History of Sudan

|

|

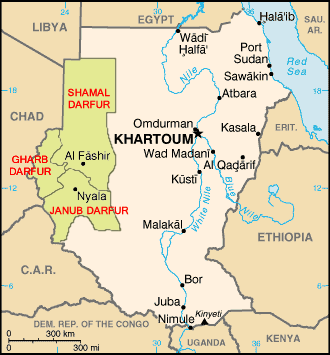

The history of Sudan is marked by influences (military and cultural) from neighboring areas (e.g. Egypt, Arabian Peninsula, Ethiopia, Congo, Chad) and world powers (e.g. United Kingdom, United States).

| Contents |

Early history

During the ancient period, the area that today is northern Sudan was known as Nubia. Egyptians and other peoples of the Mediterranean world also referred to it as Ethiopia (see History of Ethiopia). The area of the Nile valley that lies within present day Sudan was home to three Kushite kingdoms during antiquity: the first with its capital at Kerma (2400 – 1500 BCE), another that centered on Napata (1000 – 300 BCE) and, finally, that of MeroŽ (300 BCE – 300 CE).

Each of these kingdoms was strongly culturally, economically, politically and militarily influenced by the powerful pharaonic Egyptian empire to the north — and the Kushite kingdoms in turn competed strongly with Egypt, to the extent that during the late period of ancient Egyptian history the kings of Napata conquered and unified Egypt itself, ruling as the pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. One of the more notable ones was Taharqa, who was involved in war with the advancing Assyrians. During the period the Nubian pyramids were built.

The Meroitic Empire disappeared by the fourth century AD. By the sixth century a group of three Christian states had arisen in Nubia. The northernmost of these was Nobatia, south of the First Cataract of the Nile. Makuria was situated at Old Dongola, and the kingdom of Alodia was around Soba on the Blue Nile. Nobatia eventually merged into Makuria leaving two kingdoms.

Islam came to Egypt in the 640s, and pressed southward; around 651 the governor of Egypt raided as far south as Dongola. The Egyptians met with stiff resistance and found little wealth worth capturing. They thus ceased their offensive and a treaty was signed between the Arabs and Makuria known as the baqt. This treaty held for some seven hundred years. The area between the Nile and the Red Sea was a source of gold and emeralds, and Arab miners gradually moved in. Around the 970s an Egyptian envoy Ibn Sulaym went to Dongola and wrote an account afterwards; it is now our most important source for this period. Despite the baqt northern Sudan became steadily Islamicized and Arabized; Makuria collapsed in the fourteenth century with Alodia disappearing somewhat later.

Far less is known about the history of southern Sudan. It seems as though it was home to a variety of semi-nomadic tribes. In the 16th century one of these tribes, known as the Funj, moved north and united Nubia forming the Kingdom of Sennar. The Funj sultans quickly converted to Islam and that religion steadily became more entrenched. At the same time, the Dar Fur Sultanate arose in the west. Between them, the Taqali established a state in the Nuba Hills.

The economy of Sudan was feudally based, with a large number of slaves supporting the ruling Jellaba class. The Jellaba were Arab merchants who had come to Sudan with Islam. They traded across the region, but did not build up much industrial or productive capability in Sudan. [1] (http://www.sas.upenn.edu/African_Studies/Articles_Gen/cvlw_env_sdn.html) Through the centuries millions of slaves were captured and sold in Sudan, many being exported to the Middle East and eventually the Americas. The slave trade made southern blacks hostile toward Islam, preventing its spread in those areas.

19th Century

In 1820 - 21, an Egyptian-Ottoman force conquered and unified the northern portion of the country. They were looking to open new markets and sources of natural resources. Historically, the pestilential swamps of the Suud discouraged expansion into the deeper south of the country. Although Egypt claimed all of the present Sudan during most of the 19th century, and established a province Equatoria in southern Sudan to further this aim, it was unable to establish effective control over the area, which remained an area of fragmented tribes subject to frequent attacks by slave raiders.

During the 1870s European initiatives against the slave trade caused an economic crisis in southern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces.

Mahdism and condominium

In 1881, a religious leader named Muhammad ibn Abdalla proclaimed himself the Mahdi, or the “expected one,” and began a religious crusade to unify the tribes in western and central Sudan. His followers took on the name “Ansars” (the followers) which they continue to use today and are associated with the single largest political grouping, the Umma Party, led by the descendant of the Mahdi, Sadiq al Mahdi. Taking advantage of conditions resulting from Ottoman-Egyptian exploitation and maladministration, the Mahdi led a nationalist revolt culminating in the fall of Khartoum in 1885, where the British General Charles George Gordon was killed. The Mahdi died shortly thereafter, but his state survived until overwhelmed by an Anglo-Egyptian force under Lord Kitchener in 1898. Sudan was proclaimed a condominium in 1899 under British-Egyptian administration. The Governor-General of the Sudan, for example, was appointed by 'Khedival Decree', rather than simply by the British Crown, but while maintaining the appearance of joint administration, the British Empire formulated policies, and supplied most of the top administrators.

