History of Crete

|

|

| Contents |

Prehistoric Crete

Little is known about the rise of ancient Cretan society, because very few written records remain. This contrasts with the superb palaces, houses, roads, paintings and sculptures that do remain.

Cretan history is surrounded by legends (such as those of King Minos; Theseus and the Minotaur; and Daedalus and Icarus) that have been passed to us via Greek historian/poets (such as Homer).

Because of a lack of written records, estimates of Cretan chronology are based on well-established Aegean and Ancient Near Eastern pottery styles, so that Cretan timelines have been made by seeking Cretan artefacts traded with other civilisations (such as the Egyptians) - a well established occurrence. For the earlier times, radiocarbon dating of organic remains and charcoal offers independent dates. Based on this, it is thought that Crete was inhabited from the 7th millennium BCE onwards. The fall of Knossos took place circa 1400 BC. Subsequently Crete was controlled by the Mycenaeans from mainland Greece.

The first human settlement in Crete dates to the aceramic Neolithic. There have been some claims for Palaeolithic remains, none of them very convincing. The finds from Samaria-gorge, idenitfied as Mesolithic by some scholars, seem to be the product of trampling. The native fauna of Crete included pygmy hippo, pygmy elephant, dwarf deer (Praemegaceros cretensis), giant rodents and insectivores as well as badger, beech marten and a kind of terrestrial otter. Large carnivores were lacking. Most of these animals died out at the end of the last ice-age. It is still not sure if man played a part in this extinction, which is found on other big and medium size Mediterranean islands as well, for example on Cyprus, Sicily and Majorca Up to now, no bones of the endemic fauna have been identified in Neolithic settlements.

Remains of a settlement found under the Bronze Age palace at Knossos (layer X) date to the 7th Millennium BC cal.

| Date BP | SDR | Lab-Number |

|---|---|---|

| 8050 | 180 | BM-124 |

| 7910 | 140 | BM-278 |

| 7740 | 140 | BM-436 |

The first settlers introduced cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and dogs, as well as domesticated cereals and legumes.

Up to now, Knossos remains the only aceramic site. The settlement covered approximately 350,000 square metres. The sparse animal bones contain the above-mentioned domestic species as well as deer, badger, marten and mouse: the extinction of the local megafauna had not left much game behind.

The pottery Neolithic is known from Knossos, Lera Cave and Gerani Cave. The Late Neolithic sees as proliferation of sites, pointing to a population increase. In the late Neolithic, the donkey and the rabbit were introduced to the island, deer and agrimi hunted. The agrimi, a feral goat, preserves traits of the early domesticates. Horse, fallow deer and hedgehog are only attested from Minoan times onwards.

See Minoan civilization for more detail.

Minoan-Mycenaean Crete

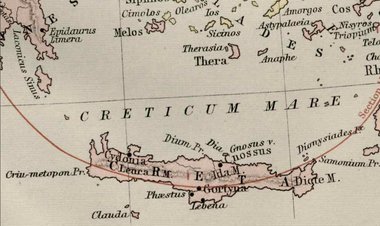

Crete was occupied down to the 15th century BCE by people who did not speak Greek, for evidence of their written language (Linear A) survives, and though it has not been deciphered, it is not Greek. Tablets inscribed in Linear A have been found in numerous sites in Crete, and a few in the Aegean islands. The Cretans (we call them Minoans) established themselves in many islands besides Crete: secure identifications of Minoan off-island sites include Kea, Kythera, Milos, Rhodes, and above all, Thera (Santorini), the site about which most is known.

Archaeologists ever since Sir Arthur Evans have identified and uncovered the palace-complex at Knossos, the most famous Minoan site. Other palace sites in Crete such as Phaistos have uncovered magnificent stone-built, multi-story palaces containing drainage systems, and the queen had a bath and a flushing toilet. The expertise displayed in the hydraulic engineering was of a very high level. There were no defensive walls to the complexes. By the 16th century BCE pottery and other remains on the Greek mainland show that the so-called Minoans had far-reaching contacts on the mainland. In the 16th century a major earthquake caused destruction on Crete and on Thera that was swiftly repaired.

But about 1500 BCE a massive volcanic explosion blew the island of Thera apart, casting more than four times the amount of ejecta as the explosion of Krakatoa and generating a tsunami in the enclosed Aegean that threw pumice up to 250 meters above sea level on the slopes of Anaphi, 27 km to the east. Any fleet along the north shore of Crete was destroyed and John Chadwick suggests that the hegemony of Cretan fleets had kept the island secure from the Greek-speaking mainlanders. The catastrophe that overtook the Cretan palaces seems to have come about 1450 BCE, when all the sites save Knossos were destroyed by fires.

Mycenaeans from the mainland took over Knossos, rebuilding some parts to suit them. A new writing system Linear B, came out of this civilization and show us that Cretans of this time now spoke a dialect of Greek.

