MAD Magazine

|

|

MAD is an American humor magazine founded by publisher William Gaines and editor Harvey Kurtzman in 1952. Ostensibly aimed at young readers, it satirizes American pop culture, deflates stuffed shirts and pokes fun at common foibles. It is the last surviving title from the notorious and critically-acclaimed EC Comics line. Publisher Gaines had suffered greatly from censorship, which had literally driven his prior line of EC horror comics from the stands.

| Contents |

History

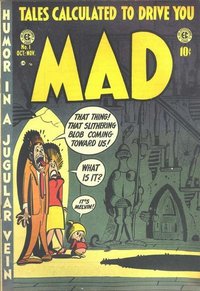

MAD was first published as a comic book entitled Tales Calculated To Drive You Mad (Oct.–Nov. 1952). Written almost entirely by Harvey Kurtzman, it largely concentrated on satirizing popular newspaper comics and comic books, and the popular movies of the day. The popular myth is that it was converted into a magazine to escape the strictures of the Comics Code Authority, which was imposed in 1955 following Senate hearings on juvenile delinquency. Actually, Kurtzman received a lucrative offer from another publisher, only staying when Gaines agreed to convert "MAD" to a "slick" magazine. The immediate practical result was that MAD acquired a broader range in both subject matter and presentation. Magazines also had wider distribution than comic books, and a more adult readership.

Though there are antecedents to "MAD"s style of humor in print, radio, and film, the overall package was a unique one that stood out in a staid era. Throughout the 1950s MAD featured brilliant parodies of American popular culture illustrated by such luminaries as Jack Davis, Bill Elder, and Wally Wood, each with his own style. They combined a sentimental fondness for the familiar staples of American culture—such as Archie and Superman—with a keen joy in exposing the fakery behind the image—see their pieces entitled "Starchie" and "Superduperman."

Original editor Kurtzman left in 1956 following a business dispute with Gaines, and was replaced by Al Feldstein, who oversaw the magazine during its greatest heights of circulation. Feldstein retired in 1984, and was replaced by the team of Nick Meglin and John Ficarra, who co-edited "MAD" for the next two decades. Meglin retired in 2004; Ficarra continues to edit the magazine today.

MAD is often credited by social theorists with filling a vital gap in political satire in the 1950s to 1970s, when Cold War paranoia and a general culture of censorship prevailed in the United States, especially in literature for teens. The rise of such factors as cable television and the Internet seems to have diminished such influence of MAD somewhat, although it remains a widely distributed magazine. In a way, MAD's power has been undone by its own success; what was subversive in the 1950s and 1960s is now commonplace. However, its impact on three generations of humorists is incalculable, as can be seen in the frequent references to MAD Magazine on the animated series The Simpsons.

MAD was noted for its absence of advertising, enabling it to skewer the excesses of a materialist culture without fear of advertiser reprisal. The magazine often featured numerous parodies of ongoing American advertising campaigns. During the 1960s, it satirized such topics as hippies, the Vietnam War, and drug abuse. The magazine gave equal time to counterculture drugs such as cannabis as well as to mainstream drugs such as tobacco and alcohol. Although one can detect a generally liberal tone, the magazine always slammed Democrats as mercilessly as Republicans.

For tax reasons, Gaines had sold his company in the early 1960s to the Kinney Corporation, which also acquired Warner Bros by the end of that decade. Though technically an employee for 30 years, the fiercely independent Gaines was largely permitted to run MAD without corporate interference. Following Gaines' death in 1992, though, MAD became more ingrained within the AOL Time Warner conglomerate.

In 2001, the magazine broke its long-standing taboo and began running advertising. Today, the magazine is published by a branch of DC Comics and in recent years has used its advertising revenue to increase the use of color. The MAD logo has remained virtually unchanged since the late 1950s, save for the decision to italicize the lettering beginning in the late 1990s.

Recurring Features

In a parody of Playboy's "foldout" cheesecake pictures, each issue of MAD from 1964 on featured a "fold-in" on its inside back cover, designed by artist Al Jaffee. A question would be asked, which apparently was illustrated by a picture taking up the bulk of the page. When the page was folded inwards, the inner and outer fourths of the picture combined to give a surprising answer in both picture and words.

