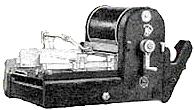

Mimeograph machine

|

|

The Mimeograph machine (commonly abbreviated to "Mimeo"), or stencil duplicator was a printing machine that was far cheaper per copy than any other process in runs of several hundred to several thousand copies. It was not capable of photocopying a document, as a special stencil had to be prepared by hand. It has been largely supplanted by photocopying and offset printing.

It used waxed tissue paper "stencils". These were placed in a typewriter to create the original; the impact of the typewriter key displaced the wax, making the tissue paper permeable to the oil-based ink. The stencil was wrapped around the drum of the (manual or electrical) machine which was filled with ink. When a blank sheet of paper was drawn between the rotating drum and a pressure roller, ink was forced out through the marks on the stencil. The paper had a surface texture like bond paper, and the ink was usually black, although green and red inks were available. A special ball-tipped stylus could be used to cut stencils by hand against a patterned plastic card, but one had to write carefully or else a loop would likely tear a hole in the tissue paper, resulting in a black blob being printed. Mistakes could be corrected by applying "correction fluid" (wax dissolved in a solvent; known as "corflu" and "obliterine", the latter being a former Australian trademark) with a small brush, then re-typing over it. If one put the stencil on the drum wrong-side-out, one's copies came out mirror-imaged. The process was messy, and ink would often get on one's hands and the pressure roller. In addition the striking surface of the letters on the typewriter would quickly become clogged with wax; the closed letter forms, such as "o" or "b" making a stencil cut that resulted in black blobs instead of white space in the center.

Another device called an electrostencil machine could make mimeo stencils from an already-printed original. It worked by scanning the original on a rotating drum with a moving optical head, and burning through the blank stencil with an electric spark in the places where the optical head detected ink. It was slow and filled the air with ozone and other pollutants, and copies produced from electrostencils had worse quality (less sharpness to the letters) than copies made from typed stencils. A skilled mimeo operator using an electrostencil and a very coarse half-tone screen could make acceptable printed copies of a photograph. This took considerable care both in preparing the stencil and in maintaining evenness of the ink flow during printing. During the declining years of the mimeograph, some people made stencils with computers and dot-matrix impact printers.

Gestetner, Risograph, and other companies still make and sell highly automated mimeograph-like machines externally similar to photocopiers, as the mimeo process is faster and less expensive than xerography for moderate to large print runs, although the image quality is inferior. The modern version of a mimeograph is called a digital duplicator and contains a scanner, a thermal head for stencil cutting, and a large roll of stencil material entirely inside the unit, making the stencils and mounting and unmounting them from the print drum automatically, making it almost as easy to operate as a photocopier. Risographs are the best known of these machines.

Origins of the Mimeograph: Thomas Edison received US patent 180,857 (http://edison.rutgers.edu/patents/00180857.PDF)) for "Autographic Printing" on August 8, 1876. The patent covered the electric pen, used for making the stencil, and the flatbed duplicating press. In 1880 Edison obtained a further patent, US 224,665 (http://edison.rutgers.edu/patents/00224665.PDF): "Method of Preparing Autographic Stencils for Printing", which covered the making of stencils using a file plate, a grooved metal plate on which the stencil was placed which perforated the stencil when written on with a blunt metal stylus. Edison did not coin the word "mimeograph", which was first used (http://edison.rutgers.edu/NamesSearch/SingleDoc.php3?DocId=CA035A) by Albert Blake Dick when he licensed Edison's patents (http://edison.rutgers.edu/NamesSearch/SingleDoc.php3?DocId=LB024149) in 1887. Others who worked concurrently on the development of stencil duplicating were Eugenio de Zaccato and David Gestetner, both in Britain.

The term "Mimeograph" was originally protected as a trademark, however over time the term became generic and is now an example of a genericized trademark [1] (http://www.bartleby.com/61/68/M0306800.html). "Roneograph" (also "Roneo machine") was another trademark used for mimeograph machines.

Mimeographs were used extensively in the production of fanzines in the middle 20th century, before photocopiers became widespread. In sufficient quantities, however, they are still more economical.

Certain typographical practices were peculiar to mimeographical publication, due to the tendency of the stencil to tear, thus becoming useless. Underlining was neither used in spaces nor on the letters with descenders. The expression of irony by crossing out letters was done with a forward slash, not a hyphen. This differs from the method in hypertext.

Penelope Rosemont pioneered a surrealist technique of peeling the backing away from the stencil to create a "mimeogram".

See also: duplicating machines, List of duplicating processes