Magna Carta

|

|

Note: As there is no definite article in Latin, the document is properly referred to as simply "Magna Carta" rather than "the Magna Carta."

Magna Carta (Latin for "Great Charter", literally "Great Paper") is an English 1215 charter which limited the power of English Monarchs, specifically King John, from absolute rule. Magna Carta was the result of disagreements between the Pope and King John and his barons over the rights of the king: Magna Carta required the king to renounce certain rights and respect certain legal procedures, and to accept that the will of the king could be bound by law. Magna Carta is widely considered to be the first step in a long historical process leading to the rule of constitutional law.

| Contents |

History of Magna Carta

After the Norman Conquest in 1066 and advances in the 12th century, the English king had by 1199 become the most powerful monarch Europe had ever seen. This was due to a number of factors including the sophisticated centralised government created by the procedures of the new Norman rulers combined with the native Anglo-Saxon systems of governance, as well as extensive Anglo-Norman land holdings in Normandy. However, after King John took power in the early 13th century, a series of stunning failures on his part led the barons of England to revolt and place checks on the king's unlimited power.

The failures of King John were threefold. First, there was a general lack of respect for King John because of the way he took power. There were two candidates to take the place of the previous king, Richard the Lionheart, when he died in 1199: John, and his nephew Arthur of Brittany in Normandy. John captured Arthur and imprisoned him and he was never heard from again. Although Arthur's murder was never proven, it was assumed and many saw it as a black mark against John that he would murder his own family to be king.

Secondly, after Philip Augustus, the King of France, seized most of the English holdings in France, the English barons demanded of their king that he retake the land, and while he attempted to do so 8 years later, the effort came to failure at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. John was given the nickname of "Lackland" not because of this loss, but because he had received no land rights in the continental provinces, unlike his elder brothers.

The third failure of John was when he became embroiled in a dispute with the Church over the appointment of the office of Archbishop of Canterbury. John wanted to appoint his own Archbishop and the Church wanted to appoint Stephen Langton. This struggle went on for several years during which England was placed under a sentence of interdict and finally John was forced to submit to the will of the Church in 1213.

Runnymede and afterwards

By 1215, the barons of England had had enough: they banded together and took London by force on June 10, 1215. They forced King John to agree to a document known as the 'Articles of the Barons', to which his Great Seal was attached in the meadow at Runnymede on June 15, 1215. In return, the barons renewed their oaths of fealty to King John on June 19, 1215. A formal document to record the agreement between King John and the barons was created by the royal chancery on July 15: this was the original Magna Carta. An unknown number of copies of this document were sent out to officials, such as royal sheriffs and bishops.

The most significant clause for King John at the time was clause 61, known as the "security clause", the longest portion of the entire document. This established a committee of 25 Barons who could at any time meet and over-rule the will of the King, through force by seizing his castles and possessions if needed. This was based on a mediæval legal practice known as distraint, which was commonly done, but it was the first time it had been applied to a monarch. In addition, the King was to take an oath of loyalty to the committee.

King John had no intention of honouring Magna Carta, as it was sealed under extortion by force, and clause 61 essentially neutered his powers as a monarch, making him King in name only. He renounced it as soon as the barons left London, plunging England into a civil war, known as the First Barons' War. Pope Innocent III also immediately annulled the "shameful and demeaning agreement, forced upon the king by violence and fear." The Pope rejected any call for rights, saying it impaired King John's dignity.

John died in the middle of the civil war, of dysentery, on October 18, 1216, and it quickly changed the nature of the war. His nine year old son, King Henry III, was next in line for the throne. The royalists believed the rebel barons would find the idea of loyalty to the child Henry more palatable, and so the child was swiftly crowned in late October 1216 and the war ended. On November 12, 1216, Magna Carta was reissued in Henry's name by his regents with some of the clauses, including the contentious clause 61, omitted; Magna Carta was again reissued by Henry's regents in 1217. When he turned eighteen in 1225, Henry III himself reissued Magna Carta a third time, this time in a shorter version with only 37 articles.

Henry III ruled for 56 years (the longest reign of an English Monarch in the Mediæval period) so that by the time of Henry's death in 1272, Magna Carta had become a settled part of English legal precedent, and more difficult for a future monarch to annul as King John had attempted nearly three generations earlier. Henry III's son and heir Edward I's Parliament reissued Magna Carta for the final time on 12 October, 1297 as part of a statute known as Confirmatio cartarum (25 Edw. I), reconfirming Henry III's shorter version of Magna Carta from 1225.

Magna Carta of 1215

Magna Carta guaranteed certain English political liberties and contained clauses providing for a church free from domination by the monarchy, reforming law and justice, and controlling the behaviour of royal officials.

A large part of Magna Carta was copied, nearly word for word, from the Charter of Liberties of Henry I, issued when Henry I ascended to the throne in 1100, which bound the king to certain laws regarding the treatment of church officials and nobles, effectively granting certain civil liberties to the church and the English nobility.

Magna Carta is composed of 63 different clauses or articles, the majority of which are very specific to the 13th century and of temporary importance. For example, it repealed certain royal taxes that were unpopular and reduced the amount of hunting land that was royal and thus off-limits to most people. The text displays its origin as a product of negotiation, haste and many hands.

One of the most important clauses that would have the longest lasting effect was Article 39 according to which

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

This meant the King must judge individuals according to the law, and not according to his own will. This was a check on the power of the king and the first step in the long road to a constitutional monarchy.