Dave Berg produced "The Lighter Side of..." which often satirized the suburban lifestyle, capitalism and the generation gap. The feature eventually became notorious for its corny gags and garishly outdated fashion choices, but was quite sharp in its first decade, providing the sort of Americana-based humor that standups like Shelley Berman and Alan King performed successfully onstage. "The Lighter Side" feature was retired with Berg's death.

Antonio Prohias' wordless "Spy vs. Spy," the never-ending battle between the iconic Black Spy and White Spy, has lasted longer than the Cold War which inspired it. The strip was a silent parable about the futility of mutually-assured destruction, with various elaborate deathtraps designed in Prohias' thick line. Almost always, these traps would boomerang back on whichever Spy had originally concocted it; there was no pattern or order to which spy would be killed in which episode. A female "Gray Spy" occasionally appeared, the difference being that she never lost. Prohias eventually retired from doing the strip; "Spy vs. Spy" continues in newer hands.

Don Martin, who would become billed as "MAD's Maddest Artist," drew regular one-page cartoons featuring lumpen characters with apparently hinged feet. The grotesque sight gags were frequently punctuated by an array of bizarre sound effects such as GLORK, PATWANG-FWEEE, or GAZOWNT-GAZIKKA. When Martin first joined MAD, he employed a scratchy style, but this developed into a rounder, more cartoony look. Martin's wild physical comedy would eventually make him the signature artist of the magazine, but his long association with MAD ended in some rancor.

Sergio Aragones, whose work is almost uniformly silent, has written and drawn his "Looks At..." feature for over 40 years. He is known for his remarkable speed and cartooning facility. Aragones also provides the "MAD Marginals": tiny gag images that appear throughout the magazine in the corners, margins, or spaces between panels.

"Monroe" is an ongoing storyline about a prototypical teenaged loser. It depicts his travails in school, his dysfunctional home, and his unending troubles elsewhere. It is written by Anthony Barbieri and illustrated by Bill Wray.

Http://galleries.mugglenet.com/misc/spoofs/madmagazine/mad2comic3.jpg

A typical issue will include at least one full parody of a popular movie or television show. The titles are changed to create a play on words; for instance, "The Addams Family" became "The Adnauseum Family." The character names are generally switched in the same fashion. These articles typically run 5 pages or more, and are presented as a sequential storyline with caricatures and word balloons. The opening page or 2-page splash usually consists of the cast of the show introducing themselves directly to the reader; in some parodies, the writers sometimes attempt to circumvent this convention by presenting the characters without such direct exposition. Many parodies end with the abrupt deus ex machina appearance of outside characters or pop culture figures who are similar in nature to the movie or TV series being parodied, or who comment satirically on the theme. For example, Dr. Phil arrives to counsel the "Desperate Housewives," or the cast of "Sex and the City" show up as the new hookers on "Deadwood." Several show business stars have been quoted to the effect that the moment when they knew they'd finally "made it" was when they saw themselves thus depicted in the pages of MAD.

Several MAD premises have been successful enough to warrant additional installments, though not with the regularity of the above. Other recurring features which have appeared in MAD include:

- Advertising parodies-- too numerous to mention, though many have been written by Dick DeBartolo; these have ranged from TV ad spoofs to national campaigns to home marketing and have long provided one of the most durable sources of MAD's humor;

- Alfred's Poor Almanac-- this text-heavy page featured quick text gags, faux anniversaries, and other arcana, supposedly matched to each day of that month;

- Badly-Needed Warning Labels for Rock Albums-- written by Desmond Devlin, this series of articles mocks both the ongoing Parental Advisory labelling controversy and the musicians involved with specifically-written warning labels for particular recordings;

- Behind the Scenes at ____-- written and illustrated by various, these frequently take an "eye in the sky" approach as various vignettes and conversations are played out simultaneously, showing the reader how the participants "really" think and behave;

- Believe It Or Nuts!-- written and illustrated by various (though most often drawn by Wally Wood or Bob Clarke), this parody of the print version of Ripley's Believe It Or Not would depict alleged marvels and mundanities of the world;

- Celebrity Cause-of-Death Betting Odds-- written by Mike Snider, this long-running feature lists and "ranks" possible methods of future death for one well-known person at a time;

- Celebrity Wallets-- written by Arnie Kogen, this was a series of peeks at the notes, photographs and other memorabilia being carried around in the pockets of the famous;

- Cents-less Coupons-- written by Scott Maiko, these imitate the giveaway coupon packets found in Sunday newspapers but promote ludicrous products such as "Inbred Valley Imitation Squirrel Meat";

