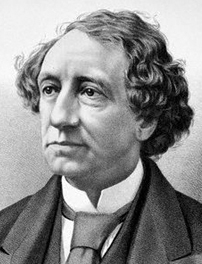

John A. Macdonald

|

|

| |

| Rank: | 1st (1867-1873 and 1878-1891) |

| Date of Birth: | January 11, 1815 |

| Place of Birth: | Glasgow, Scotland |

| Spouses: | Isabella Clark Susan Agnes Bernard |

| Profession: | lawyer |

| Political Party: | Conservative |

The Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, GCB, QC, PC (January 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first Prime Minister of Canada from July 1, 1867 – November 5, 1873 and October 17, 1878 – June 6, 1891. He was born in Glasgow, Scotland.

While there is some debate over his actual birthdate, January 11 is the official date recorded and January 10 is the day Macdonald celebrated it. His parents, Hugh Macdonald and Helen Shaw, met in Scotland in 1811. After the failure of his father's business ventures, his family immigrated to Canada in 1820 along with thousands of others seeking affordable land and promises of new prosperity.

Macdonald did prosper, becoming a lawyer in 1836 and earning the esteem of many in his defence of American raiders in the Rebellions of 1837. In 1843, at the age of 28, he married his cousin, Isabella Clark (1811 - 1857). They had two children: a son John who died at the age of one, and a second son Hugh John who went on to become premier of the Province of Manitoba. Ten years after the passing of his wife, in 1867, the year of Canadian Confederation, he married Susan Agnes Bernard (1836-1920). They had one daughter, Margaret Mary Theodora Macdonald (1869-1933).

| Contents |

Political Rise

In 1843 Macdonald exhibited his first interest in politics. He was elected as alderman of the City of Kingston, Ontario. The next year he accepted the Conservative party's nomination for a seat in the Legislative Assembly of what was then called the Province of Canada but has since been split into the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Winning the seat easily, Macdonald was now a player in the political scene.

He gained the recognition of his peers and in 1847 was appointed Receiver General by William Henry Draper's administration. However, Macdonald lost this distinction when Draper's government lost the next election. He left the Conservatives, hoping to build a more moderate and palatable base, leading to the creation, in 1854, of the Liberal-Conservative Party under the leadership of Sir Allan McNab. Within a few years, the Liberal-Conservatives would attract all of the old Conservative base as well as some centrist Reformers. The Liberal-Conservatives came to power in 1854 and under the new administration Macdonald was appointed Attorney-General. In the next election Macdonald continued his rise in politics by becoming Joint Premier of the Province of Canada with Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché of Québec for the years 1856 and 1857.

In the election of 1858, the Macdonald-Cartier government was defeated and they resigned as Premiers. (Taché had resigned the previous year, with Sir George-Étienne Cartier taking his place). In an interesting piece of politics, the Governor General of Canada asked Cartier to become the senior Premier, only a week after his defeat. Cartier accepted and brought Macdonald into office along with him. This was legal as any member of the cabinet could re-enter the cabinet provided they did so within a month of resigning their previous position. The coalition government was again defeated in 1862. Macdonald then served as the leader of the opposition until the election of 1864, when Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché came out of retirement and joined ranks with Macdonald to form the governing party yet again.

Father of Confederation

At this point in Macdonald's career, he began to look to the future of politics in his region. He was the leader of arguably the largest British colony in the surrounding area and had the power to help enact agreements to confederate the British colonies. This would be done in an attempt to provide stability to the colonies, which were experiencing frequent government changes, to provide the basis for expansion into the West, and to create a unified country in order to guard against attacks from the Americans to the south.

To prevent the frequent changes of government in the Province of Canada, George Brown, the leader of the Reformers (the forerunners to the Liberal Party of Canada) and an extremely vocal opponent of Macdonald's Conservatives, joined with Macdonald in 1864 to form the "Great Coalition." This was an important step towards Confederation. Macdonald then spent 1864 to 1867 organizing the legislation needed to confederate the colonies into the country of Canada. In September 1864, he led the Canadian delegation at the Charlottetown Conference in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, to present his idea to the Maritime colonies, who were discussing a union of their own. In October 1864 delegates for confederation met in Quebec City, Quebec for the Quebec Conference where the Seventy-Two Resolutions were created -- the plan for confederation. By 1866, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Province of Canada had agreed to confederation. Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island were opposed. In the final conference of confederation held in 1866 in London, England the agreement to confederate was completed.