Classical, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Crete

In the Classical and Hellenistic period Crete fell into a pattern of combative city-states, harboring pirates. Gortyn, Kydonia (Chania) and Lyttos challenged the primacy of ancient Knossos, preyed upon one another, invited into their feuds mainland powers like Macedonia and its rivals Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt, a situation that all but invited Roman interference. Ierapytna (Ierapetra) gained supremacy on eastern Crete.

In 88 BC Mithridates VI of Pontus on the Black Sea, went to war to halt the advance of Roman hegemony in the Aegean. On the pretext that Knossos was backing Mithradates, Marcus Antonius Creticus attacked Crete in 71 BCE and was repelled. Rome sent Quintus Caecilius Metellus with three legions to the island. After a ferocious three-year campaign Crete was conquered for Rome in 69 BCE, earning this Metellus the agnomen "Creticus." At the archaological sites, there seems to be little evidence of widespread damage associated with the transfer to Roman power: a single palatial house complex seems to have been razed. Gortyn seems to have been pro-Roman and was rewarded by being made the capital of a province that at times joined Cyrenaica to Crete.

Gortyn was the site of the largest Christian basilica on Crete, the Basilica of Ayios Titos dedicated to Saint Titus, the first Christian bishop in Crete, to whom Paul addressed one of his epistles. The church was begun in the 5th century.

Crete continued to be part of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine empire, a quiet cultural backwater, until it fell into the hands of the Arabs in 824. The archbishop of Gortyn (Cyril) was assassinated and the city so thoroughly devastated it was never reoccupied. Candia (Heraklion), a city built by the Arabs, was made capital of the island instead.

In the 10th century Nicephorus Phocas reconquered Crete for the Byzantines, who held it until 1204, when it fell into the hands of the Venetians at the time of the Fourth Crusade. The Venetians retained the island until 1669, when the Ottoman Turks took possession of it.

(The standard survey for this period is I.F. Sanders, An archaeological survey and Gazetteer of Late Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine Crete, 1982)

- Annette Bingham, "Crete's Roman past: excavations yield antiquities from the Roman period," History Today, November 1995 (http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1373/is_n11_v45)

Venetian and Ottoman Crete

In the partition of the Byzantine empire after the capture of Constantinople by the Latins in 1204, Crete was eventually acquired by Venice which held it for more than four centuries. During Venetian rule, the Greek population of Crete was exposed to Italian Rennaissance culture. A thriving literature in the colloquial Cretan dialect of Greek developed on the island. The most known work from this period is the poem Erotokritos by Vinzencos Cornaros. Domenicos Theotocopoulos, better known as El Greco, was born in Crete in this period and was trained in Byzantine iconography before moving to Italy and later, Spain.

During the 17th century Venice was pushed out of Crete by the Ottoman Empire, with most of the island lost after a siege lasting from 1648 to 1669 (the fall of Candia). This is possibly the longest siege in history. The last Venetian outposts on the island were lost in 1718, and Crete was a part of the Ottoman Empire for the next two centuries. There were significant rebellions against Ottoman rule, particularly in Sfakia. Daskalogiannis was a famous rebel leader.

The Greek War of Independence began in 1821 and Cretan participation was extensive. The Turks responded by seeking the aid of the Pasha of Egypt, and brutal campaigns crushed the island's resistance. In 1832 a Greek state was established which, however, did not include Crete and the island passed to the Egyptians, in acknowledgement of their assistance. In 1840, Egypt returned Crete to the Ottoman sultan.

Modern Crete

After Greece achieved its independence, Crete became an object of contention as its Greek populations revolted twice against Ottoman rule (in 1866 and 1897). Ethnic tension prevailed on the island between the Muslim ruling minority and the Christian majority. Aided by volunteers and reinforcements from Greece, the "Great Cretan Revolution" began in 1866 and the rebels scored a series of victories. However, as more Turkish forces landed on the island, reprisals, usually against non-combatants, became common, and the revolt was crushed by 1869. The siege and subsequent explosion of the monastery at Arkadi in 1866 was a famous episode in this revolution.

A new Cretan insurrection in 1897 led to Turkey declaring war on Greece and defeating it. However, the Great Powers (Britain, France, Italy and Russia) decided that Turkey could no longer maintain control and intervened. Turkish forces were expelled in 1898, and an independent Cretan Republic, headed by Prince George of Greece, was founded. Taking advantage of domestic turmoil in Turkey in 1908, the Cretan deputies declared union with Greece. But this act was not internationally recognized until 1913 after the Balkan Wars. Under the Treaty of London, Sultan Mehmed V relinquished his formal rights to the island. In December, the Greek flag was raised at the Firkas fortress in Chania, with Venizelos and King Constantine in attendance, and Crete was unified with mainland Greece. The Muslim minority of Crete initially remained in the island but was later relocated to the Turkey under the general population exchange agreed in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne between Turkey and Greece.

In World War II, Crete provided the setting for the Battle of Crete (May 1941), wherein German invaders, especially paratroops, drove out a British Empire force commanded by General Sir Bernard Freyberg.