- Chilling Thoughts-- written by Desmond Devlin and illustrated by Rick Tulka, these featured observations or predictions about both the culture and everyday life that had supposedly dire implications;

- MAD Deconstructs Talk Shows-- written by Desmond Devlin, these take on one show at a time and purport to reveal the minute-by-minute format breakdown of America's not too spontaneous chat programs;

- Disposable Camera Photos That Didn't Make the Album-- written by Butch D'Ambrosio and illustrated by Drew Friedman, these show "candid" photographs from events like proms, bar mitzvahs or weddings, with descriptive commentary;

- Do-It-Yourself Newspaper Story-- written by Frank Jacobs, these are short text news items containing a number of blank spaces. Each space has a corresponding list of numbered fill-in-the-blank options, which grow increasingly absurd. The premise is that with appropriate mixing and matching, the article can be read in a gigantic number of permutations;

- Duke Bissell's Tales of Undisputed Interest-- written and illustrated by P.C. Vey, these absurdist one-pagers present a series of non sequiturs and bizarre references in the guise of a linear storyline;

- Ecchbay Item of the Month-- laid out to mimic a computer screen linked to eBay, these purport to sell weird and often topical collectables;

- 15 Minutes of Fame-- written by Frank Jacobs, it consists of short poems about lesser celebrities and news figures;

- The 50 Worst Things About ____-- written and illustrated by various, this is an annual article format which has thus far dealt with large catch-all topics such as "TV," "comedy," or "sports";

- The MAD Hate File-- written and illustrated by Al Jaffee, these contained a series of observational one-liners about common irritations;

- Hawks & Doves-- written and illustrated by Al Jaffee, this was a shortlived series of cartoons in which a general is exasperated by a rebellious private who keeps finding ways to create the peace symbol on his military base;

Http://www.itsgames.com/usr/ilana/mad/images/cliches/cliche18.jpg

- Horrifying Cliches-- illustrated by Paul Coker Jr. and often written by Phil Hahn, these articles visually depict florid turns of phraseology such as "tripping the light fantastic" or "racking one's thoughts"; the verbs are taken literally, and all the nouns are characterized as bizarre horned, scaled or otherwise unusual creatures; MAD also published a separate paperback of these;

- How Many Mistakes Can You Find In This Picture?-- these articles would show a widespread area such as a rock concert or a fast food outlet, and then reveal 20 visual "mistakes," which would typically be people behaving in moral or competent ways;

- MAD's ____ of the Year-- written and illustrated by various, these 4-to-6-page articles would enact an interview with a fictional representative of a particular practice or element of society (i.e. "MAD's Summer Camp Owner of the Year"; "MAD's Movie Producer of the Year");

- The MAD Nasty File-- typically written by Tom Koch and illustrated by Harry North or Gerry Gersten, this series of insult articles would caricature a variety of public figures and proceed to abuse them verbally;

- Melvin and Jenkins' Guide to _____-- written by Desmond Devlin and illustrated by Kevin Pope, these "guides" present the behavioral or attitudinal "do's and don'ts" on a variety of topics, as demonstrated by the titular pair. This is meant to be a parody of Goofus & Gallant.

- Movie Outtakes-- these are screen captures of upcoming films (generally taken from the movie trailer, given new word balloons; MAD typically times these pieces to coincide with the movie's general release, either in advance of the full parody or in lieu of it;

- Obituaries for ____ Characters-- generally written by Frank Jacobs, these alleged newspaper clippings detail the appropriate demises for fictional characters from a genre such as comic strips, advertising, or television;

- People Watcher's Guide to ____-- often written by Mike Snider and illustrated by Tom Bunk, these articles use a scenario such as "the mall" or "a cemetery" to mock specific observed behaviors;

- Pop-Off Videos-- written by Desmond Devlin and illustrated with actual music video screen captures, these one-page articles mimicked the VH1 series "Pop-Up Video," which enhanced music videos with small bits of information; MAD also published a separate standalone special issue of these;

- The MAD _____ Primer-- written and illustrated by various, MAD Primers aped the singsong writing style of Dick and Jane and dealt with a wide variety of subjects from bigotry to hockey to religion; MAD also published a "Cradle to Grave Primer" as a separate paperback, showing the complete misery-filled life of one man;

