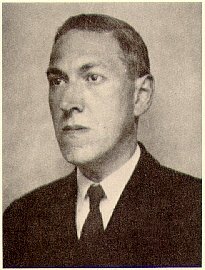

H. P. Lovecraft

|

|

Howard Phillips Lovecraft (August 20, 1890 – March 15, 1937) was an American author of fantasy and horror fiction, noted for giving horror stories a science fiction framework. Lovecraft's readership was limited during his life, but his works have become quite important and influential among writers and fans of horror fiction.

| Contents |

Biography

Lovecraft was born in his family home at 194 (then 454) Angell Street in Providence, Rhode Island. His father was Winfield Scott Lovecraft, a traveling salesman of jewelry and precious metals. His mother was Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft, who could trace her ancestors in America back to their arrival in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. Unusual for the time, both were in their 30s when they married, and it was the first marriage for both. Howard was their only child. When Lovecraft was three his father became acutely psychotic at a hotel in Chicago, where he was on a business trip, and was brought back to Butler Hospital in Providence, where he remained for the rest of his life. His affliction was general paresis.

Lovecraft was thereafter raised by his mother, two aunts (Lillian Delora Phillips and Annie Emeline Phillips), and his grandfather, Whipple Van Buren Phillips, with whom they lived until his death. Lovecraft was something of a prodigy and was reciting poetry at age two and was writing by six. His grandfather encouraged his reading, providing him with classics such as The Arabian Nights, Bulfinch's Age of Fable, and child's versions of The Iliad and The Odyssey. His grandfather also stirred young Howard's interest in the weird by telling him original tales of Gothic horror.

Lovecraft was frequently ill as a child. He attended school only sporadically but he read much. He produced several hectographed publications with a limited circulation beginning in 1899 with The Scientific Gazette.

Whipple Van Buren Phillips died in 1904, and the family was subsequently impoverished by mismanagement of his property and money. The family was forced to move down Angell Street to much smaller and less comfortable accommodations. Lovecraft was deeply affected by the loss of his home and birthplace and even contemplated suicide for a time. He suffered a nervous breakdown in 1908, as a result of which he never received his high school diploma. This failure to complete his education — his hopes of ever entering Brown University dashed — nagged at him for the rest of his life, and he in fact maintained that he was a highschool graduate.

Lovecraft's first polished stories began to appear around 1917 with The Tomb and Dagon. Also around this time he began to build up his huge network of correspondents. His lengthy and frequent missives would make him one of the great letter writers of the century. Among his correspondents were the young Forrest J. Ackerman, Robert Bloch (Psycho) and Robert E. Howard (Conan the Barbarian series).

Lovecraft's mother also was committed to the Butler Hospital, where she died from surgical complications on May 21, 1921.

Shortly after, he attended an amateur journalist convention where he met Sonia Greene. She was Ukrainian, a Jew, and, having been born in 1883, several years older than Lovecraft. They married in 1924, though Lovecraft's aunts were unhappy with the arrangement. The couple moved to the Borough of Brooklyn in New York City. He hated it. A few years later he and Greene agreed to an amicable divorce, and he returned to Providence to live with his aunts during their remaining years. Due to the unhappiness of their marriage, some biographers have speculated that Lovecraft could have been asexual.

The period after his return to Providence — the last decade of his life — was Lovecraft's most prolific. During this time period he produced almost all of his best known short stories for the leading pulp publications of the day (primarily Weird Tales) as well as longer efforts like The Case of Charles Dexter Ward and At the Mountains of Madness. He frequently revised work for other authors and did a large amount of ghost-writing.

Despite his best writing efforts, however, he grew ever poorer. He was forced to move to smaller and meaner lodgings with his surviving aunt. He was also deeply affected by Robert E. Howard's suicide. In 1936 he was diagnosed with cancer of the intestine and he also suffered from malnutrition. He lived in constant pain until his death the following year (1937) in Providence, Rhode Island.

