Optical isomerism

|

|

Optical isomerism is a form of isomerism (specifically stereoisomerism) whereby the different 2 isomers are the same in every way except being non-superposable mirror images1 of each other. Optical isomers are known as chiral molecules (prounounced ki-rall) .

The l-form of an optical isomer rotates the plane of polarization of a beam of polarized light that passes through a quantity of the material in solution counterclockwise , the d-form clockwise. It is due to this property that it was discovered and from which it derives the name optical. The property was first observed by Louis Pasteur in 1848 in racemic acid.

The study of optical isomerism is now called stereochemistry. Optical isomers are often called stereoisomers (in fact, stereoisomers constitute a more general group, since stereoisomerism needn't necessarily imply optical activity).

Two types of molecules which differ only in their relative stereochemistry are said to be enantiomers of each other. A mixture of equal amounts of both enantiomers is said to be a racemic mixture.

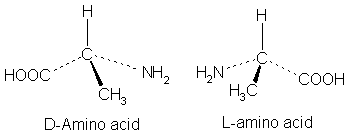

This form of isomerism can arise when an atom (usually carbon) is surrounded by four different functional groups. Swapping two of the groups can arise in two different molecules - mirror images of each other.

A rule of thumb for determining the isomeric form (usually called D- and L-)2 of an amino acid, is the "CORN" rule. The groups:

COOH, R, NH2 and H (where R is an unnamed carbon chain) -- - -

are arranged around the chiral center carbon atom. If these groups are arranged clockwise around the carbon atom, then it is the D-form. If anti-clockwise, it is the L-form.

| Contents |

Properties of optical isomers

They are identical with respect to ordinary chemical reactions, but differences arise when they are in the presence of other chiral molecules. For example Spearmint chewing gum and Caraway seeds respectively contain L-carvone and D-carvone - enantiomers of carvone. These smell different to most people because our taste receptors also contain chiral molecules which behave differently in the presence of different enantiomers.

D-form Amino acids tend to taste sweet, whereas L-forms are usually tasteless. This is again due to our chiral taste molecules. The smells of oranges and lemons are examples of the D and L enantiomers.

Penicillin works by stereoisomeric means. The antibiotic only works on peptide links of D-alanine which occur in the cell walls of bacteria - but not in humans. The antibiotic can only kill the bacteria, and not us, because we don't have these D-amino acids.

The anti-nausea drug Thalidomide was widely prescribed to pregnant women until it was linked to birth defects. It was later discovered that one enantiomer was responsible for the teratogenic effects.

A new approach, the Cahn Ingold Prelog priority rules, uses the R-... or S-... to name the chiral molecules based on the atomic numbers of the atoms or groups of atoms, the ligands, that are attached to the chiral center. The ligands are given a priority (the higher the atomic number the higher the priority) and if the priorities increase in a clockwise direction, they are said to be R-. Otherwise, if they are prioritized in a counterclockwise direction they are said to be S-. The R/S scheme is not mappable to any of the previously mentioned notations; they are based on the direction of rotation of polarized light and the R/S scheme is based on atomic number. One cannot predict the other.

Photons in polarized light all oscillate in a geometric plane as opposed to the random oscillations they present normally. That plane is bisected by an axis determined by the photon's direction of travel. In other words: optically active isomers rotate the plane that the photons oscillate in. The polarized light is actually rotated in a racemic mixture as well, but it is rotated to the left or right each time it passes through the one of the two optically active isomers, that are actually enantiomers of each other, and yielding a net rotation of zero degrees. Since it is rotated a small amount each time it interacts with or passes through the atoms and particles that make up an optically active molecule. This assumes that it will pass through an equal number of dextro and levo molecules. The rules of entropy should assure such a system, and give us equations to calculate the rotation of the polarized light based upon the concentrations of all of the optically active isomers in the solution, and the amount of solution that the polarized light passes through.

See also

Notes

Note 1: The term non-superposable distinguishes mirror images which are superposable, such as the mirror image of the letter "A", on the original, from those that aren't. The classic example of this are human hands. The left hand is a non-superposable mirror image of the right hand: No matter how the two hands are oriented relative to one another, one cannot line up all the major features of one hand with the other, whereas such an operation is trivial for a non-chiral mirror image (e.g., the letter "A").

Note 2: The convention of designating one enantiomer of some compounds as D-, and the other as L-, leads to considerable confusion. This designation does not indicate which enantiomer is dextrorotatory and which is levorotatory. Rather, it says that the compound's stereochemistry is related to that of the dextrorotatory or levorotatory enantiomer of glyceraldehyde. Nine of the nineteen L-amino acids commonly found in proteins are dextrorotatory (at a wavelength of 589 nm), and D-fructose is also referred to as levulose because it is levorotatory. The designations (+) and (-), however, indicate optical isomers that rotate plane polarized light to the right and left, repectively.

External links

- http://www.chemistry.mcmaster.ca/berti/3f03/special_stereochemistry.pdf

- http://www.chem.umd.edu/courses/chem233mazz/chapternotes/chapter9notes.pdffr:Énantiomère

nl:Optische isomerie fi:Optinen isomeria pl:Izomeria optyczna