- Scenes We'd Like to See-- written and illustrated by various, these were generally one page vignettes which inverted the common conventions of moviemaking, advertising, or the culture at large, ending with a cliched character in a cliched setting, acting cowardly or saying something atypically honest;

- Six Degrees of Separation Between Anyone and Anything-- written by Mike Snider and illustrated by Rick Tulka, this feature exploits the Kevin Bacon-based game of links to humorously connect various items or people in thematic or painstakingly phrased ways rather than proximity;

- Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions-- written and illustrated by Al Jaffee, this long-running series reproduces the inane, unnecessary questions we hear every day (i.e. "Hot enough for you?" "Did that hurt?") and supplies three obnoxious responses for each; MAD has also published a separate, standalone paperback of these;

- When ____ Go Bad-- written and illustrated by John Caldwell, each article depicts the outrageous behavior allegedly found within the worst element of a certain culture or profession (i.e. "When Nuns Go Bad"; "When Clowns Go Bad"; "When Veterinarians Go Bad");

- William Shakespeare, Commentator-- written by Frank Jacobs, these articles take Shakespeare quotations out of context and apply them to such areas as movies or sports;

- The Year in Film-- written by Desmond Devlin, these ironically juxtapose movie titles of the past calendar year with news or celebrity photographs;

- You Know You're Really ___ When...-- written and illustrated by various, these would take a common condition ("You're Really Overweight When..." "You're Really a Parent When...") and present several one-liners on the theme;

Besides the above, MAD has returned to certain themes and areas again and again, such as fullblown imaginary magazines, greeting cards, nursery rhymes, Christmas carols, song parodies and other poetry (updating "Casey at the Bat" being a perennial favorite), comic strip takeoffs, and others.

Alfred E. Neuman

Http://www.leconcombre.com/alfred/img2/alfred_e_neuman_thumb.jpg

The image most closely associated with the magazine is that of Alfred E. Neuman, the curly-haired boy with a gap-toothed smile and the question "What? Me worry?" Alfred's image first appeared on the cover of the magazine within the first few years of its existence. Before that he had appeared inside a small portion of an issue. The original image of an unnamed boy with a goofy gap-toothed grin was a popular humorous graphic many years before MAD adopted it. It had been used for all manner of purposes, from U.S. political campaigns to Nazi racial propaganda to advertisements for painless dentistry. Decades ago, the magazine was sued over the copyright to the image, but prevailed by producing similar ones dating back to the late 19th century. The face is now permanently associated with MAD Magazine, and with the "What? Me worry?" motto, often appears in political cartoons as a shorthand for unquestioning stupidity. The "Alfred E. Neuman" character takes his name from Alfred Newman, a member of a well-known family of film composers, who made a series of blackout radio appearances that had amused Kurtzman years earlier. A female version of Alfred appeared for a very brief time in the late 1950s.

Recurring Images and References

Regular MAD readers have been treated to a large number of recurring in-jokes, including Neuman's catch phrase "What? Me worry?", as well as such words as potrzebie, axolotl, Cowznofski, hoo-hah, etc. In the 1950s, the magazine received a fee to promote the soft drink Moxie, and that product's logo would periodically adorn an article. Other visual elements are sheer whimsy, and frequently appear in the artwork without context or explanation. Among these are a potted plant labelled Arthur; the MAD Zeppelin (which more closely resembles an elongated hot air balloon); and an emaciated long-beaked creature who went unidentified for decades before being dubbed "Flip the Bird." The mysterious name "Max Korn" has popped up for years; reader requests to clarify the reference have been greeted with increasingly outlandish "explanations." In late 1964, MAD was tricked into purchasing the "rights" to an optical illusion in the public domain, featuring a sort of three-pronged tuning fork whose appearance defies physics. The magazine dubbed it the "MAD poiuyt" after the six rightmost letter keys on a QWERTY keyboard in reverse order, not realizing that the existing image was already known to engineers and usually called a blivet.

Contributors and Controversy

MAD also provided a showcase for some of the best satirical writers and artists of a generation. Artists such as the aforementioned Davis, Elder and Wood, as well as Mort Drucker, George Woodbridge, and Paul Coker, and writers such as Dick DeBartolo, Stan Hart, Frank Jacobs, Tom Koch, and Arnie Kogen appeared regularly in the magazine's pages.