Lovecraft's grave in Swan Point Cemetery in Providence is occasionally marked with graffiti quoting his famous phrase from The Call of Cthulhu (originally from The Nameless City):

- "That is not dead which can eternal lie,

- And with strange aeons even death may die."

Background of Lovecraft's work

Much of Lovecraft's work was directly inspired by his nightmares, and it is perhaps this direct insight into the subconscious and its symbolism that helps to account for their continuing resonance and popularity. All these interests naturally led to his deep affection for the works of Edgar Allan Poe, who heavily influenced his earliest macabre stories and writing style. Lovecraft's discovery of the stories of Lord Dunsany moved his writing in a new direction, resulting in a series of imitative fantasies in a "Dreamlands" setting. It was probably the influence of Arthur Machen, with his carefully constructed tales concerning the survival of ancient evil, and his mystic beliefs in hidden mysteries which lay behind reality, that finally helped inspire Lovecraft to find his own voice from 1923 onwards. This took on a dark tone with the creation of what is today often called the Cthulhu Mythos, a pantheon of alien extra-dimensional deities and horrors which predate mankind, and which are hinted at in aeon-old myths and legends. The term Cthulhu Mythos was coined by Lovecraft's correspondent and fellow author, August Derleth, after Lovecraft's death; Lovecraft referred to his artificial mythology as "Yog-Sothothery"[1] (http://www.sff.net/people/timpratt/611.html). His stories created one of the most influential plot devices in all of horror: the Necronomicon, the secret grimoire written by the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred. The resonance and strength of the Mythos concept have led some to believe that Lovecraft had based it on actual myth, and faux editions of the Necronomicon have also been published over the years.

His prose is somewhat antiquarian. He was fond of heavy use of unfamiliar adjectives such as "eldritch", "rugose", "noisome", "squamous", and "cyclopean", and of attempts to transcribe dialect speech which have been criticized as inaccurate. His works also featured British English (he was an admitted Anglophile), and he sometimes made use of anachronistic spellings, such as "compleat/complete" and "lanthorn/lantern".

Lovecraft was a prolific letter writer, inscribing multiple pages to his group of correspondents in small longhand. He sometimes dated his letters 200 years before the current date, which would have put the writing back in U.S. colonial times, before the American Revolution that offended his Anglophilia. He explained that he thought that the 18th and 20th centuries were the best; the former being a period of noble grace, and the latter a century of science. In his view, the 19th century, particularly the Victorian era, was a "mistake".

Members of Lovecraft's original circle included writers such as Robert Bloch and Frank Belknap Long, who drew influence from and contributed to the Mythos. Many later creators of horror writing and films show influences from Lovecraft, including Clive Barker and H. R. Giger. Others, notably Clark Ashton Smith, August Derleth, Neil Gaiman, Stephen King, Alan Moore, and Brian Lumley, have written stories that are explicitly set in the same "universe" as Lovecraft's original stories. Lovecraft pastiches are common. For more examples of the Mythos in popular culture, see References to the Cthulhu Mythos.

Survey of the work

The definitive editions (specifically At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels, Dagon and Other Macabre Tales, The Dunwich Horror and Others, and The Horror in the Museum and Other Revisions) of his prose fiction are published by Arkham House, a publisher originally started with the intent of publishing the work of Lovecraft, but which has since published a lot of other fantastic literature as well.

Lovecraft's poetry is collected in The Ancient Track: The Complete Poetical Works of H. P. Lovecraft, while much of his juvenilia, various essays on philosophical, political and literary topics, antiquarian travelogues, and other things, can be found in Miscellaneous Writings. Also, Lovecraft's essay Supernatural Horror in Literature, first published in 1927, is a historical survey of horror literature available with endnotes as The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature.

