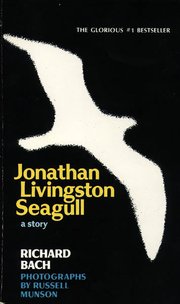

Jonathan Livingston Seagull

|

|

Jonathan Livingston Seagull is a 1970 novel by Richard Bach. It is a fable about a seagull learning about life and flight, and a homily about self-perfection and self-sacrifice. Published as Jonathan Livingston Seagull -- a story, it first became a favourite on American university campuses. By the end of 1972, over a million copies were in print, Reader's Digest had published a condensed version and the book reached the top of the New York Times bestseller list, where it remained for 38 weeks. It is currently still in print.

Jonathan Seagull, the eponymous central character of the story, discovers that he can only be truly happy by being true to himself and his dreams, and by spreading his passion to others. His journey from disappointed seagull to experienced flier to learned teacher forms the central plot of this book.

Plot

This novel tells the story of Jonathan Livingston Seagull, a seagull who is seized by a passion for flight. He pushes himself, learning everything he can about flying, until finally his unwillingness to conform results in his expulsion from his clan. An outcast, he continues to learn, becomes increasingly pleased with his abilities and leads an idyllic life.

He is then met by two seagulls, who take him to a higher plane of existence, where he meets other gulls who love to fly. He discovers that his sheer tenacity and desire to learn make him "a gull in a million", and befriends the wisest gull in that plane, named Chiang. Chiang takes him beyond his previous learning, teaching him how to move instantaneously to anywhere else in the universe. The secret, Chiang says, is to "begin by knowing that you have already arrived."

Not satisfied with his new life, Jonathan returns to Earth to find others like him, to bring them his learning and to spread his love for flight. His mission is successful, gathering around him others who have been outlawed for not conforming. Ultimately, one of his students, Fletcher Lynd Seagull, becomes a teacher in his own right and Jonathan leaves to continue his learning. In some ways, this section is as much a story of Fletcher's realization as of Jonathan's continued learning.

Interpretation

Like any piece of literature, Jonathan Livingston Seagull can be interpreted in many ways. Several early commentators, focusing mainly on the first part of the book, see it as part of the American self-help and positive thinking culture, epitomised by Norman Vincent Peale and by the New Thought movement. Others compare it to the children's tale The Little Engine That Could. But while Jonathan Livingston Seagull may take the form of a traditional animal fable, and can be enjoyed by young children at that level, its attraction has extended beyond this group.

In 1972, before "postmodernism" had not yet evolved from an architectural term rather than a cultural buzzword, Beverley Byrne noted how,

- No matter what metaphysical minority the reader may find seductive, there is something for him in Jonathan Livingston Seagull. ... the dialogue is a mishmash of Boy Scout/Kahlil Gibran. The narrative is poor man's Hermann Hesse; the plot is Horatio Alger doing Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The meanings, metaphysical and other, are a linty overlay of folk tale, old movies, Christian tradition, Protestantism, Christian Science, Greek and Chinese philosophies, and the spirits of Sports Illustrated and Outward Bound ... This seagull is an athletic Siddharta tripping on Similac, spouting the Qur'an as translated by Bob Dylan ... One hopes this is not the parable for our time, popular as it is -- the swift image, all-meaning metaphor that opens up into almost nothing. (Byrne, B 1972. Seagullibility and the American ethos. Pilgrimage. 1:1, pp 59-60.)

One doubts that Byrne would approve, but her analysis has turned out to be almost prophetic. Twenty-first century society, or as much of it as we at its beginning can see emerging, is multicultural, tolerant of cognitive dissonances, constantly seeking new ways of re-appropriating the old. Even our conservatism now carries a multiplicity of meanings.

Today, this multiple layering of meaning, not to mention the ransacking of sources to construct a new playful non-ultimate meaning, is precisely what lends a book appeal. Indeed, there is no longer a single way to look at life, or at a book, and Jonathan Livingston Seagull was, in retrospect, a marker on the road from the 20th to the 21st centuries, from the certainties of modernism to something we call postmodernism -- unless a different name comes along, of course.

One could not claim that it is a deep book in the sense that Crime and Punishment is deep. But it has width, scope, and above all, spirit. It may start off with a paean to progress, but by the end of the book, progress has subsided into no-gress, into the realisation that all is as it must be. It soon escapes from any conceptual framework in which we try to put it. Contrary to Byrne's hopes, it has indeed become the parable for our time. Or at least one of them.

Influenced

The book has inspired the production of a motion picture of the same name (with a soundtrack by Neil Diamond), a ballet, and a popular poster of flying gulls.

The film was made by Hall-Bartlett Productions many years before computer generated effects were available. In order to make seagulls act on cue and perform aerobatics, Mark Smith of Escondido, California built radio-controlled gliders that looked remarkably like real seagulls from a few feet away [1] (http://www.torreypinesgulls.org/Jonathan.htm).he:ג'ונתן ליווינגסטון השחף