Although "MAD" was an exclusively freelance publication, it achieved a remarkable stability, with numerous contributors remaining prominent for decades. Critics of the magazine felt that this lack of turnover eventually led to a formulaic sameness, although there is little agreement on precisely when the magazine peaked or plunged. It appears to be largely a function of when the reader first encountered "MAD"; like Saturday Night Live or The Simpsons, proclaiming the precise moment that kicked off the magazine's irreversible decline has long been sport.

MAD poked fun at this dynamic in its "Untold History of MAD Magazine," a self-reverential faux history that appeared in the 400th issue. According to the Untold History:

"The second issue of MAD goes on sale on December 9, 1952. On December 11, the first-ever letter complaining that MAD "just isn't as funny and original like it used to be" arrives."

The loudest among those who insist the magazine is no longer funny are typically supporters of Harvey Kurtzman, who had the good critical fortune to leave MAD after just 28 issues, before his own formulaic tendencies became oppressive. This also meant Kurtzman suffered the bad financial timing of departing before the magazine became a runaway success. However, just how much of that success was due to the original Kurtzman template he left for his successor, and how much can be credited to the Al Feldstein system and the depth of the post-Kurtzman talent pool, can be argued without result.

Judging from Kurtzman's final two-plus years at EC, during which MAD appeared erratically (10 issues appeared in 1954, followed by 8 issues in 1955, and 4 issues in 1956), it seems clear that he was ill-suited to the job of producing the magazine on a regular schedule. It seems equally clear that Feldstein's abilities were more workmanlike and reliable than the inimitable genius of Kurtzman. Kurtzman and Will Elder returned to MAD for a short time in the mid-1980s, as an illustrating team.

Many of the magazine's mainstays began slowing, retiring or dying in the 1980s; though the magazine was always open to new talent, the influx increased from this stage onwards. Newer contributors include Anthony Barbieri, Tom Bunk, John Caldwell, Desmond Devlin, Drew Friedman, Barry Liebmann, Hermann Mejia, Andrew J. Schwartzberg, Mike Snider, Rick Tulka, and Bill Wray.

In recent years, MAD has continued to receive complaints from fans and foes alike, sometimes over its perceived failings or because of controversial content, but generally over its decision to accept advertising. These accusers sometimes invoke the late publisher Bill Gaines, asserting that the late publisher would "turn over in his grave" if he knew of the magazine's sellout. The editors have a ready answer, pointing out that such protests are completely invalid because Gaines was cremated.

MAD Merchandising

MAD has stepped gingerly into other media. Three albums of novelty songs were released in the early 1960s. A successful off-Broadway production, "The MAD Show," was staged in 1966, featuring sketches written by MAD personnel (as well as an uncredited assist by Stephen Sondheim). An early 1970s television pilot was not picked up.

In 1980, following the success of the National Lampoon-backed Animal House, MAD lent its name to a similar risque comedy entitled Up the Academy. It was such a commercial and critical failure that MAD successfully arranged for all references to the magazine (including a cameo by Alfred E. Neuman) to be removed from future TV and video releases of the film.

A TV show was introduced in 1995 based on the magazine: MAD TV, which aired comedy segments in a fashion similar to Saturday Night Live and SCTV. However, there is no editorial connection between the sketch comedy series and the magazine. The characters from "Spy vs. Spy" have featured in animated vignettes on "MAD TV," and more recently, TV ads for Sprite soda.

While MAD frequently repackaged its material in a long series of "Super Special"-format magazines and paperbacks, MAD-related merchandise was once scarce. During the Gaines years, the publisher had an aversion to "milking" his fanbase, and expressed the fear that substandard MAD products would offend them. He was known to personally issue refunds to anyone who wrote to the magazine with a complaint. Among the few outside MAD items available in its first 40 years were cufflinks, a "straitjacket" T-shirt complete with lock, and a small ceramic Alfred E. Neuman bust. Since Gaines' death, and MAD's overt absorption into the Time Warner publishing umbrella, MAD-related merchandise has appeared regularly.

One steady form of revenue has come from foreign editions of the magazine. MAD has been published in local versions in many countries, beginning with Great Britain in 1959, and Sweden in 1960. Each new market receives access to MAD's back catalogue of articles, and is also encouraged to produce its own localized material in the MAD vein. However, the American MAD's sensibility has not always translated to other cultures, and many of the foreign editions have had short lives or interrupted publications. The Swedish, Danish, Italian, and Mexican MADs were each published on three separate occasions; Norway has had four runs cancelled. England (35 years), the Netherlands (32 years) and Brazil (31 years and counting) have produced the longest uninterrupted MAD variants.