Writing phases

Lovecraft had three very distinct categories of fiction in which he wrote during his life. Although the groups' stories were often written in overlapping time periods with the other groups, there were still periods where almost all of Lovecraft's writings could be categorized in one of the below mentioned groups. It should be noted that these distinctions have been drawn by others and not by Lovecraft himself.

- Macabre stories (approximately 1905–1920)

- Dream-Cycle stories (approximately 1920–1927)

- Cthulhu Mythos stories (approximately 1925–1935)

Letters

Despite the fact that Lovecraft is mostly known for his works of weird fiction, the bulk of Lovecraft's writing mainly consists of voluminous letters about a variety of topics, from weird fiction and art criticism to politics and history. S. T. Joshi estimates that Lovecraft wrote about 87,500 letters from 1912 until his death in 1937 — one famous letter from November 9, 1929 to Woodburn Harris being 70 pages in length.

Lovecraft was not a very active letter-writer in youth. In 1931 he admitted: "In youth I scarcely did any letter-writing - thanking anybody for a present was so much of an ordeal that I would rather have written a two hundred fifty-line pastoral or a twenty-page treatise on the rings of Saturn." (SL 3.369–70). The initial interest in letters stemmed from his correspondence with his cousin Phillips Gamwell but even more important was his involvement in the amateur journalism movement, which was responsible for the enormous number of letters Lovecraft produced.

Lovecraft clearly states that his contact to numerous different people through letter-writing was one of the main factors in broadening his view of the world: "I found myself opened up to dozens of points of view which would otherwise never have occurred to me. My understanding and sympathies were enlarged, and many of my social, political, and economic views were modified as a consequence of increased knowledge." (SL 4.389).

Today there are four publishing houses that have released letters from Lovecraft — Arkham House with its five-volume edition Selected Letters being the most prominent. Other publishers are Hippocampus Press (Letters to Alfred Galpin et al.), Night Shade Books (Mysteries of Time and Spirit: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Donald Wandrei et al.) and Necronomicon Press (Letters to Samuel Loveman and Vincent Starrett et al).

Copyrights

There is no little controversy over the copyright status of many of Lovecraft's works, especially his later works. All works published in the US before 1923 are public domain. However, there is some disagreement over who exactly owns or owned the copyrights and whether the copyrights for the majority of Lovecraft's works published post-1923 - including such prominent pieces as The Call of Cthulhu and The Mountains of Madness - have now expired.

Questions center over whether copyrights for Lovecraft's works were ever renewed under the terms of the USA Copyright Act of 1976 for works created prior to January 1 1978. If Lovecraft's work had been renewed they would be eligible for protection for 75-95 years after the author's death according to the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998. This means the copyrights would not expire on some of Lovecraft's works until 2019 at the earliest, providing that no further laws extend the periods of copyrights within the USA. Similarly, the European Union Directive on harmonising the term of copyright protection of 1993 extended the copyrights to 70 years after the author's death.

In those Berne Convention countries who have implemented only the minimum copyright period, copyright expires 50 years after the author's death.

Lovecraft protégés and part owners of Arkham House, August Derleth and Donald Wandrei often claimed copyrights over Lovecraft's works. On October 9, 1947 Derleth purchased all rights to Weird Tales. However, since April 1926 at the latest, Lovecraft had reserved all second printing rights to stories published in Weird Tales. Hence, Weird Tales may only have owned the rights to at most six of Lovecraft's tales. Again, even if Derleth did obtain the copyrights to Lovecraft's tales no evidence as yet has been found that the copyrights were renewed.[2] (http://phantasmal.sourceforge.net/Innsmouth/LovecraftCopyright.html)

However, prominent Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi concludes in his biography, H.P. Lovecraft: A Life, that Derleth's claims are "almost certainly fictitious" and that most of Lovecraft's works published in the amateur press are most likely now in the public domain. The copyright for Lovecraft's works would have been inherited by the only surviving heir of his 1912 will: Lovecraft's aunt, Annie Gamwell. Gamwell herself perished in 1941 and the copyrights then passed to her remaining descendents, Ethel Phillips Morrish and Edna Lewis. Morrish and Lewis then signed a document, sometimes referred to as the Morrish-Lewis gift, permitting Arkham House to republish Lovecraft's works but retaining the copyrights for themselves. Searches of the Library of Congress have failed to find any evidence that these copyrights were then renewed after the 28 year period and, hence, it is likely that these works are now in the public domain.

