History of Chinese immigration to Canada

|

|

This is the history of Chinese immigration to Canada.

| Contents |

Early history

While the first Chinese in British North America (the area that has become Canada) could be traced back in 1788, the first major wave of Chinese immigration started after the Opium War. Most of this first group came from the Taishan County of Guangdong Province to escape from poverty and political instability during the mid-19th century. Most of those rural Cantonese made their way into Canada via the crown colony of Hong Kong.

Chinese appeared in large numbers in the colony of British Columbia in 1858, when there was a gold rush in the Fraser Valley. This attracted many Chinese from China itself, and also some who had originally arrived in California. It should be noted that the Chinese who came to Canada had a different mindset from that of their European counterparts. While most of the European settlers planned to start a new life in the new land, the Chinese in Canada were merely sojourners who wished to return to their ancestral homeland back in China.

Immigration in the mid-19th century

Chinese railway workers made a significant contribution to the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway in British Columbia. When British Columbia agreed to join Confederation in 1871, one of the conditions was that the Dominion government build a railway linking B.C. with eastern Canada within 10 years. Canada's first Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, wanted to cut costs by employing Chinese to build the railway, and famously said, "No Chinese, no railway." (More precisely: "Either you must have this labour, or you cannot have the railway.")

In 1880, Andrew Onderdonk, the Canadian Pacific Railway construction contractor in British Columbia, signed several agreements with Chinese gangs in China's Guangdong province. Through those contracts more than 5000 labourers were sent from China by ship. Onderdonk also recruited over 7000 Chinese railway workers from California. These two groups of workers were the main force for the building of the railway. Many of them fell ill during construction or died while planting explosives. Many others were injured or died because of construction accidents. By the end of 1881, the first group of Chinese labourers, which was previously numbered at 5000, had less than 1500 remaining. Onderdonk needed more workers, so he directly contracted some large Chinese firms to send many more workers to Canada.

Most of the Chinese workers lived in tents. These canvas tents were often unsafe, and rocks fell during the night. Onderdonk paid Chinese workers only $1 a day while white workers were paid five or six times that amount. Even though Chinese railway workers were only responsible for 500 kilometres of the entire Canadian Pacific Railway, they were given the most dangerous section of the railway, notably the section that goes through the Fraser Canyon.

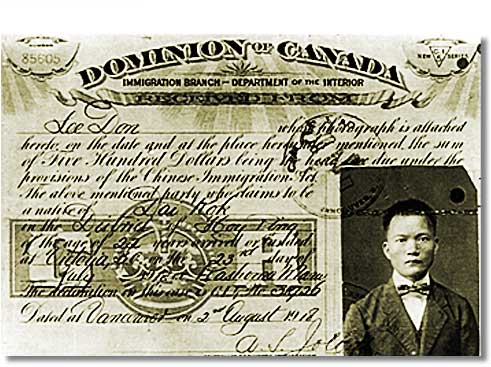

Chinese in Canada after the completion of the CPR

Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885, Canada no longer needed Chinese labourers. As a result, the government of Canada passed a law in 1885 levying a "head tax" of $50 on any Chinese coming to Canada. After the 1885 legislation failed to deter Chinese immigration to Canada, the government of Canada passed another law in 1900 to increase the tax to $100, and in 1904 it was increased (landing fees) to $500 (equivalent to $8000 in 2003). The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, better known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, banned Chinese immigration to Canada with the exceptions of merchants, diplomats, students, and "special circumstances". The Chinese that entered Canada before 1923 had to register with the local authorities and could leave Canada only for two years or less. Because the Exclusion Act went into effect on July 1, 1923, the Chinese at the time referred to Dominion Day as "Humiliation Day" and refused to celebrate Dominion Day until the act was repealed.

From the completion of the CPR to the end of the Exclusion Era (1923-1947), MUSHONE Chinese in Canada lived in mainly a "bachelor's society" since many Chinese families would not pay the expensive head tax to send their daughters to Canada. Also, since most Chinese in Canada could speak only pidgin English, they had to hide in the "Chinatown ghettos". With resentment of Chinese growing in British Columbia, Chinese settlers began moving eastward after the completion of the CPR. With legislation banning Chinese from many professions, Chinese entered professions that European Canadians did not want to do, like laundry shops or salmon processing. The Chinese also opened grocery stores and restaurants that catered to the local Chinese population.