See also : Battle of Omdurman, Battle of Umm Diwaykarat

European Colonialism

In 1892 a Belgian expedition claimed portions of southern Sudan that became known as the Lado Enclave. The Lado Enclave was officially part of the Belgian Congo. An 1896 agreement between Britain and Belgium saw the enclave turned over to the British after the death of King Leopold II in 1910.

At the same time the French claimed several areas: Bahr el Ghazal, and the Western Upper Nile up to Fashoda. By 1896 they had a firm administrative hold on these areas and they planned on annexing them to French West Africa. An international conflict known as the Fashoda incident developed between France and Britain over these areas. In 1899 France agreed to cede the area to Britain.

From 1898 Britain and Egypt administered all of present day Sudan, but northern and southern Sudan were administered as separate colonies. In the very early 1920s the British passed the Closed Districts Ordinances which stipulated that passports were required for travel between the two zones, permits were required to conduct business in the other zone, and totally separate administrations.

In the south, English, Dinka, Bari, Nuer, Latuko, Shilluk and Azande were official languages, while in the north Arabic and English were used as official languages. Islam was discouraged in the south, where Christian missionaries were permitted to work. Colonial governors of south Sudan attended colonial conferences in East Africa, not Khartoum, and the British hoped to add south Sudan to their East African colonies.

Most of the British focus was on developing the economy and infrastructure of the north. Southern political arrangements were left largely as they had been prior to the arrival of the British. Until the 1920s the British had very little authority in the south anyway.

In order to establish their authority in the north, the British promoted the power of Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani, head of the Khatmiyya sect and Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, head of the Ansar sect. The Ansar sect essentially became the Umma party, and Khatmiyya became the Democratic Unionist Party.

In 1943 the British began preparing the north for self-rule, establishing a North Sudan Advisory Council to advise on the governance of the six North Sudan provinces: comprising of Khartoum, Kordofan, Darfur, and Eastern, Northern and Blue Nile provinces.

Then in 1946 the British colonial authority reversed its policy and decided to integrate north and south Sudan under one government. South Sudanese authorities were informed at the Juba conference of 1947 that they would now be governed by a common administrative authority with the north. From 1948, 13 delegates, picked by the British authorities represented the south on the Sudan Legislative Assembly.

Many southerners felt betrayed by the British because they were largely excluded from the new government. The language of the new government was Arabic, but the bureaucrats and politicians from southern Sudan had, for the most part, been trained in English. Of the 800 new governmental positions vacated by the British in 1953, only 4 were given to southerners.

Also, the political structure in the south was not as organized in the north, so political groupings and parties from the south were not represented at the various conferences and talks that established the modern state of Sudan. As a result, many southerners do not consider Sudan to be a legitimate state.

Independence and the First Civil War

See main article: First Sudanese Civil War

In February 1953, the United Kingdom and Egypt concluded an agreement providing for Sudanese self-government and self-determination. The transitional period toward independence began with the inauguration of the first parliament in 1954. With the consent of the British and Egyptian Governments, Sudan achieved independence on 1 January, 1956, under a provisional constitution. The United States was among the first foreign powers to recognize the new state. However, the Arab-led Khartoum government reneged on promises to southerners to create a federal system, which led to a mutiny by southern army officers that sparked 17 years of civil war (1955-1972). In the early period of the war, hundreds of northern bureaucrats, teachers, and other officials, serving in the south were massacred.

The National Unionist Party (NUP), under Prime Minister Ismail al-Azhari, dominated the first cabinet, which was soon replaced by a coalition of conservative political forces. In 1958, following a period of economic difficulties and political maneuvering that paralyzed public administration, Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Ibrahim Abboud overthrew the parliamentary regime in a bloodless coup.

Gen. Abboud did not carry out his promises to return Sudan to civilian government, however, and popular resentment against army rule led to a wave of riots and strikes in late October 1964 that forced the military to relinquish power.

The Abboud regime was followed by a provisional government until parliamentary elections in April 1965 led to a coalition government of the Umma and National Unionist Parties under Prime Minister Muhammad Ahmad Mahjoub. Between 1966 and 1969, Sudan had a series of governments that proved unable either to agree on a permanent constitution or to cope with problems of factionalism, economic stagnation, and ethnic dissidence. The succession of early post-independence governments were dominated by Arab Muslims who viewed Sudan as a Muslim Arab state. Indeed, the Umma/NUP proposed 1968 constitution was arguably Sudan’s first Islamic-oriented constitution.

Dissatisfaction culminated in a second military coup on 25 May 1969. The coup leader, Col. Gaafar Nimeiry, became prime minister, and the new regime abolished parliament and outlawed all political parties.

Disputes between Marxist and non-Marxist elements within the ruling military coalition resulted in a briefly successful coup in July 1971, led by the Sudanese Communist Party. Several days later, anti-communist military elements restored Nimeiry to power.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement led to a cessation of the north-south civil war and a degree of self-rule. This led to ten years hiatus in the civil war.