According to Peter Ruber's (the current editor of Arkham House) essay, The Un-Demonizing of August Derleth, certain letters obtained in June 1998 detail the Derleth-Wandrai acquisition of Lovecraft's estate. It is unclear whether these letters contradict Joshi's views on Lovecraft's copyrights.[3] (http://www.epberglund.com/RGttCM/nightscapes/NS15/ns15nf01.htm)

It is also worth noting that Chaosium, publishers of the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game, have a trademark on the phrase "The Call of Cthulhu" for use in game products.

Regardless of the legal disagreements surrounding Lovecraft's works, Lovecraft himself was extremely generous with his own works and actively encouraged others to borrow ideas from his stories, particularly with regard to his Cthulhu Mythos. By "wide citation" he hoped to give his works an "air of verisimilitude" and actively encouraged other writers to reference his creations, such as the Necronomicon, Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth. After his death, many writers have contributed stories and enriched the shared mythology of the Cthulhu Mythos, as well as making numerous references to his work (see References to the Cthulhu Mythos).

Racism

Some modern readers have criticised the themes of racism in some of Lovecraft's stories, especially in his early writing. Particularly of note are the two pieces, The Horror at Red Hook and The Street, in which he describes the immigrants of his day as decadent and potentially dangerous. Some of his stories, such as The Shadow over Innsmouth and Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family, might warn against the dangers of miscegenation. Still others, such as Herbert West: Reanimator, contain overtly racist depictions of non-white races and the immigrant population.

Lovecraft's personal correspondence indicates that he did indeed hold racist beliefs. This, however, was regarded as an impolite but probable scientific fact within the anglo-rationalist intellectual framework of the time. However the fact that he married a Jewish Ukrainian woman, Sonia Greene, indicates his changing beliefs from his earlier worldview.

This transformation could be said to mirror the gradual intellectual move away from the Social Darwinism of the early Twentieth Century. Further evidence of his evolution can be found in Shadow Out of Time where he depicts a perfect alien society based, according to some interpretations, on a socialistic system.

A thorough self-written summary of his views on race and culture can be found in the book Selected Letters IV, published by Arkham House, in letter 648 to J. Vernon Shea, written September 25, 1933.

Further reading

In the past few decades, the quantity of books about Lovecraft has increased considerably. Also, Lovecraft's stories themselves have enjoyed a veritable publishing renaissance in recent years. The titles mentioned below are a small sampling.

Lovecraft, a Biography, written by L. Sprague de Camp, published in 1975, and now out of print, was Lovecraft's first full-length biography. Frank Belknap Long's Howard Phillips Lovecraft: Dreamer on the Night Side (Arkham House, 1975) presents a more personal look at Lovecraft's life, combining reminiscence, biography, and literary criticism. Long was a friend and correspondent of Lovecraft, as well as a fellow fantasist who wrote a number of Lovecraft-influenced Cthulhu Mythos stories (including The Hounds of Tindalos). A newer, more extensive biography is H. P. Lovecraft: A Life, written by Lovecraft scholar S. T. Joshi. It was for a long time out of print, but has recently been republished by Necronomicon Press. Used copies are rare. An adequate alternative is Joshi's abridged A Dreamer & A Visionary: H. P. Lovecraft in His Time.