After legislation in 1896 that stripped Chinese voting rights in municipal elections in B.C., the Chinese in B.C. became completely disenfranchised. The electors list in federal elections came from the provincial electors list, and the provincial ones came from the municipal one. As a way to counter the racist environment, Chinese merchants began forming the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, with the first branch in Victoria in 1885 and the second one in Vancouver in 1895. The Association was mandatory for all Chinese in the area to join, and it did everything from representing members in legal disputes to sending the remains of a members who died back to their ancestral homelands in China.

After Canada entered World War II on September 10, 1939, Chinese communities greatly contributed to Canada's war effort, mainly in an attempt to persuade Canada to intervene against Japan in the Sino-Japanese War, which had started in 1937. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association requested its members to purchase Canadian and Chinese war bonds and to boycott Japanese goods. Also, many Chinese enlisted in the Canadian forces. But Ottawa and the B.C. government were unwilling to send Chinese-Canadian recruits into action, since they did not want Chinese to ask for enfranchisement after the war. However, with 100,000 British troops captured in British Malaya in February 1942, Ottawa decided to send Chinese-Canadian forces in as spies to train the local guerrillas to resist the Japanese Imperial Forces in 1944. However, these spies did not make much of a difference, as the outcome of World War II was more or less decided by that time.

Chinese in post-war Canada

The experiences of the Holocaust made racial discrimination unacceptable in Canada, at least from the government policy standpoint. Also, with the war aim of defeating Nazism in terms of discrimination, Canada's racial legislation made it look hypocritical. Moreover, with Chinese-Canadian contributions in World War II, and also because some of the anti-Chinese legislation violated the UN Charter, the government of Canada repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act and gave Chinese Canadians full citizenship rights in 1947. However, Chinese immigration was limited only to the spouse of a Chinese who had Canadian citizenship and his dependents. However, after the founding of the People's Republic of China in October 1949 and its support for the communist North in the Korean War, Chinese in Canada faced another wave of resentment, as Chinese were viewed as communist agents from the PRC (although most Chinese-Canadians at the time were strongly pro-Nationalist).

In 1959, the Department of Immigration discovered an abuse of immigration papers by some Chinese immigrants; the Royal Canadian Mounted Police were brought in to investigate. It turned out that some Chinese had been entering Canada by purchasing real or fake birth certificates of Chinese Canadian children bought and sold in Hong Kong. These children carrying false identity papers were referred to as "paper sons". In response, Douglas Jung (the first Chinese MP in Canadian history) introduced a private member's bill in 1962 called the Chinese Adjustment Program. The bill granted amnesty for paper sons or daughters if they confessed to the government. As a result about 12,000 paper sons came forward, until the amnesty period ended in October 1973.

Independent Chinese immigration in Canada came after Canada eliminated race and the "place of origin" section from its immigration policy in 1967. From 1947 to the early 1970s, Chinese immigrants from Canada came from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. Chinese from the mainland who were eligible in the family reunification program had to visit the Canadian High Commission in Hong Kong, since Canada and the PRC did not have diplomatic relations until 1970.

Institutional racism was completely eliminated in 1971 with the implementation of the multicultural policy. After the implementation of the policy, Chinese finally felt that they were welcomed into the mainstream of Canadian society. With the political uncertainties as Hong Kong headed towards 1997, many residents of Hong Kong chose to emigrate to Canada. It was easy for them to enter Canada due to their British Commonwealth connections. According to statistics compiled by the Canadian Consulate in Hong Kong, from 1991 to 1996, "about 30,000 Hong Kongers emigrated annually to Canada, comprising over half of all Hong Kong emigration and about 20 percent of the total number of immigrants to Canada."

Today, mainland China has taken over from Hong Kong and Taiwan as the biggest source of ethnic Chinese immigration. The PRC has also taken over from all countries and regions as the country sending the most immigrants to Canada. According to the 2002 statistics from the Department of Citizenship and Immigration, the PRC has supplied the biggest number of Canadian immigrants since 2000, averaging well over 30,000 immigrants per year, totalling an average of 15% of all immigrants to Canada.

See also

External links

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship (http://www.cic.gc.ca/)

- Canadian Government in China (http://www.beijing.gc.ca/)

- Chinese Canadian National Council (http://www.ccnc.ca/)zh: 加拿大華人歷史