Until the early 1970s Sudan's agricultural output was mostly dedicated to internal consumption. In 1972 the Sudanese government became more pro-Western, and made plans to export food and cash crops. However, commodity prices declined throughout the 1970s causing economic problems for Sudan. At the same time, debt servicing costs, from the money spent mechanizing agriculture, rose. In 1978 the IMF negotiated a Structural Adjustment Program with the government. This further promoted the mechanized export agriculture sector. This caused great economic problems for the pastoralists of Sudan.

In 1976, the Ansars mounted a bloody but unsuccessful coup attempt. In July 1977, President Nimeiry met with Ansar leader Sadiq al-Mahdi, opening the way for reconciliation. Hundreds of political prisoners were released, and in August a general amnesty was announced for all opponents of Nimeiry’s government.

Arms Suppliers

Sudan relied on a variety of countries for its arms supplies. After independence the army had been trained and supplied by the British, but after the 1967 Six-Day_War relations were cut off. At this time relations with the USA and West Germany were also cut off.

From 1968-1972 the Soviet Union and eastern block nations sold large numbers of weapons and provided technical assistance and training to Sudan. At this time the army grew from a strength of 18,000 to roughly 50,000 men. Large numbers of tanks, aircraft, and artillery were acquired at this time, and they dominated the army until the late 1980s.

Relations cooled between the two sides after the coup in 1972, and the Khartoum government sought to diversify its suppliers. The USSR continued to supply weapons until 1977, when their support of marxist elements in Ethiopia angered the Sudanese sufficiently to cancel their deals. China was the main supplier in the late 1970s.

Egypt was the most important military partner in the 1970s, providing missiles, personnel carriers, and other military hardware. At the same time military cooperation between the two countries was important.

Western countries began supplying Sudan again in the mid 1970s. The United States began selling Sudan a great deal of equipment around 1976, hoping to counteract Soviet support of marxist Ethiopians and Libyans. Military sales peaked in 1982 at US$101 million. After the start of the second civil war, American assistance dropped, and was eventually all but cancelled in 1987. [2] (http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-13451.html)

Second Civil War

Main article: Second Sudanese Civil War

In 1983 the civil war was reignited following the government's islamicization policy which would have instituted shari'a law, among other things. After several years of fighting, the government compromised with southern groups. In 1989 it appeared the war would end, but a coup brought a military junta into power which was not interested in compromise. Since that time the war has raged across Sudan.

The ongoing civil war has displaced more than 4 million southerners. Some fled into southern cities, such as Juba; others trekked as far north as Khartoum and even into Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Egypt, and other neighboring countries. These people were unable to grow food or earn money to feed themselves, and malnutrition and starvation became widespread. The lack of investment in the south resulted as well in what international humanitarian organizations call a “lost generation” who lack educational opportunities, access to basic health care services, and little prospects for productive employment in the small and weak economies of the south or the north.

Peace talks between the southern rebels and the government made substantial progress in 2003 and early 2004, although skirmishes in parts of the south have reportedly continued. The two sides have agreed that, following a final peace treaty, southern Sudan will enjoy autonomy for six years, and after the expiration of that period, the people of southern Sudan will be able to vote in a referendum on independence. Furthermore, oil revenues will be divided equally between the government and rebels during the six-year interim period. The ability or willingness of the government to fulfull these promises has been questioned by some observers, however, and the status of three central and eastern provinces remains a point of contention in the negotiations.

Darfur

Main article: Darfur conflict

A new rebellion in the western region of Darfur began in early 2003. The rebels accuse the central government of neglecting the Darfur region, although the two rebel groups fighting there appear to be divided on the question of whether to seek secession from the Sudan or the overthrow of the government in Khartoum. Both the government and the rebels have been accused of atrocities in this war, although most of the blame has fallen on Arab militias allied with the government. The rebels have alleged that these militias have been engaging in ethnic cleansing in Darfur, and the fighting has displaced hundreds of thousands of people, many of them seeking refuge in neighboring Chad. In February 2004, the government declared victory over the rebellion shortly after capturing Tine, a town on the border with Chad, but the rebels say they remain in control of rural areas and reports indicate that widespread fighting continues.

References

- Photographs from the Sudan (http://www.ryanspencerreed.com/main.html)

- P.M. Holt and M.W. Daly, A History of the Sudan (1961, 5th ed. Longman 2000)

- South Sudan: A History of Political Domination - A Case of Self-Determination, (Riek Machar) (http://www.sas.upenn.edu/African_Studies/Hornet/sd_machar.html)

- Civil War in Sudan: The Impact of Ecological Degradation (http://www.sas.upenn.edu/African_Studies/Articles_Gen/cvlw_env_sdn.html)

- Multimedia Presentation on Darfur (http://www.detroitfocus.org/Issues/0410/CryForCompassion/index.html)

- Sudan Emancipation & Preservation Network (SEPNet) (http://www.sepnet.org)de:Geschichte Sudans