Other significant Lovecraft-related works are An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia (informative but expensive) and Lovecraft's Library: A Catalogue (a meticulous listing of many of the books in Lovecraft's now scattered library), both by Joshi, and also Lovecraft at Last, an account by Willis Conover of his teenage correspondence with Lovecraft. For those interested in studying in detail Lovecraft's writings and philosophy, Joshi's A Subtler Magick: The Writings and Philosophy of H. P. Lovecraft is useful both for the analysis it provides and for the thorough bibliography appended to it. Charles P. Mitchell's The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Filmography is practicable for its discussion of films containing Lovecraftian elements (see Adaptations, below).

Lovecraft's prose fiction has been published numerous times, but, even after the "corrected texts" were released by Arkham House in the 1980s, many non-definitive collections of his stories have appeared, including Ballantine Books editions and, also, three popular Del Rey editions, which nonetheless have interesting introductions. The two collections published by Penguin, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories and The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories, incorporate the modifications made in the corrected texts.

Many readers, when they first encounter Lovecraft's works, find his writing style difficult to read — owing, no doubt, to his fondness for adjectives, long paragraphs, and archaic diction. Also, Lovecraft's early 20th century perspective yielded references in his works to objects and ideas that may be unfamiliar to modern readers. Some of Lovecraft's writings, however, are annotated, meaning that they are accompanied by explanatory footnotes (at the bottom, or foot, of the page) or endnotes (at the end of the book). In addition to the Penguin editions mentioned above and The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature, Joshi has produced The Annotated H. P. Lovecraft as well as More Annotated H. P. Lovecraft, both of which are footnoted extensively.

Lastly, The Philosophy of H. P. Lovecraft presents an excellent and extensive study of Lovecraft's use of language, which further reveals the depth of his writings.

Locations featured in Lovecraft stories

Lovecraft drew extensively from his native New England for settings in his fiction. Numerous real historical locations are mentioned, and several fictional New England locations make frequent appearances.

Historical locations

Fictional locations

- Miskatonic University in the fictional Arkham, Massachusetts

- Innsmouth

- Dunwich

Bibliography

Books

- From Arkham House:

- From Ballantine/Del Rey:

- The Tomb and Other Tales (ISBN 0345336615)

- The Doom That Came to Sarnath (ISBN 0345331052)

- The Lurking Fear and Other Stories (ISBN 0345326040)

- The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath (ISBN 0345337794)

- The Case of Charles Dexter Ward (ISBN 0345354907)

- At the Mountains of Madness and Other Tales of Terror (ISBN 0345329457)

- The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (ISBN 0345350804)

- The Road to Madness (ISBN 0345384229)

- Dreams of Terror and Death: The Dream Cycle of H. P. Lovecraft (ISBN 0345384210)

- Waking Up Screaming: Haunting Tales of Terror (ISBN 034545829X)

- From Night Shade Books:

- From Hippocampus Press:

- The Shadow out of Time Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/shadow_out_of_time.html)

- From the Pest Zone: The New York Stories Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/from_the_pest_zone.html)

- The Annotated Fungi From Yuggoth Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/annotated_fungi_from_yuggoth.html)

- Collected Essays Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/collected_essays_i.html)

- The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/annotated_supernatural_horror_in_literature.html)

- H. P. Lovecraft: Letters to Alfred Galpin Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/letters_to_alfred_galpin.html)

- H. P. Lovecraft: Letters To Rheinhart Kleiner Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/lovecraft_letters_to_rheinhart_kleiner.html)

- Lovecraft's Library: A Catalogue Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/lovecrafts_library.html)

- Primal Sources: Essays on H. P. Lovecraft Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/primal_sources.html)

- An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia Publishers Page (http://www.hippocampuspress.com/lovecraft/h_p_lovecraft_encyclopedia.html)

Adaptations

Films based (generally very loosely) on Lovecraft's works (partial list only; see Lovecraft's IMDB entry (http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0522454/) for a more complete selection):

- The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath (2003), an adaptation of the book by the same name (Official Site (http://www.petting-zoo.org/Movies_Dreamquest.html))