In 1867 the agreement was brought to the British Parliament who passed the British North America Act, creating the Dominion of Canada. Upon the creation of the Dominion of Canada the Province of Canada was then divided into the individual provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

Britain's Queen Victoria knighted John A. Macdonald for playing the integral role in bringing about Confederation. His appointment as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George was announced on the birth of the Dominion, July 1, 1867. An election was held in August which put Macdonald and his Conservative party into power.

Prime Minister

As Prime Minister, Macdonald's vision was to enlarge the country and unify it. Accordingly, under his rule Canada bought Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson's Bay Company for £300,000 (about $11,500,000). This land became the Northwest Territories. In 1870 Parliament passed the Manitoba Act, creating the province of Manitoba out of a portion of the Northwest Territories in response to the Red River Rebellion led by Louis Riel.

In 1871 the British parliament added British Columbia to Confederation, making it the sixth province. Macdonald promised a transcontinental railway connection to persuade the province to join, which his opponents decried as a highly unrealistic and expensive promise. In 1873 Prince Edward Island also joined Confederation, and Macdonald created the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (then named the North-West Mounted Police) to act as a police force for the vast Northwest Territories.

After the Pacific scandal in 1873, in which Macdonald was accused to taking bribes to award contracts for the construction of the railway, the Conservatives were ousted in the 1874 federal election by the Liberal Party of Canada, led by Alexander Mackenzie. Macdonald was re-elected in 1878 on the strength of the National Policy, a plan to promote trade within the country by protecting it from the industries of other nations and renewing the effort to complete the previously promised Canadian Pacific Railway, which was accomplished in 1885. That year, Louis Riel also returned to Canada and launched the North-West Rebellion in the territory of Saskatchewan, but now that there was a railway through the area the North-West Mounted Police were quickly sent to put it down. The trial and subsequent execution of Riel for treason caused a deep political division between French Canadians, who supported Riel (a culturally French Métis) and English Canadians, who supported Macdonald.

Macdonald stayed in office until his death in 1891. His career spanned 19 years, making Sir John A. Macdonald the second longest serving Prime Minister of Canada. He died while still Prime Minister, winning praise for having helped forge a nation of sprawling geographic size, with two diverse European colonial origins, and a multiplicity of cultural backgrounds and political views. Grieving Canadians turned out in the thousands to pay their respects while he lay in state in the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa and they lined the tracks to watch the train that returned his body to Kingston, Ontario where he was buried in the Cataraqui Cemetery.

Macdonald was well known for his wit and also for his alcoholism. He is known to have been drunk for many of his debates in parliament. One famous story is that during an election debate Macdonald was so drunk he began vomiting violently on stage while his opponent was speaking. Picking himself up Macdonald told the crowd, "see how my opponent's ideas disgust me."

In another version of the story, he responded to his opponent's query of his drunkenness with "It goes to show that I would rather have a drunk Conservative than a sober Liberal.".

Sir John A. Macdonald is depicted on the Canadian ten-dollar bill. He also has bridges, airports, and highways named after him (such as the Macdonald-Cartier Freeway), as well as a plethora of schools across the country.

Macdonald and his son, Hugh John Macdonald briefly sat together in the Canadian House of Commons prior to the elder Macdonald's death in 1891. Hugh John later became premier of Manitoba.

In 2004, Sir John A. Macdonald was nominated as one of the top 10 "Greatest Canadians" by viewers of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He is considered by some Canadian political scientists to be the founder of the Red Tory tradition.

External links

- John A. Macdonald, Confederation and Canadian Federalism (http://www2.marianopolis.edu/quebechistory/federal/johna.htm)

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online (http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=40370)

| Preceded by: New position | Prime Minister of Canada 1867-1873 | Succeeded by: Alexander Mackenzie |

| Preceded by: Alexander Mackenzie | Prime Minister of Canada 1878-1891 | Succeeded by: John Abbott |

| Preceded by: none | Conservative Leader | Succeeded by: John Abbott Template:Wikiquotede:John Macdonald fr:John A. Macdonald pl:John Macdonald pt:John Alexander Macdonald |