine power into thrust (the propeller), and some other features allowed it to be significantly better than any previous manned flying machine. The careful balance between all these areas are seen in any craft capable of sustained flight, and they first happened in the flyer.

Still, controversy in the credit for invention of the airplane has been fuelled by the Wrights' secrecy while their patent was prepared, by the pride of nations, by the number of firsts made possible by the basic invention, and other assorted issues.

Flight issues about whether crafts have been aided by ground effect for their flights, if it has been verified that a craft rose above a height where it could take advantage of even some ground effect can be a source of debate as many counter-claims also did not fly very high.

Another source of attack is that some of the recreations of the Wright Flyer do not fly. The reasons for failures of recreations usually stem from an inability to know exactly the Wrights' design and to duplicate the conditions of the flight. Things that even the Wrights do not know about the Flyer I that enabled it to fly are lost to history, such as things like the octane of the fuels used, and the small details of aerodynamics that can have disproportionate effect on the ability of planes to fly. The Wrights' initial troubles with their own recreation, the Flyer II, makes the matter even harder. Regardless, some recreations do fly, and the Flyer II's impressive performance and flights largely vindicate the design.

After their Kitty Hawk flights, which used a rail but no mechanical assistance in windy conditions, the Wrights developed a weight-powered catapult in Ohio to aid initial acceleration. This method of launching has been the source of controversy for some attacks on the Wrights' claim. Some consider that a plane incapable of taking off using its own power could not be a true aircraft, but choosing a non-standard definition does not necessarily exclude the Wrights.

Just as many aircraft do not have enough power to take off in certain conditions, the Flyer's trouble with achieving its take off speed on land is not a real issue. The Flyer did manage to get off the ground under its own power in some instances, and its powered and controlled flights after it was aided in achieving its take-off speed by the catapult largely redeem it. Furthermore, if an aircraft does not have enough peak power to overcome the extra drag from being in contact with the ground, some other means must be found to overcome it. This is done in a number of ways. In modern aircraft a landing gear and long runways enable them to build up to take-off speed. This important advancement would have to wait till Alberto Santos-Dumont and the flight of the 14-Bis to be implemented in aircraft. This machine used the Wright's essential developments. Catapults do remain in use on aircraft carriers where planes cannot build enough speed to take off, and these still make use of landing gear.

Most counter-claims to having the 'first plane' often have some truth to them. Many heavier-than-air aircraft became airborne before the Wrights but lacked control. Endlessly more advanced machines came after. But the Wright Flyer stands out as the first practical flying machine (airplane/aeroplane) with a combination of features not used before but included in all that came later to this day (effective wings, 3-axis control, an effective system to generate power and turn into thrust, and an effective takeoff system).

The Smithsonian issue

In the early 1900s professor Samuel P. Langley was secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He had a claim to being "father of flight" as he had for many years worked on gliders and successful powered models, and his assistant C. M. Manley was actually employed by the US government to construct aircraft for military use. His full-sized planes, however, were complete failures at flight. When the Smithsonian proposed a display that would not have made this clear, Orville Wright responded by loaning the Flyer I to the London Science Museum. Orville stated it wouldn't be returned until he and his brother were acknowledged as the "Fathers of Powered Flight". The Smithsonian eventually agreed, but the Flyer remained at Kensington in London until 1948. On November 23, 1948 the executors of the estate of Orville Wright wrote a contract with the Smithsonian Institute regarding the display of the aircraft, stating that "Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight." If this wasn't fulfilled the Flyer would be returned to the heir of the Wright brothers.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

See Paul Laurence Dunbar for the Wrights' contributions to the career of the distinguished African American poet.

Effect on Dayton

See Dayton for city history. The Wrights contributions to the city of Dayton were and remain immeasurable. From their use of local materials, when Requarth Lumber Company wood was used to construct the Flyer I and other airplanes, to the encouragement of local arts and sciences, as with Dunbar, to their financial and political contribution as with the massive Air Force base and museum, the Wright Brothers changed the city's history.

Ohio/North Carolina Dispute

The states of Ohio and North Carolina both take credit for the Wright Brothers and their world-changing invention - Ohio because the brothers developed and built their design in Dayton, and North Carolina because Kitty Hawk was the site of the first flight. With a spirit of friendly rivalry, Ohio has adopted the informal slogan "Birthplace of Aviation" (later "Birthplace of Aviation Pioneers", with a tip of the hat to not only the Wrights, but also John Glenn and Neil Armstrong, both Ohio natives.) North Carolina has also adopted the slogan "First In Flight" and includes the theme on state license plates.

As the positions of both states can be factually defended, and neither state plays an insignificant role in the history of flight, neither state truly has a complete claim to the Wrights' accomplishment. It was in Ohio, however, where the Wright Brothers' many inventions were made and where the 1903 Wright Flyer was manufactured prior to its partial disassembly and shipment to North Carolina.

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end