- The Haunted Palace, an adaptation of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward (IMDb entry (http://us.imdb.com/Title?0057128))

- The Resurrected (1992), another adaptation of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0105242/))

- Re-Animator (1985) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0089885/))

- Bride of Re-Animator (1990) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0099180/))

- Beyond Re-Animator (2003) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0222812/))

- From Beyond (1986) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091083/))

- The Dunwich Horror (1970) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0065669/))

- The Unnamable (1988) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/M/title-exact?Unnamable,+The+(1988)))

- The Unnamable II: The Statement of Randolph Carter (1993) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0108447/))

- Dagon (2001), based less on Lovecraft's story of the same name than on The Shadow over Innsmouth (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0264508/))

- The Curse (1987) (an unacknowledged 1980s adaptation of "The Colour Out of Space") (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0092809/))

- Die, Monster, Die! (1965) (another adaptation of "The Colour Out of Space") (IMDb entry (http://imdb.com/title/tt0059465/))

- In the Mouth of Madness (1995) (satirical John Carpenter horror film about the relationship between horror writers and their audience; a Lovecraft pastiche) (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0113409/))

- Necronomicon (1994) Three short films based on his stories (The Rats in the Walls, Cool Air, The Whisperer in Darkness) (IMDb entry (http://imdb.com/title/tt0107664/))

- Hemoglobin aka Bleeders (1997) An unacknowledged adaptation of The Lurking Fear, starring Rutger Hauer. (IMDb entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0119279/))

The 1991 film Cast A Deadly Spell (IMDB entry (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0101550/maindetails)) stars a detective called "Harry Philip Lovecraft", and some elements of the Lovecraftian mythos are mentioned in the movie.

Radio production

- The Call of Cthulhu (Broadcast in Tasmania, on Lovecraft's 100th birthday)

See also

External links

- The H. P. Lovecraft Archive (http://www.hplovecraft.com/)

- "The Ultimate Cthulhu Mythos Book List" (http://lovecraft.cjb.net) - Listing of all mythos novels, anthologies, collections, comic books, and more.

- H. P. Lovecraft and Cthulhu Mythos Information and Forum (http://www.templeofdagon.com/)

- The Cthulhu Lexicon (http://www.netherreal.de/library/lexicon/)

- When the Stars are Right... (Cthulhu Mythos chronology) (http://www.netherreal.de/library/timeline/)

- Essay on Lovecraft by S. T. Joshi (http://www.themodernword.com/scriptorium/lovecraft.html)

- A number of stories by H.P. Lovecraft (http://www.dagonbytes.com/thelibrary/lovecraft/)

- The HP Lovecraft Film Festival (http://www.hplfilmfestival.com/homeflash.htm)

- The HP Lovecraft Historical Society (http://www.cthulhulives.org)

- Library of Bookz - Biblioteka - Horror - H.P. Lovecraft - (Spiral of Life) (http://terror.org.pl/~darkeye/bookz/hor_lovecraft.html)

- Deanimator - Flash game inspired by H.P. Lovecraft (http://artscool.cfa.cmu.edu/~lee/stories/)

- H.P. Lovecraft Ebooks (http://www.rinf.com/e-books/HP-Lovecraft.html)

- Template:Isfdb name

bg:Хауърд Лъвкрафт

da:Howard Phillips Lovecraft

de:H. P. Lovecraft

es:Howard Phillips Lovecraft

eo:H. P. LOVECRAFT

fr:Howard Phillips Lovecraft

ko:하워드 필립스 러브크래프트

it:Howard Phillips Lovecraft

he:הווארד פיליפס לאבקרפט

ja:ハワード・フィリップス・ラヴクラフト

nl:Howard Phillips Lovecraft

pl:Howard Phillips Lovecraftpt:Howard Phillips Lovecraft

ro:H. P. Lovecraft

ru:Лавкрафт, Говард Филлипс

fi:H. P. Lovecraft

sv:H.P. Lovecraft