Current foreign editions:

- Sweden, 1960-1992, 1996-2001, 2002-present;

- Germany, 1968-1993, 1998-present;

- Brazil, 1974-present;

- Finland, 1970-1971, 1981-present;

- Australia, 1980-present;

- South Africa, 1991-present;

- Hungary, 1997-present;

- India, 1999-present.

Foreign editions of the past:

- England, 1959-1994;

- Denmark, 1962-1971, 1979-1997, 1998-2002;

- The Netherlands, 1964-1996;

- France, 1965, 1992;

- Argentina, 1970-1975;

- Norway, 1971-1972, 1981-1993, 1995, 2002-2003;

- Italy, 1971, 1984, 1992;

- Mexico, 1977-1983, 1984-1986, 1993-1998;

- Carribean, 1977-1983;

- Greece, 1978-1985, 1995-1999;

- Iceland, 1985;

- China, 1990;

- Israel, 1994-1995;

- Turkey, 2000-2003.

Some of the foreign editions have spoofed material that is completely unfamiliar to American audiences, or which is not in keeping with MAD's general avoidance of obscenity (for an example of both, see the Swedish MAD parody of Fucking Åmål [1] (http://membres.lycos.fr/smlfa/vari.html#mad)).

Imitators and variants

Mad30.JPG

MAD has had many imitators through the years. The three most durable of these were Cracked, Sick, and Crazy. Most others were short-lived exercises, such as Zany (4 issues), Frantic (2 issues), Ratfink (1 issue), Nuts! (2 issues), Get Lost (3 issues), Whack (3 issues), Wild (5 issues), Madhouse (8 issues), Riot (6 issues), Flip (2 issues), and Eh! (7 issues). Even MAD's own company, E.C., joined the parade with a sister humor magazine called Panic, which was produced by future MAD editor Al Feldstein. Most of these productions aped MAD's format right down to choosing a synonym for mad as their title. Most also featured a cover mascot along the lines of MAD's Alfred E. Neuman.

In 1967, Marvel Comics produced the first of 13 issues of Not Brand Echh, which parodied their own superhero titles, and owed its entire inspiration and format to the original "MAD" comic books of a decade earlier. From 1973-1976, DC Comics published Plop! which was much the same but relied more on one-page gags and horror-based comedy.

But as it carries on past its 50th year, MAD has outlasted them all, save Cracked, which has appeared infrequently for years but still bobs in and out of production.

Other humor magazines of note include former MAD Editor Harvey Kurtzman's Humbug and Trump, the National Lampoon, and Spy Magazine, but these cannot be considered direct ripoffs of MAD in the same way as the others mentioned here. Of all the competition, only the National Lampoon ever threatened MAD's hegemony as America's top humor magazine, in the early-to-mid-1970s. However, this was also the period of MAD's greatest sales figures. Both magazines peaked in sales about the same time. The Lampoon topped one million sales once, for a single issue in 1974. MAD crossed the 2-million mark with an average 1973 circulation of 2,059,236, then improved to 2,132,655 in 1974.

Gaines reportedly kept a voodoo doll in his business office, into which he would stick pins labelled with each of MAD's imitators. He would only remove a pin when the copycat had ceased publishing. At the time of Gaines' death in 1992, only the pin for Cracked remained.

Some of the Usual Gang of Idiots

Each of the following has created over 150 articles for the magazine:

Writers:

- Dick DeBartolo

- Desmond Devlin

- Stan Hart

- Frank Jacobs

- Tom Koch

- Arnie Kogen

- Jack Rickard

- Larry Siegel

- Mike Snider

Writer-Artists:

- Sergio Aragones

- Dave Berg

- John Caldwell

- Don Edwing

- Al Jaffee

- Don Martin

- Paul Peter Porges

- Antonio Prohias

Artists:

The editorial staff, notably Charlie Kadau, John Ficarra, and Joe Raiola, also have dozens of articles under their own bylines, as well as substantial creative input into many, many others.

Some of the Unusual Gang of Idiots

MAD is known for the stability and of its talent roster, with several creators enjoying 30-, 40-, and even 50-year careers in the magazine's pages. However, about 600 people have received bylines in at least one issue.

