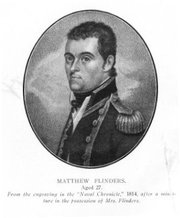

Matthew Flinders

|

|

Matthew Flinders (16 March 1774 - 19 July 1814) was one of the most accomplished navigators and chartmakers of his age. In a career that spanned just over twenty years, he sailed with Captain William Bligh, circumnavigated and named Australia, survived shipwreck and disaster only to be imprisoned as a spy, identified and corrected the effect of iron ships upon compass readings, and wrote the seminal work on Australian exploration A Voyage To Terra Australis.

| Contents |

Biographical information

Born in Donington, Lincolnshire, England, the young Matthew Flinders had his hunger for exploration and knowledge whetted by the tale of Robinson Crusoe, and at the age of fifteen he joined the navy. Later, he sailed with Captain Bligh on The Providence, transporting breadfruit from Tahiti to Jamaica.

Later, Flinders sailed to Australia on The Reliance, establishing himself as a fine navigator and cartographer, and in 1796 explored the coastline around Sydney in a tiny open boat called Tom Thumb. In 1798 he circumnavigated Van Diemen's Land (later renamed Tasmania) aboard the sloop Norfolk, therefore proving it to be an island. The passage between the Australian mainland and Tasmania became known as Bass Strait after the ships' doctor, George Bass, and a large island was named Flinders Island.

On 17 April 1801 Flinders married Ann Chappell, but was soon forced to leave his new wife when the British Government sent him back to Australia. He set out that July, in command of The Investigator, to produce a detailed survey of the coastline of Australia, the southern coast of which was still unknown.

Between December 1801 and June 1803, Flinders charted the entire coastline of Australia. He sighted Cape Leeuwin on 6 December and worked his way eastwards until he reached Fowlers Bay on the 28 January. From that point on, the coastline was uncharted.

Nicolas Baudin and the Meeting at Encounter Bay

On 8 April, Flinders, while sailing east, met up with the French explorer Nicolas Baudin, who was sailing west aboard Le Gιographe. Both men had been sent by their respective governments on separate expeditions to map the unknown southern coastline of Australia. Both men of science, Flinders and Baudin met and exchanged details of their discoveries, and sailed together to Sydney to resupply. Flinders would later name the site of their meeting Encounter Bay.

The meeting at Encounter Bay by the two expeditions marked the point at which the entire coastline of continental Australia became mapped.

By June 1803, the hull of Investigator had deteriorated to such a degree that Flinders was forced to abandon his survey of the northern coastline of Australia. He returned to Sydney by the west coast, thus completing his circumnavigation of Australia.

Flinders set sail for England aboard The Porpoise to secure another vessel from the British Government with which to complete his survey, but was shipwrecked on the Great Barrier Reef. Remarkably, Flinders navigated the ship's cutter across open sea back to Sydney, a distance of some 700 miles, and arranged for the rescue of the marooned crew on Wreck Reef.

Flinders next attempted to return to England aboard The Cumberland, but the poor condition of the schooner forced it to put in at Mauritius for repairs on 17 December. Unbeknownst to Flinders, England was now at war with France again, and the French governor, General De Caen, had Flinders detained as a prisoner of war. His imprisonment was, in reality, due to misunderstandings and indignancies by both parties and lasted for almost seven years.

Flinders finally returned to England in October 1810, where he immediately began work on preparing A Voyage to Terra Australis for publication. On 18 July 1814, the book was published. The next day, Matthew Flinders died, aged only 40.

Naming Australia

Flinders_View_of_Port_Jackson_taken_from_South_Head.jpg

The first writer in English to use the word "Australia" was Alexander Dalrymple in his An Historical Collection of Voyages and Discoveries in the South Pacific Ocean, published in 1771, but he used it to refer to the whole South Pacific region, not specifically to the Australian continent. In 1793 George Shaw and Sir James Smith published Zoology and Botany of New Holland, in which they wrote of "the vast island, or rather continent, of Australia, Australasia or New Holland."

Matthew Flinders, who proved that New Holland and New South Wales were part of the same land mass, possessed a copy of Dalrymple's book, and it seems likely he borrowed the word from this source and applied it to the Australian continent. In 1804 he wrote to his brother: "I call the whole island Australia, or Terra Australis." Later that year he wrote to Sir Joseph Banks and mentioned "my general chart of Australia." He continued to promote the use of the word until his arrival in London in 1810. Here he found that Banks did not approve of the name, and that "New Holland" and "Terra Australis" were still in general use. As a result, Flinders's 1814 book was published under the title A Voyage to Terra Australis despite his objections.

In this book, however, Flinders wrote: "The name Terra Australis will remain descriptive of the geographical importance of this country... [but] had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term, it would have been to convert it into Australia; as being more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth."

Flinders's book was widely read and gave the term "Australia" general currency. Governor Lachlan Macquarie of New South Wales became aware of Flinders' preference for the name Australia and used it in his dispatches to England. In 1817 he recommended that it be officially adopted. In 1824 the British Admiralty finally accepted that the continent should be known officially as Australia.

Legacy

Flinders name is now associated with many geographical features and places in Australia in addition to Flinders Island, in Bass Strait. These include the Flinders mountain range and Flinders Ranges National Park, Flinders University in Adelaide, Flinders Street in Melbourne and the suburb of Flinders, also in Melbourne.

The noted archaelogist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie was his grandson.

Bryce Courtenay's novel Matthew Flinders' Cat also features Flinders. Flinders' cat Trim is famous for accompanying him on his voyages.

Works

- A Voyage to Terra Australis, with an accompanying Atlas. 2 vol. London : G & W Nicol, 18. Juli 1814 (the day before Flinders' death)

References

- Ernest Scott: The Life of Captain Matthew Flinders, RN. Sydney : Angus & Robertson, 1914

- Geoffrey Rawson: Matthew Flinders' Narrative of his Voyage in the Schooner Francis 1798, preceded and followed by notes on Flinders, Bass, the wreck of the Sidney Cove, &c. London : Golden Cockerel Press, 1946

- Sidney J. Baker: My Own Destroyer : a biography of Matthew Flinders, explorer and navigator. Sydney : Currawong Publishing Company, 1962

- K. A. Austin: The Voyage of the Investigator, 1801-1803, Commander Matthew Flinders, R.N. Adelaide : Rigby Limited, 1964

- James D. Mack: Matthew Flinders 17741814. Melbourne : Nelson, 1966

- Geoffrey C. Ingleton: Matthew Flinders : navigator and chartmaker. Guilford, Surrey : Genesis Publications in association with Hedley Australia, 1986

- Tim Flannery: Matthew Flinders' Great Adventures in the Circumnavigation of Australia Terra Australis. Melbourne : Text Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 1876485922

- Miriam Estensen: Matthew Flinders : The Life of Matthew Flinders. Crows Nest, NSW : Allen & Unwin, 2002. ISBN 1865085154

External Links

- The Matthew Flinders Electronic Archive (http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/flinders/archive.html).

- Related literature (http://gutenberg.net.au/pages/flinders.html) (Project Gutenberg Australia).

- See also: List of explorersde:Matthew Flinders