Significance

Although the first version of Magna Carta remained in effect only a few weeks, its reissue following John's death in autumn 1216 and the definite reissue of 1225 made it perpetual, the first of England's statutes and a cornerstone of the British constitution. Henry III and his successors evaded and broke provisions in the charters; indeed, the absolute power of the English Monarchy, despite Magna Carta, actually grew during the Medieval period. For example, in his historical play King John, William Shakespeare did not mention Magna Carta. However, a fundamental principle had been asserted and accepted by the King: monarchy was subject to the law, and the thirty reissues of Magna Carta during the mediæval era reminded him of this fact, even if he didn't always abide by it. Magna Carta was not considered a particularly important document during the medieval period, during which the power of the English crown grew.

The charter became increasingly important in the 17th century as the conflict between the Crown and Parliament grew. Magna Carta was repeatedly revised and other documents created such as the Provisions of Oxford, guaranteeing greater rights to greater numbers of people, thus setting the stage for the British Constitutional monarchy.

Many later attempts to draft constitutional forms of government, including the United States Constitution, trace their lineage back to this source document. Numerous copies were made each time it was issued, so all of the participants would each have one. Several of those still exist and some are on permanent display.

The version of Magna Carta from 1297 is still part of English law, although only part of the introductory sentences, three articles, and the ending remain in force: the remaining 34 articles have been repealed or superseded. Today, Magna Carta has little practical legal use. Despite this, it is still used in arguments about reform of the jury system.

The articles currently in force are articles one, nine and twenty-nine of the 1297 version, which are broadly similar to articles one, thirteen, thirty-nine and forty of the 1215 version.

Magna Carta and the Jews in England

Magna Carta contained two articles related to money lending and Jews in England. Jewish involvement with money lending caused Christian resentment, because the Church forbade the lending of money at interest (known at the time as usury); it was seen as vice (such as gambling, an un-Christian way to profit at others' expense) and was punishable by excommunication, although Jews, as non-Christians, could not be excommunicated and were thus in a legal grey area. Secular leaders, unlike the Church, tolerated the practice of Jewish usury because it gave the leaders opportunity for personal enrichment. This resulted in a complicated legal situation: debtors were frequently trying to bring their Jewish creditors before Church courts, where debts would be absolved as illegal, while the Jews were trying to get their debtors tried in secular courts, where they would be able to collect plus interest. The relations between the debtors and creditors would often become very nasty. There were many attempts over centuries to resolve this problem, and Magna Carta contains one example of the legal code of the time on this issue:

- If one who has borrowed from the Jews any sum, great or small, die before that loan be repaid, the debt shall not bear interest while the heir is under age, of whomsoever he may hold; and if the debt fall into our hands, we will not take anything except the principal sum contained in the bond. And if anyone die indebted to the Jews, his wife shall have her dower and pay nothing of that debt; and if any children of the deceased are left under age, necessaries shall be provided for them in keeping with the holding of the deceased; and out of the residue the debt shall be paid, reserving, however, service due to feudal lords; in like manner let it be done touching debts due to others than Jews.

After the Pope annulled Magna Carta, future versions contained no mention of Jews. Jews were seen by the Church as a threat to their authority, and the welfare of Christians, because of their special relationship to Kings as moneylenders. "Jews are the sponges of kings," wrote the theologian William de Montibus, "they are bloodsuckers of Christian purses, by whose robbery kings dispoil and deprive poor men of their goods." The anti-semitic attitudes came about in part because of Christian nobles who permitted the otherwise illegal activity to occur, a symptom of the ongoing power struggle between Church and State.

Copies

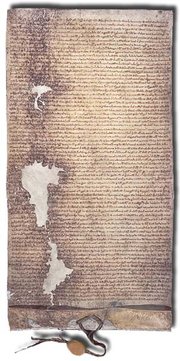

The original version of Magna Carta sealed by King John in 1215 has not survived. Four contemporaneous copies (known as "exemplifications") remain, all of which are located in the UK: two held by the British Library, one at Lincoln Cathedral, and one at Salisbury Cathedral. Thirteen other versions of Magna Carta dating to 1297 or earlier survive, including four from 1297.

In 1952 the Australian Government purchased a 1297 copy of Magna Carta for £12,500. This copy is now on display in the Members' Hall of Parliament House, Canberra. In September 1984, Ross Perot purchased another copy of the 1297 issue of Magna Carta. Perot's copy is on display at his international company, Perot Systems.

See also

- Fundamental Laws of England

- History of democracy

- Image:Magcarta.JPG (certified copy)

References

- Article from Australia's Parliament House about the relevance of Magna Carta (http://www.aph.gov.au/Senate/pubs/occa_lect/flyers/171097.htm)

External links

- The British Library (http://www.bl.uk/collections/treasures/magna.html)

- magnacharta.com (http://www.magnacharta.com/articles/magna.htm)

- The influence of Magna Carta (http://www.archives.gov/exhibit_hall/featured_documents/magna_carta/legacy.html) on the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights

- historicaldocuments.com (http://www.historicaldocuments.com/MagnaCarta.htm)

- Parliament House, Canberra, Australia (http://www.aph.gov.au/jhd/visiting/architect/build.htm)

- Text of Magna Carta (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/magnacarta.html) with introductory historical note. From the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- Notes prepared by Nancy Troutman (http://www.constitution.org/eng/magnacar.htm)af:Magna Carta

ast:Carta Magna bg:Велика харта на свободите da:Magna Carta de:Magna Carta fr:Magna Carta id:Magna Carta it:Magna Carta he:מגנה כרטה nl:Magna Charta ja:マグナ・カルタ pl:Magna Charta Libertatum pt:Magna Carta ru:Великая хартия вольностей sk:Magna charta libertatum sl:Magna Carta fi:Magna Carta zh:大憲章