Among the contributors to be credited but a single time are Charles Schulz, Richard Nixon, Chevy Chase, Weird Al Yankovic, Donald E. Knuth, Will Eisner, Kevin Smith, J. Fred Muggs, Boris Vallejo, Sir John Tenniel, Jean Shepherd, Winona Ryder, Thomas Nast, Jimmy Kimmel, Jason Alexander, Walt Kelly, Barney Frank, Steve Allen, Jim Lee, Jules Feiffer, and Leonardo da Vinci. Mr. da Vinci's check is still waiting in the MAD offices for him to pick it up.

Contributing just twice are such luminaries as Tom Lehrer, Stan Freberg, Mort Walker, and Gustave Dore. Frank Frazetta (3), Ernie Kovacs (11), Bob and Ray (12), and Sid Caesar (4) are among those to have appeared slightly more frequently. The magazine more commonly used outside "name talent" in its earliest years as a magazine, before amassing its own staff of regulars. More recently, MAD has run occasional "stunt" or "guest" articles in which celebrities from show business or comic books have participated.

The Fundalini Pages

In recent years, MAD has begun its issues with this catch-all section of various bits, which are far shorter or smaller than normal MAD articles. They often appear at as many as 3 to 6 per page. Some of these pieces are produced in-house; others are the work of MAD freelancers, who are credited as "Friends of Fundalini." Among the recurring features in the Fundalini section are:

- Bitterman, a short comic strip by Garth Gerhart about a hateful slacker;

- Celebrity Cause of Death Betting Odds, written by Mike Snider, which ranks the hypothetical future demises of the famous by decreasing likelihood;

- Classified ads; these frequently deal in absurdity and non sequiturs;

- The Cover We DIDN'T Use, purporting to be the second choice for each issue's front cover;

- Foto News, in which topical photographs are given word balloons (similar to fumetti, though usually without the storyline aspect);

- The Godfrey Report, a small 3x 3 grid showing three classes of objects and their current cultural status (arbitrarily rated as "In," "Five Minutes Ago," or "Out.");

- Graphic Novel Review, written by Desmond Devlin, which analyzes fictional comic collections and graphic novels such as "The Anally Complete Peanuts" or "Tintin in Fallujah";

- Magazine Corrections You May Have Missed, providing editorial commentary on other publications;

- Melvin and Jenkins' Guide to..., drawn by Kevin Pope and written by Desmond Devlin, in which the upstanding Jenkins and the derelict Melvin illustrate good and improper behavior in various situations;

- Monkeys Are Always Funny, by Evan Dorkin, showing famous news photographs with the image of a monkey Photoshopped in;

- Pull My Cheney!, a one-panel gag by cartoonist Tom Cheney;

- The Puzzle Nook, a multiple choice fill-in-the-blank phrase;

- Vey to Go!, a one-panel gag by cartoonist P.C. Vey.

"The MAD 20"

Since 1998, MAD has done an annual issue commemorating the "20 Dumbest People, Events and Things" of the year. These frequently favor image over text or content.

MAD named the Reverend Jerry Falwell the "dumbest person of 2001" for blaming the 9/11 attacks on feminists, gays, and lesbians. (Sort of. Though Falwell appeared in the #1 slot in MAD's annual "20 Dumbest People, Events and Things" issue, and the examples are numbered 1-20, the "rankings" are completely random. The "20th dumbest" slot of 2001 was awarded to MAD Magazine itself, for its "slide down the slippery slope of greedy commercialism" in finally permitting advertising in its pages.)

External links

- Official MAD Magazine website (http://www.madmag.com)

- All MAD Magazine covers, and listed contents (http://www.collectmad.com/madcoversite/index-covers.html)

- The magazine's own semi-spurious "Untold History of MAD Magazine" (http://www.dccomics.com/mad/?action=about)

- 50th anniversary poster featuring over 100 "Usual Gang of Idiots" caricatures (http://www.dccomics.com/mad/?action=idiots)

- MAD Magazine lists, including cover artists, most appearances, and circulation figures (http://users.ipfw.edu/slaubau/mad.htm)

- Origins of Alfred E. Neuman (http://www.toonopedia.com/alfred_e.htm)

- MAD Mumblings fan discussion (http://www.madmumblings.com/)

- MAD Magazine Collector Resource Center (http://www.collectmad.com)

- account (http://www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/essays/v12p162y1989.pdf) by Carl Djerassi of encountering Alfred E. Neuman as Nazi racial propaganda.